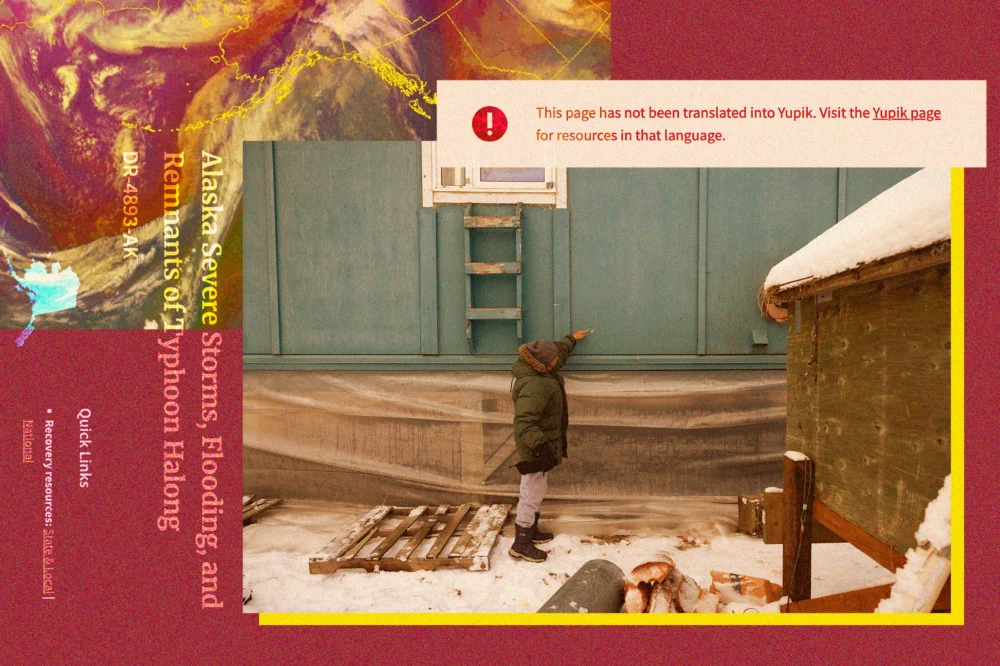

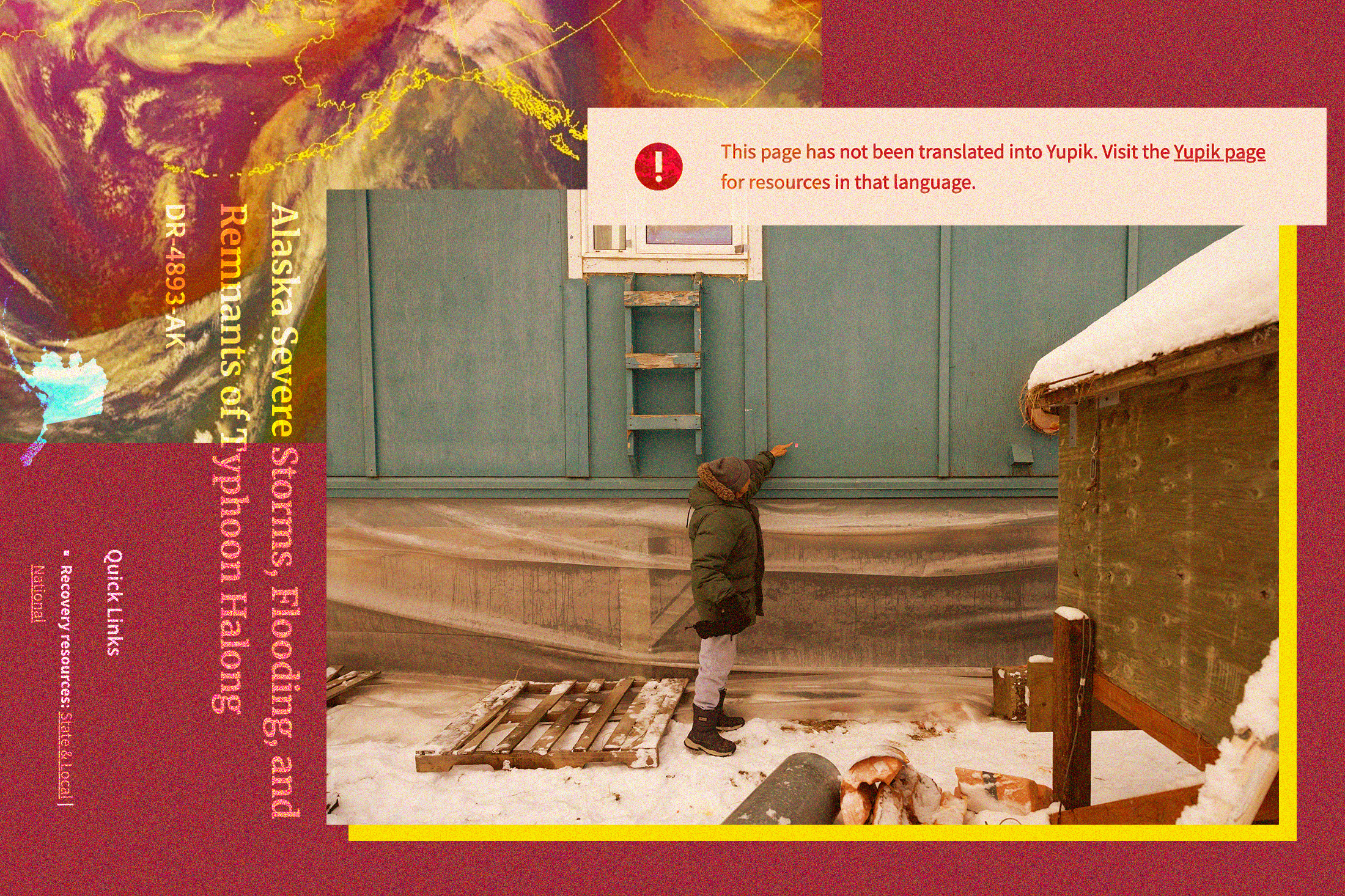

The remote villages of Western Alaska are once again grappling with the devastating aftermath of a powerful storm, Typhoon Halong, which in mid-October displaced over 1,500 residents and claimed at least one life in the community of Kwigillingok. As the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) mobilizes to provide crucial disaster aid, a familiar and deeply troubling issue has re-emerged: the integrity of language translation for the region’s predominantly Alaska Native populations, now complicated by the nascent role of artificial intelligence. Just days before the Trump administration approved a disaster declaration for the storm, Minneapolis-based Prisma International, a company touting its blend of "AI and human expertise," began recruiting for Yup’ik, Iñupiaq, and other Alaska Native language translators, sparking immediate apprehension among local linguistic experts and advocates.

This renewed concern is rooted in a recent, painful history that highlighted profound systemic failures in disaster communication. In 2022, following a series of historic storms that battered the same vulnerable communities, FEMA engaged a California-based contractor, Accent on Languages, to facilitate access to essential financial assistance. The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, a vast expanse dotted with small Alaska Native communities, is a vibrant hub of linguistic diversity. Approximately 10,000 Yugtun speakers, representing the Central Yup’ik dialect, comprise nearly half the region’s population, many of whom learn their Indigenous language before acquiring English. Further north, in other remote areas, roughly 3,000 individuals speak Iñupiaq. Yet, when the promised translations of critical disaster relief applications arrived, they were met with profound dismay. Local public radio station KYUK journalists and community members, including Yup’ik translator Julia Jimmie, described the materials as "nonsense"—a jumble of Yup’ik words that conveyed no coherent meaning. Jimmie’s poignant observation that it "made me think that someone somewhere thought that nobody spoke or understood our language anymore" underscored a profound breach of trust and cultural disrespect, demonstrating a critical failure to uphold the rights of Indigenous peoples to access vital government services in their native tongues. The incident not only highlighted severe operational deficiencies but also triggered a civil rights investigation into FEMA’s practices, ultimately leading to Accent on Languages reimbursing the agency for the faulty work. In response, FEMA stated it would now prioritize "Alaska-based vendors" for Native language services and implement a secondary quality-control review for all translations, alongside continuous consultation with tribal partners.

