The North American porcupine, a creature instantly recognizable by its formidable quilled defense, is becoming increasingly elusive across the Western United States, alarming both wildlife scientists and indigenous communities who fear a broader ecological unraveling. For generations, encounters with the stout, slow-moving rodent, known for its nocturnal foraging habits, were a common thread in the tapestry of forest life. Now, its absence casts a long shadow over ancestral lands and scientific understanding, prompting urgent investigations into its precipitous decline.

In Northern California, the Karuk Tribe grapples with a deepening void where porcupines once thrived. Emilio Tripp, a dedicated wildlife manager and a Karuk tribal citizen, vividly recalls a fleeting glimpse of a shadowy form during a nighttime drive with his father in the late 1990s. That memory, however indistinct, remains his only potential sighting of a kaschiip, the Karuk word for porcupine, in decades. At 43, Tripp finds himself among a generation whose firsthand experiences with the species are virtually non-existent, a stark contrast to the elders who fondly recount a time when porcupines were abundant until the turn of the century. Today, news of a porcupine is often a grim discovery – a carcass on a roadside or a fleeting, accidental encounter, signaling a species teetering on the brink of regional disappearance.

"Everyone’s concerned," Tripp articulated, underscoring the collective apprehension within his community. "If there were more observations, we’d hear about it." This sentiment echoes across the vast landscapes of the American West, where reports from British Columbia to Arizona and Montana indicate a widespread and alarming reduction in porcupine numbers. This vanishing act has spurred wildlife scientists into a frantic race to pinpoint remaining populations, unravel the complex causes of their decline, and, in a testament to enduring hope, inspire ambitious restoration projects, including those championed by the Karuk Tribe, aimed at reintroducing the species to its ancestral forests.

The North American porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum), distinct from its Old World and other New World cousins, is a creature of unique adaptations. Its most striking feature, an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 quills, offers an almost impregnable defense against most predators. These keratinous barbed spines detach easily upon contact, embedding themselves into an attacker, yet they are not thrown, as often mythologized. Despite this formidable armor, porcupines are often described as "big, dopey, and slow" by researchers like Tim Bean, an ecologist at California Polytechnic State University, who has extensively studied them. Their reliance on quills means they lack the speed and agility of many other rodents, moving deliberately between trees, primarily at night, to feed on foliage, buds, and the nutrient-rich inner bark (cambium) of various tree species. This diet, while vital for the porcupine, has historically placed it at odds with human interests, particularly the timber industry.

Throughout the 20th century, the economic value placed on commercial timber led to widespread persecution of porcupines. Viewed as destructive pests whose bark-gnawing habits could damage valuable lumber, they became targets of extensive poisoning and hunting campaigns. Vermont, for instance, reported the mass killing of over 10,800 porcupines between 1957 and 1959. In California, Forest Service officials declared an "open season" on porcupines in 1950, asserting that the species posed an existential threat to pine forests. While state-sponsored bounty programs eventually ceased by 1979, the lingering effects of decades of systematic eradication appear to have prevented a natural rebound. Modern surveys from diverse regions across the West consistently show porcupine populations remaining scarce, leaving scientists to ponder whether they are still declining or simply struggling to recover from historical decimation.

The anecdotal evidence, though not always scientifically quantifiable, is compelling. Veterinarians report fewer cases of pets arriving with embedded quills, a once-common rural occurrence. Longtime residents in forested areas notice the absence of the familiar porcupine scuttling through their backyards, and hikers lament that sightings are rarer than ever. This ecological imbalance has ripple effects throughout the food chain. In the Sierra Nevada mountains, the endangered fisher (Pekania pennanti), a member of the weasel family, is experiencing nutritional deficiencies. Historically, porcupines were a crucial protein source for fishers, who are among the few predators skilled enough to bypass their quilled defenses. Consequently, Sierra Nevada fishers are now noticeably scrawnier and produce smaller litters compared to their counterparts in areas where porcupines are more prevalent, illustrating the profound impact of a single species’ decline on an entire ecosystem.

