In 2022, following a series of historic storms that ravaged remote villages across Western Alaska, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) engaged a California-based contractor to facilitate access to vital disaster aid for affected residents. The contractor’s primary responsibility was to translate applications for financial assistance into local Indigenous languages. This was a critical task, as the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, a sprawling region encompassing numerous small Alaska Native communities, is home to approximately 10,000 people who learn Yugtun, the Central Yup’ik dialect, as their first language, often before English. Farther north, an additional 3,000 individuals speak Iñupiaq, highlighting the profound linguistic diversity and the imperative for culturally and linguistically appropriate communication in the region.

However, when these purportedly translated materials were received and subsequently reviewed by journalists at the local public radio station, KYUK, they were found to be utterly unintelligible. The content was described as "nonsense," a grave failure that undermined the very purpose of the outreach. Julia Jimmie, a Yup’ik speaker and translator at KYUK, recounted her experience, stating, "They were Yup’ik words all right, but they were all jumbled together, and they didn’t make sense." Her poignant reflection on the incident — "It made me think that someone somewhere thought that nobody spoke or understood our language anymore" — underscored a deeper concern about respect and recognition for Indigenous cultures and languages. This incident not only delayed crucial aid but also eroded trust between federal agencies and the vulnerable communities they were meant to serve, raising serious questions about the efficacy and cultural competency of disaster response efforts in linguistically diverse, remote areas.