Despite these assurances and the gravity of the previous translation debacle, the emergence of Prisma International in the current disaster response has reignited the debate. Prisma, a company that has secured over 30 contracts with FEMA in recent years, posted a job advertisement for Alaska Native language translators on October 21, explicitly mentioning the use of "Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) tool." This term often encompasses various forms of machine translation and AI algorithms, which analyze vast datasets to produce linguistic conversions. While a FEMA spokesperson declined to confirm any direct contract with Prisma for the Typhoon Halong response, and Prisma itself remained unresponsive to inquiries, several Yup’ik speakers in Alaska confirmed being contacted by a company representative identifying Prisma as a FEMA language services contractor. This development immediately raised red flags, prompting questions about whether history might repeat itself, albeit with new technological complexities, and whether FEMA’s revised policies are adequately addressing the challenges of accurate and culturally sensitive communication in crisis zones.

The expansion of artificial intelligence into diverse spheres, including language translation, elicits a complex mix of hope and apprehension within Indigenous communities worldwide. On one hand, many Native tech and cultural experts acknowledge AI’s transformative potential, particularly in the vital arena of language preservation. Projects like an Anishinaabe roboticist designing a robot to teach Anishinaabemowin, or a Choctaw computer scientist creating a conversational chatbot in Choctaw, exemplify how Indigenous-led AI initiatives can empower communities to revitalize endangered dialects and pass on linguistic heritage to younger generations. These efforts are often driven by an intimate understanding of the languages and cultures they aim to support, ensuring that technology serves community-defined goals. However, this optimism is tempered by deep-seated concerns that the technology, if not carefully managed and ethically deployed, could inadvertently distort precious cultural knowledge and undermine the fundamental concept of language sovereignty, especially when developed and controlled by external entities.