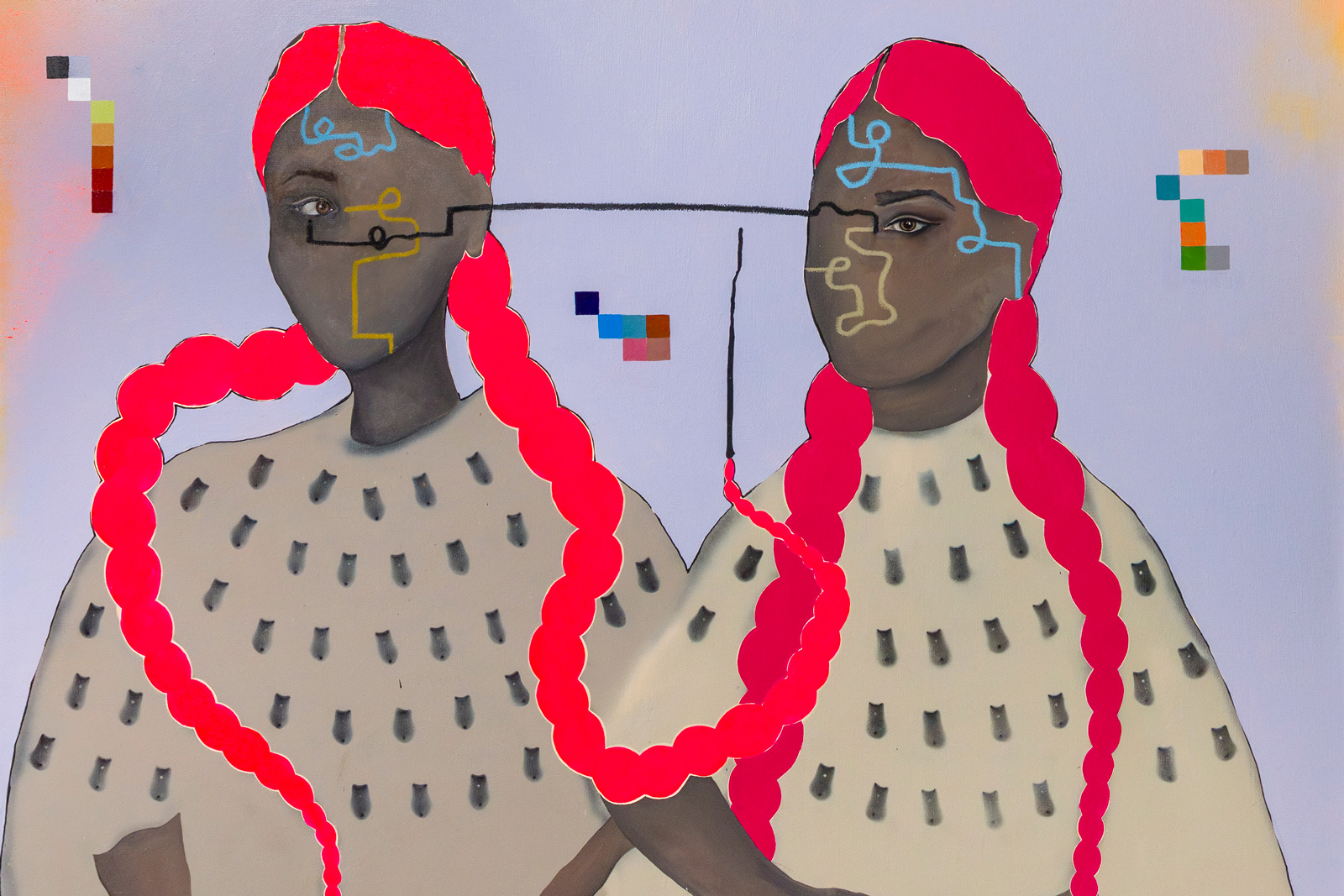

Beyond the ecological ramifications, the porcupine’s disappearance represents a significant cultural loss for indigenous communities like the Karuk Tribe. Porcupine quills have been meticulously woven into traditional Karuk basketry and other ceremonial items for generations, embodying a deep connection to the land and its creatures. The necessity of importing quills from distant regions rather than gathering them locally signifies more than a mere inconvenience; it represents a severance of cultural ties, a diminished connection between tribal members and their ancestral homelands. "It’s important for porcupines to be a part of our landscape," Tripp emphasized, highlighting how their presence is intrinsically linked to the cultural and spiritual fabric of the tribe. "That’s part of why they’re chosen to be part of this ceremonial item."

