Narsiso Martinez, born in Oaxaca, Mexico, in 1977, arrived in the United States at the age of 20 with a vision that would eventually transform discarded materials into powerful artistic statements. He honed his craft, earning a Master of Fine Arts degree in drawing and painting from California State University, Long Beach, a city where he continues to live and work. His distinctive artwork has garnered international acclaim, appearing in exhibitions worldwide and finding a permanent home in the esteemed collections of institutions such as the Hammer Museum, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, the University of Arizona Museum of Art, the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon, and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

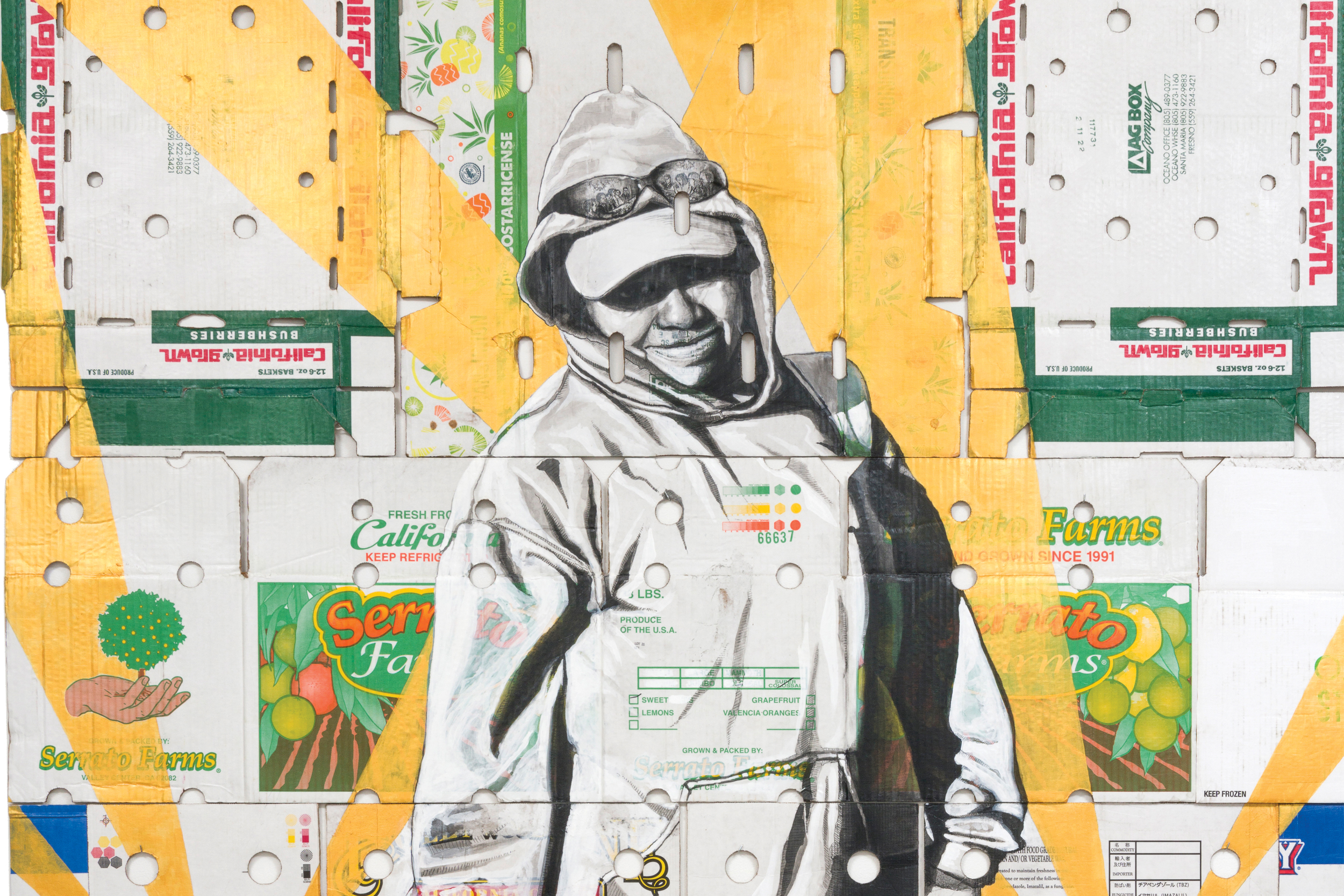

Martinez’s artistic journey took a pivotal turn around late 2016 or early 2017 when he began incorporating discarded produce packing materials into his art. This innovative approach stemmed from his practical experiences and a growing desire to represent the often-overlooked labor force that underpins global food production. Initially, while pursuing his graduate studies, Martinez found himself unable to afford traditional art supplies like oil paints and canvases. This financial constraint led him back to drawing on cardboard, a material he had previously used for sketches during his undergraduate years. He recalls collecting a banana box from a local Costco in Los Angeles and drawing a "banana man" on it, an act that was entirely personal and not for an academic assignment.

The true genesis of his signature style occurred when he presented this piece in class. With the insightful feedback from his classmates and faculty committee, the profound meaning behind his artistic choices began to crystallize. They recognized that Martinez was not merely depicting working-class individuals but was specifically focusing on agribusiness and the lives of farmworkers, a realization that deeply resonated with him. This confluence of circumstance, artistic experimentation, and community feedback marked the beginning of his dedicated exploration of the farmworker experience through art.