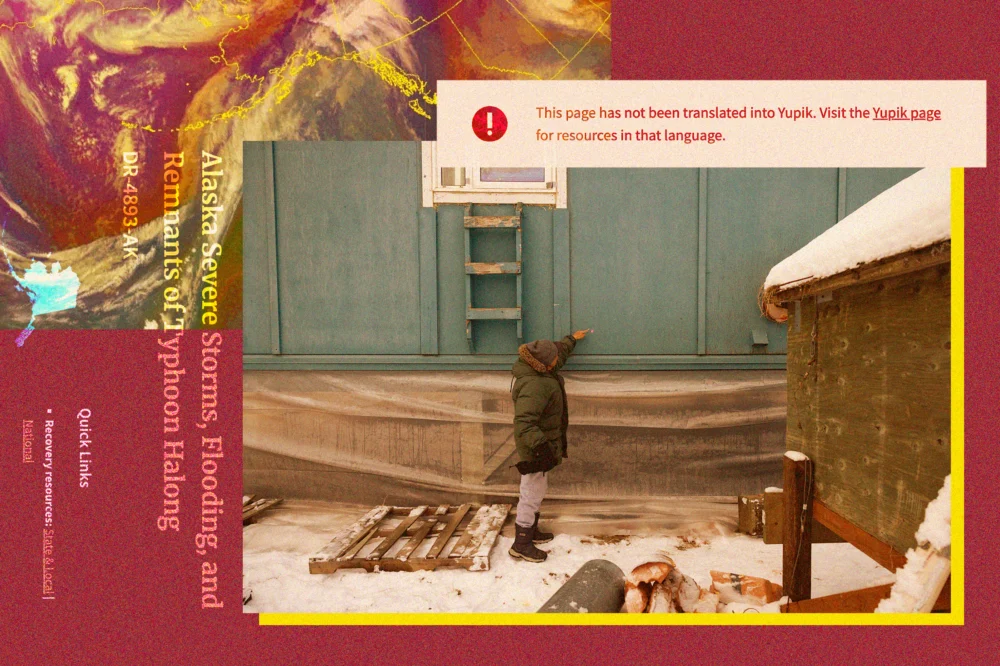

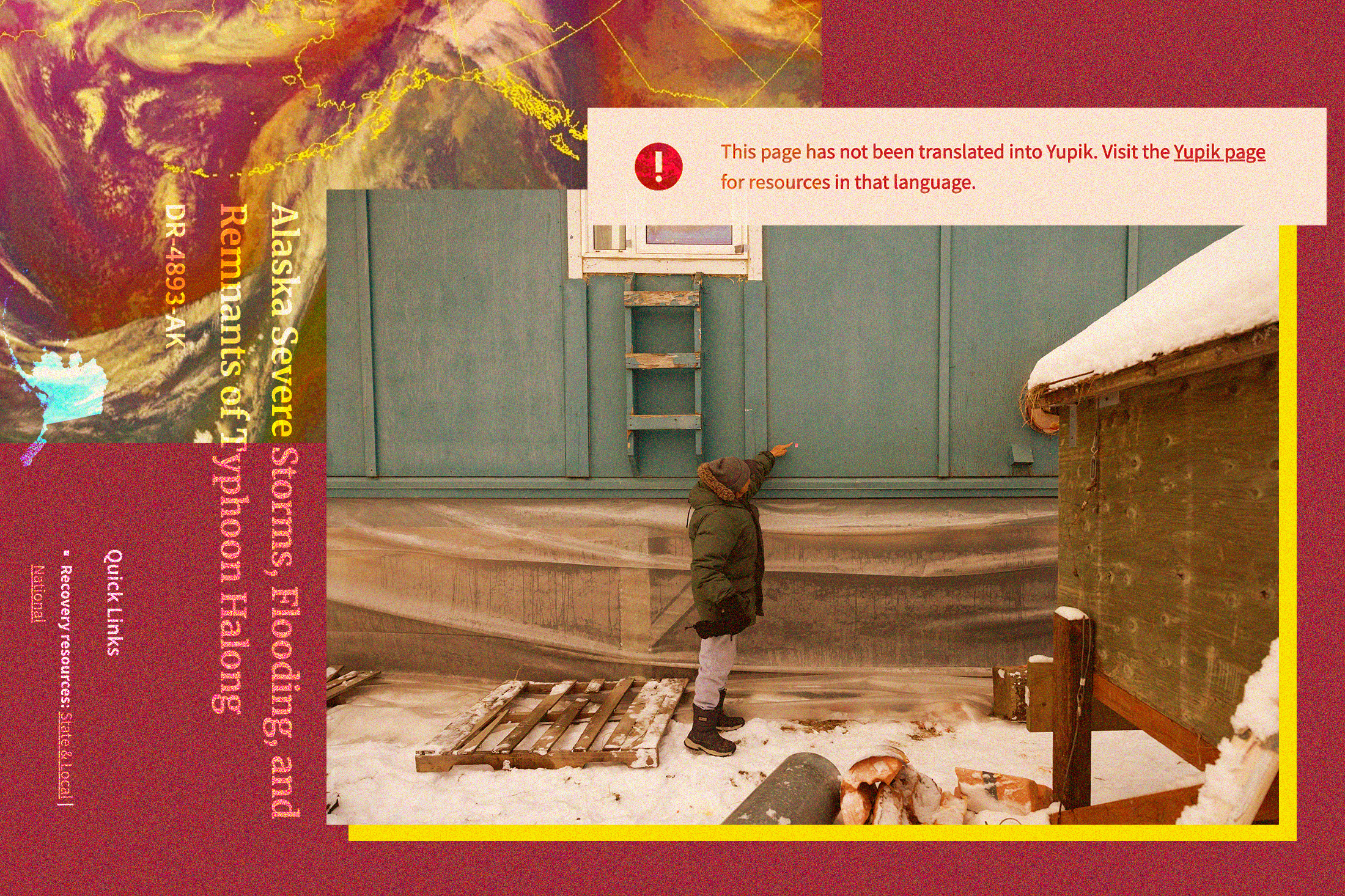

Just three years later, the region is once again grappling with the aftermath of a devastating natural disaster. Typhoon Halong, a powerful extratropical storm, swept through Western Alaska in mid-October, displacing more than 1,500 residents and claiming at least one life in the village of Kwigillingok. The remnants of the typhoon brought unprecedented flooding and structural damage to already fragile communities, exacerbating the challenges of recovery in a geographically isolated and climatically harsh environment. As communities struggled to rebuild, the issue of language access for disaster relief has resurfaced, but this time, it is entangled with a complex and rapidly evolving technological debate: the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in Indigenous communities.

The immediate aftermath of Typhoon Halong saw a Minneapolis-based company, Prisma International, posting job advertisements on October 21 for "experienced, professional Translators and Interpreters" of Yup’ik, Iñupiaq, and other Alaska Native languages. This recruitment drive came just a day before the Trump administration officially approved a disaster declaration for the storm, signaling a potential new wave of translation services. Government records indicate that Prisma has secured over 30 contracts with FEMA in recent years, establishing it as a significant vendor for the agency. Prisma’s corporate website prominently advertises its methodology, which "combine[s] AI and human expertise to accelerate translation, simplify language access, and enhance communication across audiences, systems, and users." The job listing itself explicitly stated that prospective Alaska Native language translators would be expected to "provide written translations using a Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) tool," directly implicating AI in the translation process for sensitive disaster relief materials.

