Within the bustling arteries of any major metropolis, an extraordinary, often overlooked narrative of deep time unfolds, etched into the very fabric of its architecture. This profound geological history, spanning billions of years, is not confined to remote wildernesses but is perpetually on display in the stone facades, polished floors, and sturdy foundations of our urban environments. In cities like Seattle, this journey into Earth’s primordial past begins at street level, transforming an ordinary stroll into an unparalleled geological expedition.

Consider the vibrant heart of downtown Seattle, where historical and modern structures stand as silent testaments to Earth’s dynamic evolution. At the intersection of Second Avenue and Cherry Street, for instance, a distinguished six-story edifice, a survivor and rebuilder from the devastating 1889 Great Fire, proudly displays blocks of rough-hewn sandstone. Quarried from Tenino, Washington, these formidable two-foot-tall blocks bear the weight of approximately 44 million years, offering a palpable sense of resilience and permanence that resonated deeply with a city rising from ashes. This sedimentary rock, formed from compressed sand over eons, encapsulates the erosion of ancient mountains and the deposition of their sediments in bygone seas or rivers, a testament to relentless geological cycles.

A short distance away, along Fourth Avenue, an elegant social club, distinguished on the National Register of Historic Places, showcases the subtle beauty of 330-million-year-old oatmeal-colored limestone sourced from Indiana. A closer inspection, perhaps with a simple hand lens, reveals a mesmerizing menagerie of fossilized marine invertebrates. Conical horn corals, the distinctive poker-chip-like stems of crinoids—ancient relatives of starfish—and the delicate, lace-like structures of bryozoans, colonial organisms resembling miniature Rice Chex, tell a vivid story of a shallow, vibrant Paleozoic sea that once teemed with life over three hundred million years ago. Limestone, a biogenic sedimentary rock predominantly composed of calcium carbonate from marine organisms, is a global cornerstone of architecture, its widespread use reflecting both its aesthetic appeal and the rich fossil record it often preserves.

Venturing further into the urban canyon, a modern 44-story skyscraper commands attention, clad in majestic 1.6-billion-year-old granite imported from Finland. On sunlit days, its intricate jigsaw-puzzle texture, a mosaic of red, white, black, clear, and veined crystals, radiates with a refulgent, almost otherworldly beauty. This igneous rock, formed from the slow crystallization of molten magma deep within Earth’s crust during the Proterozoic Eon, speaks of immense tectonic forces and volcanic activity that shaped the nascent continents. The sheer age of this Finnish granite connects Seattle directly to the ancient Fennoscandian Shield, one of Earth’s oldest and most stable continental blocks, illustrating the global provenance of urban building materials and the profound journey these stones undertake.

