The vast, ancient canvas of the American West, particularly the rugged expanses of Wyoming, offers a profound lens through which to examine Earth’s geological saga and humanity’s fleeting, yet impactful, presence. Growing up amidst this monumental scenery, with a father whose life was intimately tied to the Earth’s subterranean secrets, provided a unique perspective on the immense scales of time and the indelible marks left by both natural forces and human endeavor. My early years were punctuated by the sporadic returns of my father, a petroleum geologist, from remote oil rigs in the Powder River Basin. These distant outposts, often isolated "man camps" in the pre-cellular era, epitomized a global industry’s relentless quest for energy, a pursuit that has profoundly shaped modern civilization and left its own complex geological signature on the planet.

The Powder River Basin, a vast intermontane depression stretching across northeastern Wyoming and southeastern Montana, has long been a vital hub for energy extraction, first for coal, and later for oil and natural gas. Its geological formations, rich with fossil fuels, dictated much of my father’s professional life, a life characterized by extended periods of absence and the distinct scent of gasoline and grease upon his return. These early experiences, coupled with the dramatic fluctuations of the global energy market, profoundly influenced our family dynamics. The boom-and-bust cycles inherent in the petroleum industry, driven by geopolitical events and shifting global demand, meant periods of intense activity followed by sudden lulls. During one such downturn, my father’s increased presence at home led to an unconventional daily ritual: the "New Word Light" and "Question Corner" on our drives to school, where he would impart vocabulary and engage in profound discussions, from existential queries about divinity and suffering to the weighty realities of the Vietnam War and personal loss. It was during one of these commutes that he first introduced the incomprehensible concept of deep time: if Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history were compressed into a single 24-hour day, humanity would only emerge in the final few seconds before midnight. This stark revelation underscored the brevity of human existence against the backdrop of geological eons, yet ironically, it is within these brief seconds that we have managed to leave an unprecedented and increasingly global mark.

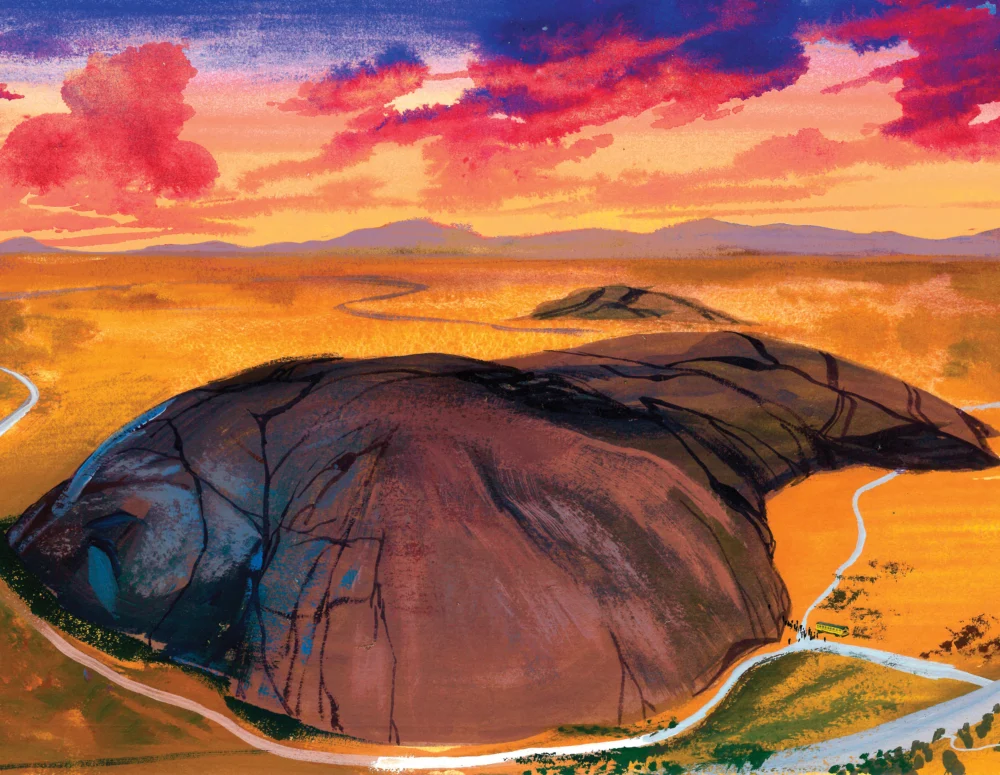

One of the most potent symbols of this interwoven history of deep time and human inscription is Independence Rock, a monolithic granite outcrop in central Wyoming. For generations of schoolchildren, myself included, field trips to this landmark were an annual pilgrimage, a journey to what we affectionately called "the turtle of the prairie." Its immense, rounded form, indeed reminiscent of a colossal turtle shell nestled amidst the sagebrush, belies its profound historical and geological significance. Located an hour from Casper, this natural wonder served not only as a backdrop for childhood picnics and lessons in wilderness survival but also as a tangible link to a pivotal era in American history.

Independence Rock holds a unique place as the "Register of the Desert," a testament to the sheer scale of the 19th-century westward migrations. More than 5,000 names, dates, and messages were meticulously carved or painted onto its surface by an estimated half-million pioneers who traversed the arduous Oregon, Mormon, and California Trails. These inscriptions, often crude yet deeply personal, transformed the rock into a vast, open-air bulletin board, a poignant record of hope, struggle, and perseverance. The act of carving one’s name onto this enduring sentinel was a profound declaration of existence, a fleeting assertion of individuality against the backdrop of an immense and unforgiving landscape. In recognition of this extraordinary legacy, the state of Wyoming designated Independence Rock a national historic landmark in 1961, preserving its unique role in the narrative of American expansion.