Despite these clear indications, a spokesperson for FEMA declined in late October to confirm whether the agency intended to contract with Prisma for the Alaska response. Prisma International itself remained unresponsive to multiple inquiries via phone and email. However, the job posting’s preference for applicants with experience translating or interpreting "for emergency management agencies, e.g. FEMA," coupled with a requirement for knowledge of the recent storm and a connection to local Indigenous communities, strongly suggested a forthcoming engagement. Indeed, several Yup’ik language speakers in Alaska confirmed they had been directly contacted by a company representative, who identified Prisma as "a language services contractor for the Federal Emergency Management Agency." Among those contacted was Julia Jimmie, who, while open to translating for FEMA, expressed reservations and sought more information about working with Prisma, echoing the skepticism and caution prevalent within Indigenous communities regarding new technologies.

The expansion of AI into various facets of daily life, including translation, has generated a mixture of excitement and profound skepticism within Indigenous communities globally. Many Native technology and culture experts acknowledge the intriguing potential of AI, particularly its capacity to aid in language preservation and revitalization efforts for endangered dialects. However, this enthusiasm is tempered by serious warnings about the technology’s inherent risks: the potential for distorting invaluable cultural knowledge, perpetuating biases embedded in algorithms, and, most critically, threatening the fundamental principle of language sovereignty. Morgan Gray, a member of the Chickasaw Nation and a research and policy analyst at Arizona State University’s American Indian Policy Institute, articulates this concern succinctly: "Artificial intelligence relies on data to function. One of the bigger risks is that if you’re not careful, your data can be used in a way that might not be consistent with your values as a tribal community."

This issue extends beyond mere linguistic accuracy to encompass the broader concept of "data sovereignty," which asserts a tribal nation’s inherent right to define how its collective data is collected, stored, accessed, and ultimately used. While the U.S. government has yet to establish formal regulations for AI or its deployment, data sovereignty is increasingly becoming a central pillar of international discussions surrounding Indigenous intellectual property rights. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples explicitly enshrines the principle of free, prior, and informed consent for the utilization of Indigenous cultural knowledge. UNESCO, the United Nations body tasked with safeguarding cultural heritage, has consistently advocated for AI developers to respect tribal sovereignty when engaging with Indigenous communities’ data. As Gray emphasizes, "A tribal nation needs to have complete information about the way that AI will be used, the type of tribal data that that AI system might use. They need to have time to consider those impacts, and they need to have the right to refuse and say, ‘No, we’re not comfortable with this outside entity using our information, even though you might have a really altruistic motivation behind doing it.’" The lack of clarity regarding whether Prisma has formally engaged with tribal leadership in the Y-K Delta, with the Association of Village Council Presidents (a consortium of 56 federally recognized tribes) declining to comment, only deepens these concerns. Prisma’s website mentions an "AI Responsible Usage Policy" that clients can opt into, but the details of this crucial policy are not publicly available, further obscuring the company’s ethical framework for AI deployment.

In the three years since the disastrous translations of 2022, FEMA has reportedly taken steps to improve its engagement with Alaska Native communities. KYUK’s investigative reporting on the initial scandal not only brought the issue to public attention but also triggered a civil rights investigation into FEMA’s practices. The original California contractor was compelled to reimburse the agency for the faulty translations. A FEMA spokesperson confirmed that the agency now exclusively employs "Alaska-based vendors" for Alaska Native languages, prioritizing those situated within disaster-impacted areas to ensure local knowledge and faster response. Furthermore, a secondary quality-control review is now mandated for all translations, a measure designed to prevent a recurrence of the 2022 failure. The agency also stated that "Tribal partners are continuously consulted to determine language services needs and how FEMA can meet those needs in the most effective and accessible manner."

However, FEMA’s policies concerning the use of AI remain conspicuously vague. The agency’s email response did not directly address inquiries about specific policies regulating AI deployment or protecting Indigenous data sovereignty, instead offering a general assurance that FEMA "works closely with tribal governments and partners to make sure our services and outreach are responsive to their needs." This lack of explicit policy guidance from a federal agency dealing with vulnerable populations highlights a significant regulatory gap in the rapidly evolving landscape of AI ethics. Government records confirm FEMA’s extensive use of Prisma in over a dozen states, and Prisma’s website features a case study illustrating its "LexAI" technology used to provide disaster relief information in more than 16 languages, including "rare Pacific Island dialects," following a wildfire. While Prisma has worked with other federal agencies, it does not appear to have prior federal contracts in Alaska.