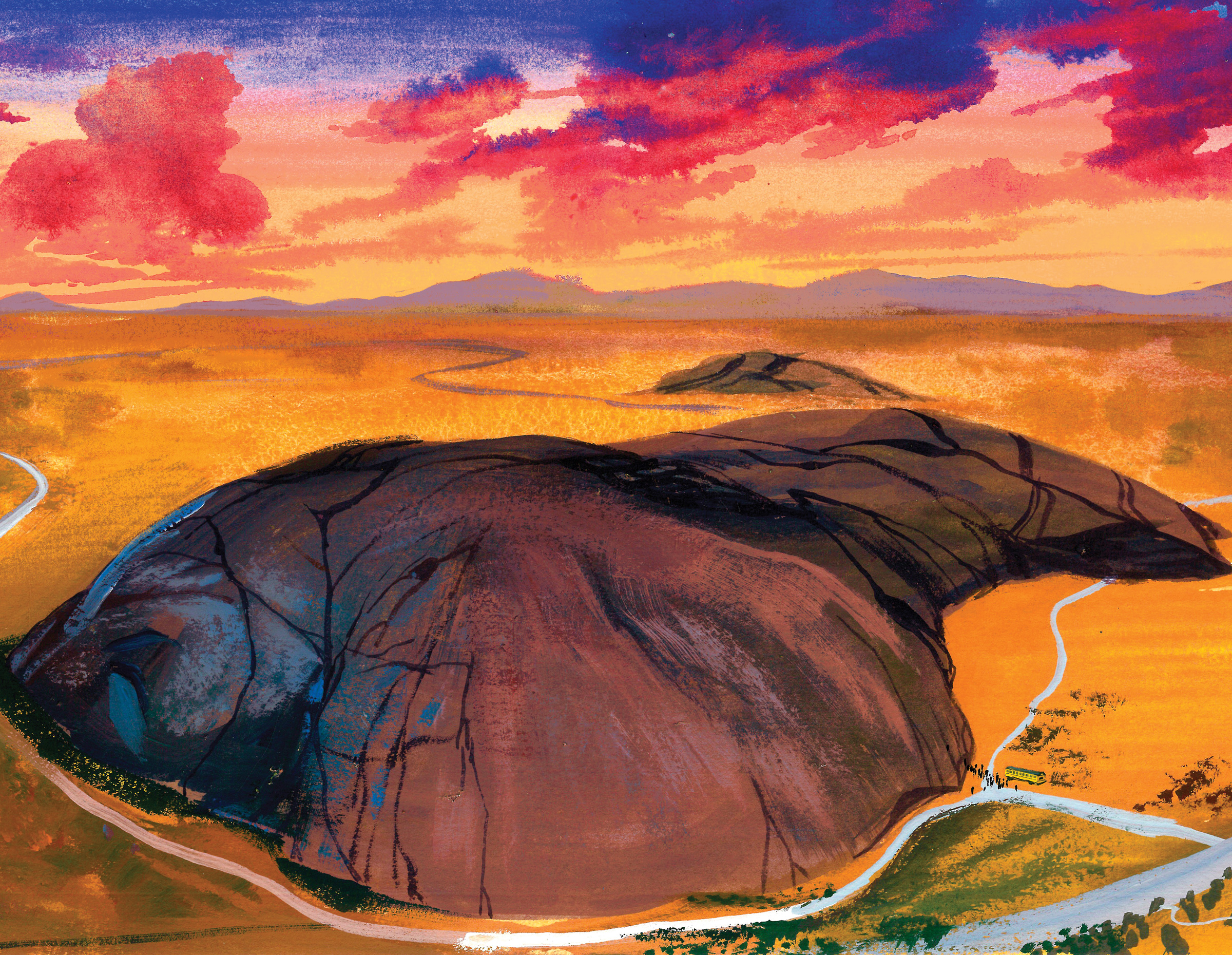

For many, the initial connection to this urban geological spectacle is a deeply personal one. The transition from the dramatic, erosional landscapes of Utah’s red-rock country, where sandstone canyons speak volumes of millennia of wind and water, to the historical urbanity of Boston initially presented a disconnect. Yet, the realization that the "brownstone" of iconic structures like Harvard Hall shared the same iron-stained sandstone composition as the beloved Utah formations forged a powerful bridge, reaffirming the universal language of geology. This re-engagement with Earth’s deep past, initially found in sweeping vistas, proved equally accessible within city limits.

This profound urban geological awakening reached its zenith upon returning to Seattle. It was there, on the side of the Exchange Building at Second Avenue and Marion Street, that a truly ancient marvel awaited: a stone composed of swirling pink and black blobs, layers, and convolutions, reminiscent of an abstract painting. This was Morton gneiss, a metamorphic rock quarried in Minnesota, its multihued patterns a direct result of immense pressure and temperature transforming pre-existing rocks deep within Earth’s crust. The astonishing revelation that this stone was 3.52 billion years old, dating back to the Archean Eon, connected the observer to a period when Earth itself was a mere youngster.

Touching that ancient, yet remarkably accessible, stone offered an unparalleled connection to serious deep time. It transported one back to an era when Earth’s fundamental geological processes, such as plate tectonics, might not have operated in the way they do today. Life on the planet was exclusively microbial; complex plants and animals were billions of years in the future. The Earth’s surface lacked the vibrant colors and biological diversity we now take for granted. This fragment of Morton gneiss, integrated into a modern building, tells a silent but eloquent story of a young Earth, still finding its footing, where the very existence of the planet we know and cherish was far from a certainty. It speaks of the formation of the earliest continental crusts, the stable cores around which continents would eventually grow.

Seattle is by no means unique in this regard. Nearly every city across the globe offers a similar, diverse array of geological treasures—granite, marble, limestone, sandstone, slate, and gneiss—often rivaling the geological diversity found in natural landscapes within such a compact area. These building stones are not merely inert construction materials; they are geological archives, each with a unique origin story. Generally, pure white or mottled cladding panels frequently consist of marble, a metamorphic rock formed from limestone. Fine-grained stones, often exhibiting distinct layering and containing fossils ranging in size from a pea to a cinnamon roll, typically indicate sandstone or limestone. Multihued or "salt-and-pepper" varieties are often granite, with its characteristic interlocking crystal structure. A basic guide to rocks and minerals can empower any curious urban explorer to begin deciphering these ancient messages.