At the heart of this apprehension lies the crucial issue of data. AI models fundamentally rely on vast datasets for training and operation, a process that can inadvertently lead to the exploitation of linguistic and cultural resources if not governed by strict ethical guidelines. Morgan Gray, a member of the Chickasaw Nation and a research and policy analyst at Arizona State University’s American Indian Policy Institute, articulates this concern: "One of the bigger risks is that if you’re not careful, your data can be used in a way that might not be consistent with your values as a tribal community." This brings to the forefront the critical concept of "data sovereignty"—the inherent right of a tribal nation to define and control how its data is collected, accessed, and utilized. While the U.S. government currently lacks formal, comprehensive regulations for AI or its application, the principle of free, prior, and informed consent for the use of Indigenous cultural knowledge is enshrined in international frameworks like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Furthermore, UNESCO, the UN body responsible for cultural heritage, has explicitly urged AI developers to respect tribal sovereignty when engaging with Indigenous communities’ data, emphasizing the necessity of complete transparency, meaningful consultation, and the unequivocal right to refuse.

The lack of clarity surrounding Prisma’s engagement with tribal leadership in the Y-K Delta further exacerbates these concerns. The Association of Village Council Presidents, a consortium representing 56 federally recognized tribes in the region, offered no comment on whether they had been consulted regarding Prisma’s activities or the use of AI in translation services. While Prisma’s website mentions an "AI Responsible Usage Policy" and allows clients to opt for human-only translation, the specifics of this policy are not publicly available, leaving critical questions unanswered about data governance, intellectual property, and ethical safeguards. FEMA, despite its stated commitment to tribal consultation and improved vendor practices, remained vague on its own AI policies, particularly concerning the protection of Indigenous data sovereignty, stating only that it "works closely with tribal governments and partners to make sure our services and outreach are responsive to their needs." This absence of explicit, transparent guidelines for AI use in federally mandated disaster relief efforts raises serious questions about accountability and adherence to ethical standards, especially in contexts where trust has already been eroded.

Beyond ethical considerations, practical linguistic challenges pose significant hurdles for AI in Indigenous languages. Julia Jimmie succinctly highlighted the inherent difficulty: "Yup’ik is a complex language. I think that AI would have problems translating Yup’ik. You have to know what you’re talking about in order to put the word together." Unlike analytical languages such as English, Yup’ik is polysynthetic and agglutinative, meaning words are often formed by adding numerous suffixes to a base root, creating intricate meanings that require deep cultural and contextual understanding. Such morphological complexity makes direct machine translation exceptionally difficult, as AI models typically rely on vast corpuses of existing text, which are largely unavailable for low-resource Indigenous languages. This "digital divide" in data availability means that AI has a documented poor track record with these languages, frequently producing inaccurate sentences, culturally inappropriate phrasing, or even entirely fabricated words, further compounding the communication breakdown during critical times when precision is paramount.

Sally Samson, a Yup’ik professor of language and culture at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, voiced a deeper concern: the potential for AI to strip away the cultural essence embedded within the language itself. She expressed skepticism that AI could genuinely master Yugtun syntax, which profoundly differs from English, fearing not just misinformation but a fundamental failure to convey the nuances of a Yup’ik worldview. "Our language explains our culture, and our culture defines our language," Samson emphasized. "The way we communicate with our elders and our co-workers and our friends is completely different because of the values that we hold, and that respect is very important." This speaks to the broader understanding that language is not merely a tool for communication but a vessel for cultural identity, ancestral knowledge, traditional values, and an entire way of life, elements that are highly dependent on human interpretation, lived experience, and profound cultural context. The loss of these nuances in machine translation represents a loss of far more than just words.

Crystal Hill-Pennington, who teaches Native law and business at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and provides legal consultation to Alaska tribes, cautions against the potential for exploitation when non-Native companies train AI on the invaluable work of Indigenous translators. She argues that "If we have communities that have a historical socioeconomic disadvantage, and then companies can come in, gather a little bit of information, and then try to capitalize on that knowledge without continuing to engage the originating community that holds that heritage, that’s problematic." This echoes centuries of Indigenous experience with outsiders extracting and commodifying their cultural knowledge and resources. A stark recent example occurred in 2022, when the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council took the unprecedented step of banishing a non-profit organization that had copyrighted Lakota language materials shared by elders, attempting to sell them back to tribal members. Such incidents highlight the tangible risks associated with unregulated data collection and the lack of robust intellectual property protections for Indigenous knowledge in the digital age. The core question, Hill-Pennington posited, is "who ends up owning the knowledge that they’re scraping?"

The rapid evolution of AI technology is occurring concurrently with an increasing global recognition of Indigenous rights and data sovereignty. While some companies might still be navigating these evolving ethical landscapes, Hill-Pennington asserts that these standards are becoming unequivocally relevant, particularly for entities contracting with federal agencies. "Particularly if they’re going to be doing work with, let’s say, a federal agency that does fall under executive orders around authentic consultation with Indigenous peoples in the United States, then this is not something that should be overlooked," she stated. As remote Alaska Native communities confront the twin challenges of climate change-induced disasters and the complex implications of emerging technologies, ensuring accurate, culturally sensitive communication, underpinned by explicit respect for Indigenous language and data sovereignty, remains a paramount and urgent imperative for all involved.