In Tucson, Arizona, a profound shift is underway, moving beyond traditional habitat restoration to a philosophy of "reconciliation ecology," which encourages a deeper, more accepting connection with local landscapes, even in their altered states. This movement, catalyzed by the environmental awakenings of the 1960s and the subsequent decades of conservation and restoration efforts, now reframes the narrative for human-dominated environments. Instead of solely aiming to "restore" a degraded urban riparian corridor, practitioners now speak of "reconciliation," a concept gaining traction as a vital approach to increasing biodiversity within areas profoundly shaped by human activity, essentially offering a new paradigm for conservation in the Anthropocene.

Angelantonio Breault, a fourth-generation resident of Tucson, vividly recalls his childhood perception of the region’s floodplain as a mere "ditch." His perspective transformed as he delved into ecological studies and began visiting the Santa Cruz River on Sundays, drawn by the allure of its birds and wildflowers. This immersion fostered a sense of stewardship and a personal connection to the river, inspiring him to launch the "Reconciliación en el Río Santa Cruz" community initiative. This endeavor distinguished itself from earlier environmental campaigns by prioritizing a reimagining of human engagement with the land over a strict restoration agenda.

The roots of this evolving environmental consciousness in Tucson can be traced back to the 1960s, a period marked by growing awareness of air and water pollution, alongside devastating environmental incidents such as oil spills and the widespread use of pesticides. By this time, unchecked development had led to the severe overexploitation of surface and groundwater resources, leaving many local creeks and rivers desiccated for significant portions of the year. While Phoenix, located a couple of hours to the north, pursued relentless expansion and new housing developments, Tucson’s local environmental groups and nonprofit organizations forged coalitions to advocate for more controlled growth. Within a decade, the city had begun purchasing farmlands west of its boundaries, retiring them to alleviate pressure on groundwater reserves. Concurrently, smaller water systems were consolidated under the city-run Tucson Water, establishing a unified structure and agenda focused on the responsible stewardship of water resources across the valley.

This concerted effort paved the way for pioneering water conservation strategies. In 1977, Tucson launched its inaugural "Beat the Peak" campaign, aimed at raising public awareness about water consumption during peak hours and promoting the use of wastewater for landscape irrigation. Demonstrating a commitment to innovative water management, Tucson became one of the first cities in the United States to recycle treated wastewater for use in parks and golf courses by 1984. The persistent advocacy of activists who championed slower growth for years culminated in the formation of a coalition dedicated to protecting the habitats of 44 vulnerable, threatened, and endangered species. Their efforts also spurred the creation of bond-funded land conservation programs, established a robust system for preserving open spaces, and implemented measures to mitigate the impacts on vital riparian habitats. These initiatives ultimately led to the development and adoption of the Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan by the Pima County Board of Supervisors in October 1998. This comprehensive plan initially set forth two primary objectives: the protection of endangered species and the imposition of significant restrictions on development, but over time, its scope has broadened to encompass environmental restoration, wildlife crossings, and stormwater harvesting.

The 200-mile Santa Cruz River, which traverses Tucson en route from northern Mexico, serves as a compelling example of how Tucsonans have positioned themselves at the vanguard of urban conservation. The river’s ecosystem suffered greatly during the early 20th century as overgrazing, excessive groundwater extraction, and infrastructure development intensified, leading to the devastation of its riverbed. By the 1950s, the section of the Santa Cruz River flowing through Tucson had completely dried up.