Erik Beever, an ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, views the porcupine’s plight as a microcosm of a much larger, more ominous trend. He warns of a "silent erosion of animal abundance" sweeping across the country, where biodiversity is diminishing at a rate faster than scientists can effectively monitor. The porcupine, therefore, serves as a poignant indicator of this widespread phenomenon, a canary in the ecological coal mine. The lack of historical baseline data further complicates the issue, leaving scientists grappling with fundamental questions. "We’re wondering whether the species is either increasing or declining without anybody even knowing," Beever acknowledged, underscoring the critical knowledge gap.

To bridge this gap, scientists are employing innovative methods. Tim Bean and his team at Cal Poly meticulously compiled a century’s worth of public records, including roadkill databases, wildlife agency reports, and citizen science observations, to map porcupine distribution patterns across the Pacific Northwest. Their research suggests a concerning trend: porcupines are dwindling in their traditional conifer forest habitats but appear to be colonizing non-traditional environments, such as deserts and grasslands, possibly driven by habitat alteration or changing resource availability. Beever is now expanding this crucial work to encompass the entire Western U.S., seeking to piece together a comprehensive picture of the species’ current status.

Several theories attempt to explain why porcupines have not recovered in their historical ranges. The proliferation of illegal marijuana cultivation sites, often clandestinely tucked away in remote forest areas, poses a significant threat. These illicit farms frequently employ highly toxic rodenticides to protect crops, indiscriminately poisoning non-target species, including porcupines, and contaminating the broader ecosystem. Additionally, conservation successes for apex predators like mountain lions, while vital for overall ecosystem health, may inadvertently contribute to porcupine decline by increasing predation pressure on an already vulnerable population. Compounding these challenges is the porcupine’s inherently low reproductive rate; females typically birth only a single offspring, known as a porcupette, making population recovery exceptionally slow and rendering the species highly susceptible to environmental stressors. Other potential factors include habitat fragmentation, increased wildfire frequency altering forest structures, and even climate change impacting food sources and denning sites.

Studying such an elusive, nocturnal, and widely distributed herbivore presents unique logistical challenges for researchers. Porcupines are generalists, inhabiting a broad array of forest types, which makes targeted surveying difficult. Unlike many other species, they are not easily lured by conventional baits. Scientists have experimented with various attractants, including brine-soaked wood blocks, peanut butter, and even porcupine urine, to coax them towards camera traps, but with only mixed success. John Buckley, executive director of the Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center, highlighted this difficulty, noting that in 34 years of extensive camera trap surveys in the Sierra Nevada, porcupines have appeared only three times. "It’s a mystery," Buckley conceded, expressing frustration at the lack of understanding regarding why populations are not rebounding even in undisturbed habitats like Yosemite National Park.

Despite the formidable obstacles, the Karuk Tribe remains resolute in its commitment to bringing porcupines back to its lands. Initial camera trap surveys within Karuk territory have yielded scant evidence, with one area considered a "hotspot" recording a single porcupine sighting. "That’s how rare they are," Tripp lamented. Undeterred, Karuk biologists are exploring alternative, less invasive methods, such as utilizing trained conservation dogs to conduct scat surveys, which can provide valuable genetic and dietary information.

The prospect of reintroducing the species involves a delicate balancing act. Given the current scarcity, it remains uncertain whether existing, already diminished porcupine populations can sustain the removal of individuals for translocation elsewhere. However, Tripp believes that immediate action is imperative, as the ecosystem demonstrates no signs of self-correction. "Things don’t seem to be getting better in over the course of my lifetime," he observed, underscoring the urgency of human intervention. Yet, a quiet optimism persists. Tripp, his wife, and daughter continue to participate in basket-weaving events, incorporating quills into their craft, an age-old tradition that honors the porcupine and its place in Karuk culture. This enduring dedication embodies a stubborn hope—a profound belief that, with sustained effort and a renewed connection to the land, the Karuk Tribe will one day be able to welcome the kaschiip home, restoring not just a species, but a vital piece of their heritage and a cornerstone of the Western ecosystem.