Physically imposing, the rock rises 136 feet above the surrounding plains, akin to a 12-story building. It spans 27 acres and measures over a mile in circumference, 700 feet wide and 1,900 feet long. Its distinctive name originates from fur trappers who celebrated Independence Day there in 1830, long before the major pioneer waves. However, the rock’s history stretches back far beyond these European-American encounters. For millennia, numerous Indigenous tribes from the Central Rocky Mountains, including the Arapaho, Arikara, Bannock, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Crow, Kiowa, Lakota, Pawnee, Shoshone, and Ute, revered this granite monolith. They knew it as "Timpe Nabor," the Painted Rock, leaving their own, often spiritual and symbolic, carvings and petroglyphs, reflecting a deep, symbiotic relationship with the land that predated and contrasted sharply with the more utilitarian markings of the pioneers. These ancient markings serve as a vital reminder of the rich tapestry of human history that unfolded in this region for thousands of years before the arrival of European settlers, a testament to diverse cultural expressions and enduring connections to place.

The descriptions penned by pioneers, meticulously recorded by historians, offer a fascinating glimpse into their perceptions of this colossal formation. John Ball, in 1832, envisioned it as "a big bowl turned upside down," comparing its size to "two meeting houses of the old New England Style." Lydia Milner Waters saw it as "an island of rock on the grassy plain," while Civil War soldier Hervey Johnson humorously noted its resemblance to "a big elephant (up) to his sides In the mud." Others likened it to a huge whale or an apple cut in half and turned over. These varied interpretations highlight the human tendency to project familiar forms onto the unfamiliar, seeking to comprehend the monumental through relatable analogies.

As the daughter of a geologist, I approached Independence Rock with a deeper appreciation for its fundamental composition and formation. It is, in geological terms, a granite boss—an intrusive igneous feature formed when molten rock, or magma, pushes up from deep within the Earth’s crust but cools and solidifies before reaching the surface. Over millions of years, the softer overlying sedimentary rocks eroded away, exposing this resistant core. The immense pressure from below, coupled with subsequent weathering processes, sculpted it into its distinctive rounded, dome-like shape. Wyoming, a landscape sculpted by aeons of geological activity, is replete with such "ventifacts"—rocks meticulously molded by the persistent force of wind, a process often termed "wind-faceting." At Independence Rock, this grand narrative of geological transformation began over 50 million years ago with exfoliation, where water seeped into fissures, and the relentless cycle of freezing and thawing gradually pried apart the granite grains. Thin sheets of crumbling rock were then washed away by rain and snow, continually exposing fresh rock beneath. Finally, around 15 million years ago, persistent windblown sand further rounded its top, finalizing the dome we see today. These processes, unfolding over unimaginable timescales, are not unique to Wyoming but are fundamental to shaping landscapes across the globe, from the arid deserts of the Sahara to the glacial valleys of the Himalayas, illustrating the universal language of Earth’s geodynamics.

My connection to this deep time remains palpable, even as my father, now 85, exhibits his own form of "weathering." His face, etched with the sun and wind of a lifetime spent outdoors, and his gait, a little less steady, tell a story of enduring engagement with the Earth. Yet, his passion for geology remains undimmed; he still embarks on dinosaur digs, forever shaped by the very forces he studies. I often joke that I, too, am a ventifact, molded by the relentless Wyoming wind and the vast, open spaces that fostered a profound sense of scale and perspective. We are all, in essence, products of our environments—shaped by our parents, our education, and the countless journeys we undertake. For me, geology, with its grand narratives of creation and erosion, has been the most formative influence, instilling a deep appreciation for the transient nature of existence and the enduring power of the planet.

Recalling my ninth-grade lessons, where the geologic time scale became a rhythmic chant of "Paleozoic, Mesozoic, Cenozoic!" and "Jurassic, Triassic, Cambrian, Cretaceous!", I recognize these seemingly foreign words as the fundamental vocabulary of our planet’s autobiography. My father, my own steadfast "rock," patiently listened, absorbing every utterance, just as he had registered the pioneer carvings on Independence Rock. His influence, like the enduring granite, has left an indelible mark on me, a legacy I hope to pass on to my own daughters.

The concept of deep time, of humanity as merely a blip in the grand cosmic scheme—joining the party seconds before midnight—is not diminishing but rather profoundly comforting. Independence Rock, the enduring "turtle of the plains," will persist long after I am gone, long after my father is gone, a silent witness to countless eons. This profound longevity, its resilience against the elements, the historical inscriptions, and the fleeting celebrations of fur trappers, offers a unique form of optimism. It reminds us that our individual existences, however brief, are part of a much larger, ongoing narrative. We do not need to carve our names onto stone to affirm our presence; our collective human impact, for better or worse, is already woven into the geological fabric of the Anthropocene, the proposed new geological epoch defined by human-driven planetary changes. Understanding the immense history that precedes us fosters both humility and a sense of profound interconnectedness. It underscores the preciousness of our brief time and the responsibility we bear for the planet. In this vast continuum, each of us, in our own way, can serve as a "monolith" for others, guiding and shaping their journeys, just as the ancient rocks and the wisdom of our forebears guide ours. My father, though not literally enshrined in stone, will, in a very real sense, live on in the stories the rocks tell and the enduring geological wisdom he imparted.