Martinez’s deep connection to his subject matter is rooted in his personal history. He began working in agricultural fields in 2009, shortly after transferring to Cal State Long Beach. Facing financial difficulties with tuition, he followed his family’s path into the fields, where they provided him with support for food and lodging. He recounts meticulously saving his paychecks, dedicating his time to field labor during every academic break, including three full years between undergraduate and graduate school, and every summer thereafter. This commitment meant he was actively involved in farm work for nearly nine years, often traveling to Washington state immediately after school ended and returning just before classes resumed to maximize his time in the fields.

The physical demands of this labor were significant. Martinez recalls the arduous task of picking asparagus, a job that required constant bending under the sun with no shade. He also harvested cherries, various apple varieties like Gala, Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, and Fuji, as well as peaches and blueberries. These firsthand experiences provided him with an intimate understanding of the challenges and realities faced by agricultural workers, fueling his artistic drive to bring their stories to light.

Through his art, Martinez aims to illuminate the vital, yet often invisible, contributions of farmworkers to society. He seeks to raise awareness of their presence, their significant impact on our food system, and their inherent humanity. His overarching goal is to "dignify farmworkers," recognizing that they have historically been marginalized and overlooked, both in the United States and globally.

The response from the farmworker community to his art has been profoundly moving. Having worked alongside many of them, Martinez developed personal connections, often sketching them in his notebook. He shares that when farmworkers see themselves reflected in his artwork, it instills a sense of validation and recognition, making them feel valued and acknowledged as integral members of society, akin to the feeling of importance he experienced upon receiving his first identification card. He has organized exhibitions specifically for farmworkers, which have elicited overwhelming emotional responses and generated rich exchanges of personal stories. Martinez hopes his art empowers them to see their own significance and the indispensable role they play in sustaining the nation.

The power of Martinez’s work extends to its commentary on the complex dynamics of the food system. He highlights the immense power farmworkers wield through their essential role in food production, while simultaneously critiquing the economic and political structures that often leave them vulnerable and disenfranchised. Reflecting on his own journey, Martinez observes that the systems in place often seem designed to perpetuate the oppression of farmworkers, a demographic historically composed of marginalized communities. He finds it deeply disheartening that these individuals, who nourish the nation, are frequently denied a dignified existence and are often used as political scapegoats. He expresses a hope that public support for legislation can pave the way for a more equitable and fulfilling life for farmworkers, acknowledging that throughout history, a truly dignified existence for them has remained elusive.

Martinez stresses the fundamental humanity of farmworkers, emphasizing that beyond their essential labor, they are individuals with diverse emotions, aspirations, dreams, and struggles. He asserts that it is time for society to acknowledge their full humanity, recognizing that they experience joy and sorrow, just like anyone else.

In the current socio-political climate, Martinez finds the targeting of agricultural workers particularly unjust and unacceptable. He draws parallels to the historic United Farm Workers Movement, inspired by leaders like Larry Itliong, Cesar Chavez, and Dolores Huerta, who fought for better conditions for farmworkers. He expresses gratitude for organizations that support farmworkers and advocate for their rights, especially in the face of policies that can lead to deportation or other forms of persecution. He expresses disbelief at images of military presence in agricultural areas, viewing it as a politically motivated tactic rather than a justified response.

The widespread recognition and inclusion of his work in major museum collections have come as a significant surprise to Martinez. He is deeply grateful that art created by an immigrant artist, particularly an Indigenous immigrant, can resonate with such a broad spectrum of audiences, including farmworkers themselves, academics, researchers, and museum-goers. This broad appreciation underscores the universal themes of dignity and labor that his art explores.

Martinez’s experience immigrating to the U.S. at a young age profoundly shaped his artistic perspective. Coming from a small Oaxacan village, the urban landscape of the United States presented a significant culture shock with its towering buildings, extensive road networks, and diverse cultural tapestry. He cherishes the multiculturalism and global influences he has encountered in America. The key to navigating this new environment, he found, was learning the English language, which he pursued through adult education. This educational pursuit empowered him to believe in his potential and to pursue higher education, ultimately enabling him to gain a more comprehensive understanding of his surroundings and his place within them.

His education also led him to a deeper understanding of his own heritage and the historical context of his homeland. He recognized the deep connection of Indigenous peoples to the land and the enduring impact of colonization. This realization fuels his ongoing exploration of the struggle for equity and inclusion for Indigenous communities, acknowledging the challenges but maintaining hope for progress.

Martinez sees his work as connected to the rich sociopolitical and labor-focused artistic traditions of Mexico, particularly the muralist movement. He acknowledges the influence of Mexican muralists like David Alfaro Siqueiros, whose powerful works, such as the "América Tropicale" mural, deeply impacted him, especially given his Zapoteca heritage. The principles of muralism, particularly the collaging of diverse images to create a cohesive narrative on a grand scale, resonate with his artistic process. He aspires to create art that evokes emotion and sparks critical thinking in viewers, much like the impactful works of the muralists.

Looking ahead, Martinez plans to broaden the scope of his artistic inquiry to encompass the global experiences of farmworkers. He recognizes that the struggles he depicts are not confined to the United States but are a pervasive reality worldwide. His future projects involve visiting and potentially working in orchards in other countries to foster direct connections and dialogue with farmworkers across different regions. He aims to explore the common threads that link the challenges faced by farmworkers in the United States with those in places like Nicaragua or Colombia, seeking to understand the underlying systemic issues that perpetuate their struggles. This global perspective will undoubtedly enrich his powerful artistic narrative, further highlighting the shared humanity and persistent fight for dignity among agricultural laborers worldwide.