The allure of Montana first captured my imagination during my high school years, representing a profound sense of remoteness, untamed natural beauty, and the promise of adventure. In this vast Western landscape, I envisioned escaping the suffocating presence of lawyers and bankers, shedding the societal pressure to conform to their paths, and finding solace in a place where my aspirations wouldn’t be judged against such benchmarks. The idea of being there, alone, yet paradoxically feeling utterly connected, took root in 1985, a time when such unspoiled territories still seemed accessible within the contiguous United States.

My first tangible encounter with Montana occurred in 1997 when I embarked on a cross-country drive from Chicago to find a place to rent while pursuing graduate studies in Missoula. It was the height of summer, and the clarity of everything—the crisp air, the boundless sky, the crystal-clear waters—was astonishing. Each passing hillside beckoned me to pull over, abandon the car, and ascend its slopes. It was during this period that I began to appreciate Montana’s unique character, particularly its unconventional approach to traffic regulations. Upon my arrival, there was no daytime speed limit on the state’s highways; the only imposition had been a federally mandated limit during the 1970s energy crisis, a mandate Montana had largely circumvented. While speed limit signs were occasionally posted, they were rarely heeded, and law enforcement’s enforcement was more nuanced than punitive. Instead of citations for "speeding," drivers caught exceeding reasonable velocities were often issued tickets for "wasting fuel," with penalties, regardless of the speed (unless deemed reckless), capped at a nominal five dollars.

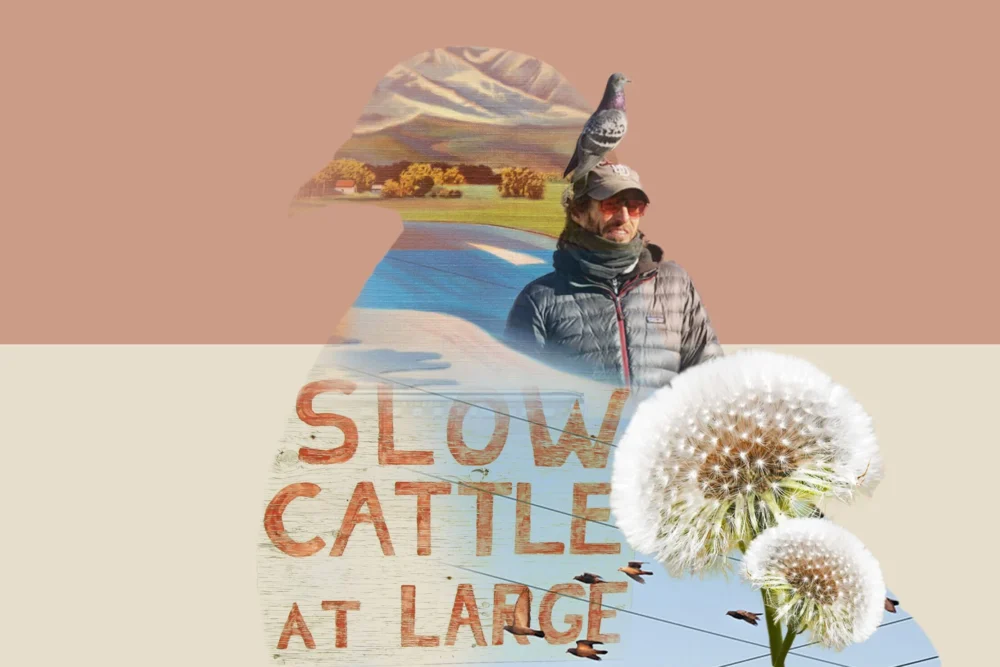

One of the initial curiosities that delighted me in Missoula was encountering a "CATTLE AT LARGE" sign. Prior to this, the phrase "at large" had primarily conjured images of escaped criminals or fugitives. This sign, however, prompted a reevaluation of my perception of cattle. Were they merely placid herbivores grazing by the roadside, or were they contemplating deeper matters, harboring hidden intentions behind their large, dark eyes? I recall a specific instance while driving on a secluded back road at approximately 50 miles per hour. Rounding a bend, I encountered a "CATTLE AT LARGE" sign, an immediate instruction to reduce my speed. This warning proved crucial, as a substantial shadow loomed ahead, a shadow that, without the sign’s prompt, I might have blundered into. This shadow, I soon realized, was a sizable cow resting placidly, occupying a significant portion of my lane.

The term "at large" literally translates to "with great liberty," signifying an expansive freedom to roam. This concept resonates deeply with the yearning for liberation often expressed by the protagonists in Bruce Springsteen’s narratives. Montana, with its vast expanses where fences are sparse and herds of thousand-pound animals can unexpectedly materialize on roadways, embodies this sense of unbridled freedom. This phenomenon mirrors the current state of my own home, which has become a sanctuary for numerous pigeons, a place where the boundaries between the human and natural worlds have blurred. Though I have long since departed from the urban sprawl, I now find myself residing in what I affectionately term "Pigeonopolis."

Among the young pigeons that now inhabit my home, one particular bird struggles with mobility. Even as a fledgling, it was apparent that maintaining an upright stance was a challenge. Its left leg would often drag behind, causing its hip joint to rotate unnaturally. Initial attempts to bind its legs together proved ineffective. My subsequent solution involved using specialized leg bands, plastic cuffs clipped just below the knee. To provide support without causing irritation, I fashioned a double loop of soft yarn attached to each cuff, designed to limit the outward splay of its legs and prevent chafing against its belly.