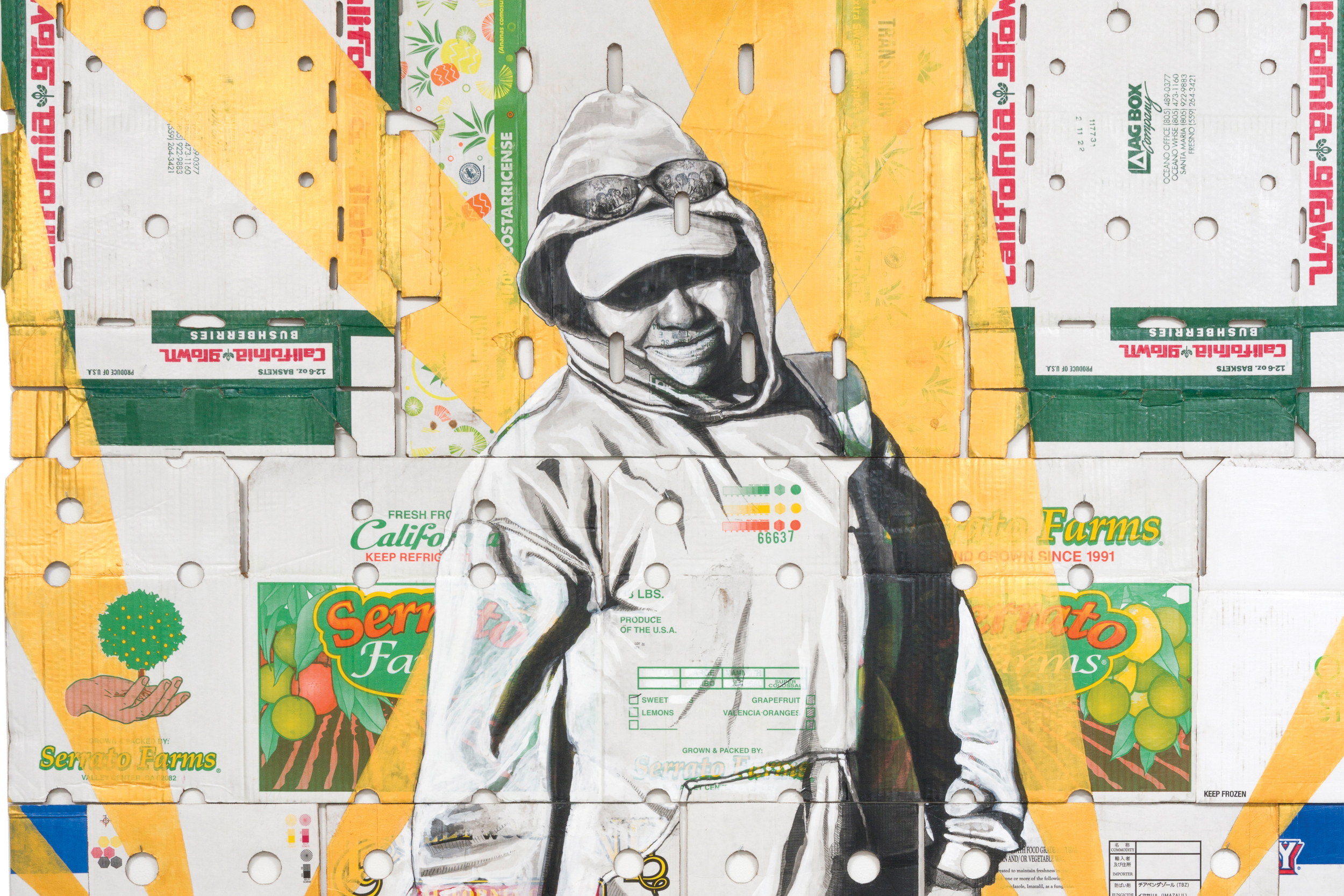

The global trade in building stones further enriches this urban geological tapestry. Materials from quarries across continents—Italian marble, Indian granite, Chinese slate—converge in a single city, each carrying the geological signature of its place of origin. This interconnectedness highlights not only the economic forces driving architectural choices but also the universal human desire for beauty, durability, and a connection to the Earth’s enduring materials. From the ancient Roman aqueducts built with local tufa and travertine to modern skyscrapers adorned with exotic granites and marbles, building stones have always been fundamental to human civilization, reflecting available resources, technological capabilities, and aesthetic preferences.

We are often conditioned to believe that a true encounter with nature necessitates a journey into the wild, far from human habitation. However, this perspective overlooks the omnipresent geological narrative embedded within our cities. Nature, in its most profound and ancient form, is all around us, visible in the very stones beneath our feet and above our heads, for anyone willing to slow down, observe, and pay attention. These urban geological tours offer more than just a historical curiosity; they provide a powerful perspective on the vastness of geological time, challenging our anthropocentric views and fostering a deeper appreciation for the planet’s enduring processes. They remind us that human history is but a fleeting moment in Earth’s grand, ongoing epic, a silent reminder of the persistent geological change that continues to shape our 4.54-billion-year-old planet.