For Yup’ik language translators in the Y-K Delta contacted by Prisma, a practical, immediate concern loomed large: the fundamental accuracy of AI in translating their language. As Julia Jimmie observed, "Yup’ik is a complex language. I think that AI would have problems translating Yup’ik. You have to know what you’re talking about in order to put the word together." This complexity stems from the unique grammatical structure of languages like Yup’ik, which are polysynthetic, meaning words are formed by combining many morphemes (meaningful units) into long, complex expressions, often conveying what would be an entire sentence in English. Most AI models, particularly those relying on statistical machine translation or large language models, thrive on extensive datasets. Such comprehensive data is notoriously scarce for Indigenous languages globally, often resulting in AI producing inaccurate sentences, culturally inappropriate phrasing, or even entirely fabricated words. Research consistently demonstrates AI’s poor performance when tasked with translating low-resource languages, raising serious doubts about its suitability for critical disaster communication.

Sally Samson, a Yup’ik professor of language and culture at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, expressed deep skepticism that AI could genuinely master Yugtun syntax, which diverges substantially from English. Her concerns transcended mere informational accuracy, extending to the deeper cultural implications. "Our language explains our culture, and our culture defines our language," Samson eloquently stated. "The way we communicate with our elders and our co-workers and our friends is completely different because of the values that we hold, and that respect is very important." The nuanced worldview, traditional ecological knowledge, and intricate social protocols embedded within Indigenous languages risk being lost or misrepresented through automated translation, potentially undermining cultural identity and perpetuating misunderstandings during critical times.

In contrast to the external imposition of AI, Indigenous software developers worldwide are actively engaged in addressing the shortcomings of AI concerning Native languages, often with the express goal of language preservation and revitalization. These initiatives are distinct because Indigenous people are at the helm, developing the AI models and making crucial decisions about their application. For example, an Anishinaabe roboticist has innovated a robot to assist children in learning Anishinaabemowin, while a Choctaw computer scientist has successfully created a chatbot capable of conversing in Choctaw. These community-led efforts demonstrate a pathway for technology to serve Indigenous goals without compromising sovereignty or cultural integrity.

However, when private companies introduce AI without robust oversight and explicit consent, the potential for exploitation becomes a grave concern. Crystal Hill-Pennington, who teaches Native law and business at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and provides legal consultation to Alaska tribes, articulated a significant worry: the prospect of AI being trained on the invaluable work of Indigenous translators, with that data then being leveraged by non-Native companies for future commercial gain without ongoing engagement or benefit to the originating community. "If we have communities that have a historical socioeconomic disadvantage, and then companies can come in, gather a little bit of information, and then try to capitalize on that knowledge without continuing to engage the originating community that holds that heritage, that’s problematic," she warned.

Indigenous communities have endured centuries of external entities extracting and exploiting their cultural knowledge, often with devastating consequences. This historical context informs contemporary discussions around intellectual property and digital rights. A recent precedent for this kind of controversy emerged in 2022 when the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council took the drastic step of voting to banish a nonprofit organization. This organization had initially promised to assist in preserving the Lakota language but, after years of Lakota elders sharing their cultural knowledge, proceeded to copyright the material and subsequently attempted to sell it back to tribal members in textbook format. Hill-Pennington stresses that the integration of AI by private entities adds another complex layer to these ongoing intellectual property debates. "The question is, who ends up owning the knowledge that they’re scraping?" she queries, highlighting the critical need for clear ownership and governance frameworks.

Standards surrounding AI and Indigenous cultural knowledge are developing at a rapid pace, mirroring the swift advancements in the technology itself. Hill-Pennington acknowledges that some companies utilizing AI may still be unfamiliar with the expectation of informed consent and the intricate concept of data sovereignty. Nevertheless, she asserts that these standards are becoming increasingly pertinent and non-negotiable. "Particularly if they’re going to be doing work with, let’s say, a federal agency that does fall under executive orders around authentic consultation with Indigenous peoples in the United States, then this is not something that should be overlooked," she concluded. The ongoing dialogue in Alaska serves as a critical case study, underscoring the urgent need for federal agencies and their contractors to adopt ethical AI practices that uphold the self-determination, linguistic vitality, and cultural integrity of Indigenous peoples in disaster response and beyond.