After a few weeks, as the pigeon transitioned into a young juvenile, I removed the cuffs. For a short period, it seemed to regain some stability, its feet remaining mostly beneath it. However, within days, the characteristic spraddle returned, and the hip joint once again assumed its awkward, inward orientation. Despite its physical limitations, this bird’s persistent efforts to navigate its environment with the grace of a "normal" bird have endeared it to me, making it a particular favorite. It has claimed a central position on my living room floor, directly in the path of the wide doorway leading to the kitchen, and it regards me with a watchful gaze. Though startled by my every passage, this remains its preferred spot, from which it shows no inclination to move.

In the hearthside cabinet resides another juvenile pigeon, one brought to me by neighbors, suffering from a broken wing. Additionally, a third juvenile occupies my living room; this one is the product of my caged female pigeon and a rather domineering male who has claimed a nesting box on the porch. This box was originally installed for Two-Step, my first pigeon, and his mate, V., though they never fully embraced it. The paternity of this particular juvenile is undeniable, as it bears no resemblance to its mother or her partner, but strikingly mirrors the "bully" pigeon. It appears that a few months ago, during a period when the cage was moved onto the porch, allowing the flightless couple some supervised outdoor time, the female engaged in a brief, yet consequential, liaison with the interloper. Remarkably, her original partner remains devoted, their bond unbroken. They move in tandem, mirroring each other’s actions, whether foraging for dandelion leaves or resting closely together, wing to wing, within the confines of their cage.

This "beautiful bastard," as I’ve come to call it, now ambles through my living room, quite "at large," searching for a comfortable spot on the floor to settle. This avian activity serves as a welcome distraction, as I too am considered "disabled," at least by legal definitions. The gentle presence of these birds is also remarkably meditative, offering a soothing balm to my persistent headaches. At certain times of the day, all three young pigeons engage in the rhythmic flicking of their feathers, a sound that fills the room with a calming cadence. Two-Step and V. occupy their nesting box beside me, separated by the window, where they benefit from the residual warmth radiating from the house. I have just adjusted the blinds, simulating twilight within their enclosure, hoping to encourage a more natural sleep cycle. Soon, I too will retire, and in the quiet sanctuary of our shared dreams, we will all find a measure of peace and safety.

Currently, my household hosts twelve birds, a dynamic mix of those in flight and those navigating the floors. While I have endeavored to foster a sense of wildness in them, they are gradually becoming more accustomed to my presence. My hope is that come spring, when I release them into the wider world, they will quickly learn to distinguish and fear creatures that resemble me. They have steadily begun to assert their presence, encroaching upon my personal space. Last night, for instance, two perched on the back of the couch, one nestled in a cardboard box beside me, another atop the miniature faux Christmas tree directly in front of me, and, as my legs were propped on the coffee table, one boldly stood on my toes before making its way up my leg. I must have resembled a character from a whimsical animated film. A sudden movement or a sneeze on my part would have undoubtedly sent them into a flurry of wings and feathers, creating delightful chaos. However, I had no compelling reason to stir; I remained still, a human statue in a park, adorned by pigeons. I found myself captivated by the delicate spread of their pink toes and the peculiar gait of the bird ascending my leg, its proximity allowing me to observe the intricate flecks within the golden ring around its eye.

The happiness of these birds brings me profound joy. I cherish these creatures and am immensely grateful for the sense of companionship they provide, dispelling the pervasive feeling of loneliness. Serving as their shepherd has become a central purpose in my life. As my understanding of their needs and behaviors deepens, I find myself adopting a more "birdlike" demeanor, which, in turn, seems to alleviate their apprehension around me. On most days, my interactions with birds far outweigh my encounters with humans. Apart from the occasional embrace or a friendly fist bump, I have experienced very little physical contact with other people in a considerable time. Yet, I am touched by the birds—when they alight on my toes, when I gently handle the young ones while cleaning their enclosure, or when I offer Two-Step a bath. In the quiet hours spent on the couch, often passing the time aimlessly, a recurring thought surfaces: "I am becoming bird." Perhaps soon, I will begin to decipher the nuances of their communication. Perhaps I will awaken each day to greet a partner with contented, pleasant "chukking" sounds, and later, as the sun reaches its zenith, we will soar together, perching on telephone wires, gazing over the verdant treetops at the undulating green hills of Montana.

This essay is an excerpt, published with permission from "We Should All Be Birds" by Brian Buckbee with Carol Ann Fitzgerald, a 256-page hardcover book available from Tin House for $28.99 in 2025. Photo illustration credits include Brian Buckbee with one of his pigeons, courtesy of the author; Crazy Mountain and Yellowstone River, Montana, from The Tichnor Brothers Collection/Boston Public Library; and a cattle sign, courtesy of Paul Joseph/CC via Flickr. Copyright © 2025 by Brian Buckbee and Carol Ann Fitzgerald. We welcome reader feedback and submissions for letters to the editor. Please direct inquiries to [email protected] or submit through our website’s feedback form. Refer to our letters to the editor policy for submission guidelines. News organizations are welcome to republish our quality news, essays, and feature stories free of charge. Our articles are available for republication, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.