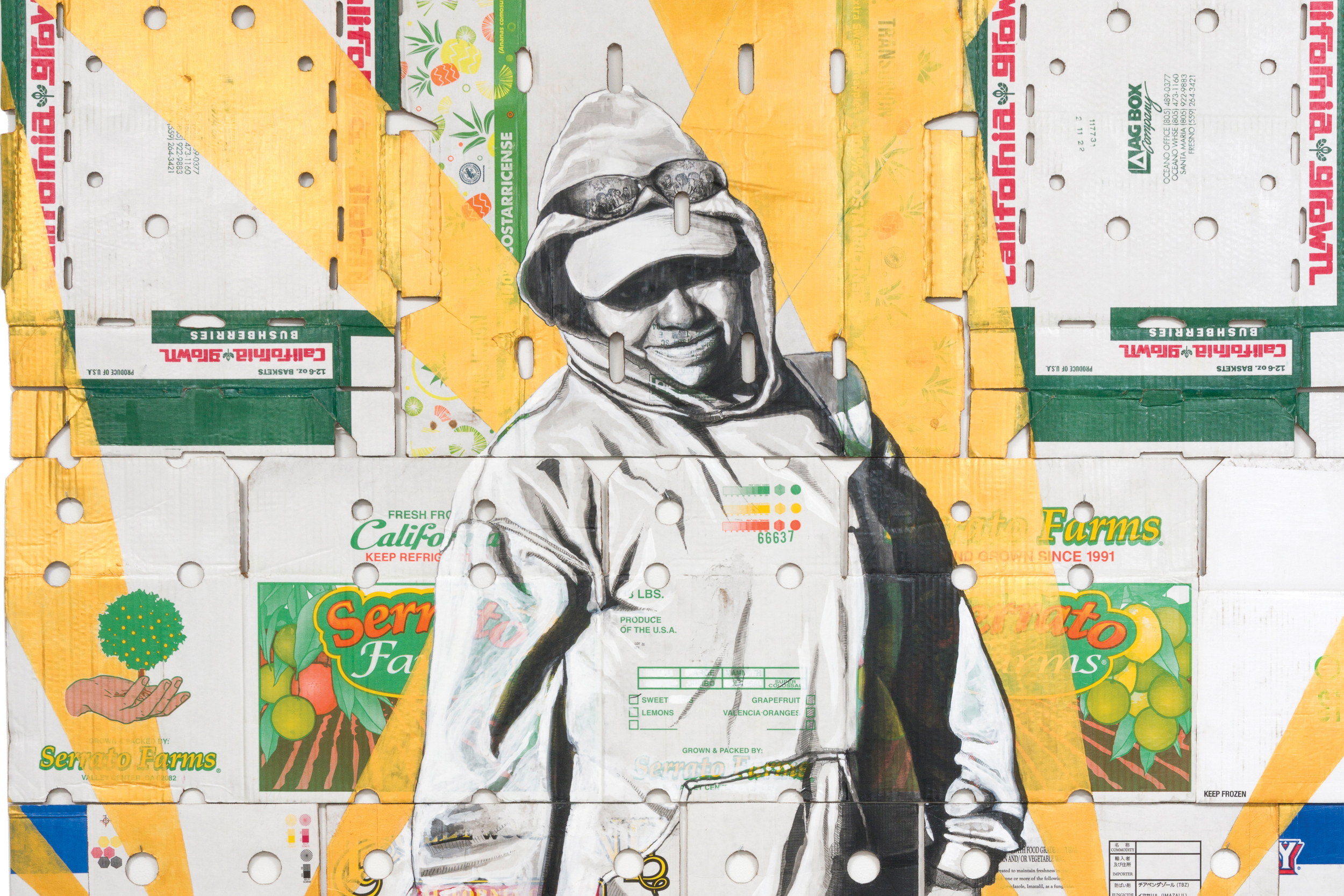

Decades later, local ecologists recognized the urgent need to advocate for the river and the communities that depended upon it. However, Breault and his contemporaries faced a challenge: the Santa Cruz, choked with trash and ravaged by drought, seemed beyond the reach of conventional restoration standards advocated by scientific experts and traditional conservationists. They envisioned a different path – one of reconciliation. "I see the Santa Cruz as a portal," Breault explained, "a way for people to explore the authentic relationships they already have with the natural world." He firmly believes that the most effective method for engaging the public lies in "participatory stewardship programming," asserting that individuals "don’t need to have their hand held." Breault’s philosophy centers on enabling people to forge their own connections with nature, irrespective of the past human impacts, exploitation, or abuse that these environments may have endured. Even ecosystems as degraded and parched as the Santa Cruz, he argues, possess the inherent capacity to sustain life and discover avenues for thriving.

This philosophy of active engagement and ecological reconnection found a tangible manifestation in 2017. Following the discovery of the endangered Gila topminnow downstream of the Nogales International Wastewater Treatment Plant, Tucson Water initiated the diversion of up to 2.8 million gallons of treated recycled water daily into the river south of downtown, a crucial step to replenish the aquifer and its associated riparian habitat. A dedicated team of scientists from the Arizona Game and Fish Department and the University of Arizona undertook the delicate task of collecting over 700 Gila topminnows from upstream locations. These fish were then carefully transported to a release point near downtown Tucson, in an area where the once-polluted river had entirely dried up.

This initiative, undertaken in 2020, has yielded remarkable results. Today, the Santa Cruz River flows with renewed vitality for approximately a mile near downtown Tucson. While some sections remain ephemeral, others boast perennial flow, creating a dynamic and ever-changing landscape. Following significant monsoon rains, the river surges freely, but even in their absence, the continuous release of treated effluent is sufficient to support the resurgence of wetlands and marshes. Cottonwoods, which had vanished from the area more than sixty years ago, are making a comeback. The Gila topminnow is reproducing, and an impressive 40 other native animal and plant species have returned to the river corridor. Crucially, people have also returned, participating in organized trash cleanups, impromptu invasive plant removals, and simply enjoying wildlife observation.

Breault encourages this renewed engagement, suggesting, "Get in line. Do what you do best; tell stories." He is orchestrating a series of gatherings along the river, envisioning everything from storytelling workshops and art-making meetups to interpretive nature walks, while also observing a growing number of similar events organized by others. "We don’t have to do everything," he stated. "The river knows. We just have to be down there together." This sentiment encapsulates the essence of reconciliation ecology: a collaborative, accepting, and deeply personal journey of rediscovering and nurturing life in landscapes shaped by human presence. The revitalization of the Santa Cruz River serves as a potent symbol of hope and a testament to the possibility of coexisting harmoniously with the natural world, even in the heart of urban environments.