While the stoic presence of ancient trees, with their gnarled branches and ring-laden trunks, offers a profound sense of continuity and resilience, true portals to Earth’s most distant past lie beneath our feet, etched into the very rocks that form our landscapes. These geological formations, often perceived as silent and immutable, are, in fact, eloquent chroniclers of deep time, offering invaluable insights into the planet’s tumultuous history – a history increasingly pertinent to our anxieties in the Anthropocene. Rather than a mere collection of inert minerals, these "Natural Intelligence" archives provide a mature counterpoint to humanity’s burgeoning artificial constructs, ready to impart perspective-altering memories to those patient enough to listen. Wyoming, in particular, stands as an unparalleled geological library, boasting surface rock exposures that represent nearly 80% of Earth’s existence, from 3.5 billion years ago to the present, making it one of the most comprehensive and continuous geological records on the planet.

Our journey into Wyoming’s profound past begins with the Sacawee Gneiss, the state’s oldest exposed rock, crystallized approximately 3.45 billion years ago during the Paleoarchean Era. This venerable formation, found within the Granite Mountains, originated from the melting of even older granitic rocks, remnants of which now survive only as microscopic zircon crystals within the Sacawee’s intricate fabric. These tiny, durable zircons act as geological time capsules, their uranium-lead decay ratios precisely dating the epoch of their formation. The early Earth that witnessed the birth of the Sacawee Gneiss was a dramatically different realm: a nascent planet significantly hotter and more geologically volatile than today, its surface a chaotic mosaic of magmatic activity. True continents had not yet coalesced; instead, a scattering of granite islands dotted a restless globe, with plate tectonics still in its infancy. The Sacawee Gneiss, along with its ancient counterparts in southern Minnesota and northern Michigan, endured immense pressures and temperatures deep within the Earth’s crust, undergoing a spectacular metamorphosis that left it intricately folded and banded – a testament to the colossal forces that shaped our planet. Unbeknownst to these primordial rocks, they were laying the groundwork for one of Earth’s first stable continental masses, a tectonic cornerstone geologists now refer to as the Superior Craton. This ancient craton later experienced profound rifting, separating the Sacawee from its siblings as a vast ocean opened, only for subsequent plate motions to reverse course, leading to a monumental collision that birthed the Trans-Hudson mountain belt. While these colossal mountains have long since succumbed to erosion, their deep roots still peek through in Wyoming’s Medicine Bow Mountains, with the majority now lying buried beneath younger strata in the Dakotas and Saskatchewan, a silent monument to ancient continental assembly. Exposed at the surface today, the Sacawee Gneiss slowly undergoes its own reincarnation, gradually transforming into sediment, a poignant reminder of rock’s eternal cycle of destruction and rebirth.

Following this fiery foundation, the Nash Fork Dolomite, dating back some 2.1 billion years to the Paleoproterozoic Era, offers a starkly different narrative from its exposures in the Medicine Bow Mountains. This sedimentary rock formation speaks of a "water world," a vibrant shallow ocean that once divided the nascent Superior Craton. In this energetic epoch, the Moon’s closer proximity resulted in significantly higher tides, and Earth’s faster rotation compressed the day to a mere 19 hours. Crucially, land plants were absent, yet these ancient waters teemed with photosynthesizing cyanobacteria. These microscopic organisms were the architects of one of Earth’s most transformative events: the Great Oxidation Event. Prior to this, Earth’s atmosphere was dominated by volcanic gases, primarily carbon dioxide and water vapor. The relentless metabolic activity of cyanobacteria, however, began to flood the oceans and atmosphere with free oxygen, fundamentally altering the planet’s chemistry and paving the way for more complex life forms. These early microorganisms formed vast, resilient, and symbiotic communities known as stromatolites – lumpy, layered mats of diverse microbial species that thrived in the shallow seas. These "cabbage-like" structures, preserved within the Nash Fork Dolomite, underscore the profound lessons in diversity and deep recycling essential for durable communities. Geologists recognize their significance, declaring outcrops of these spectacular stromatolites "no-hammer zones." The Nash Fork Dolomite challenges humanity’s often "size-ist" perception of the biosphere, reminding us that single-celled organisms dominated Earth for billions of years, buffering atmospheric and oceanic chemistry long before the advent of animals. The emergence of large, complex animal life, with its elaborate food webs and insatiable appetites, ultimately introduced a vulnerability to the carbon cycle, making the biosphere susceptible to the mass extinctions that would punctuate later eras.

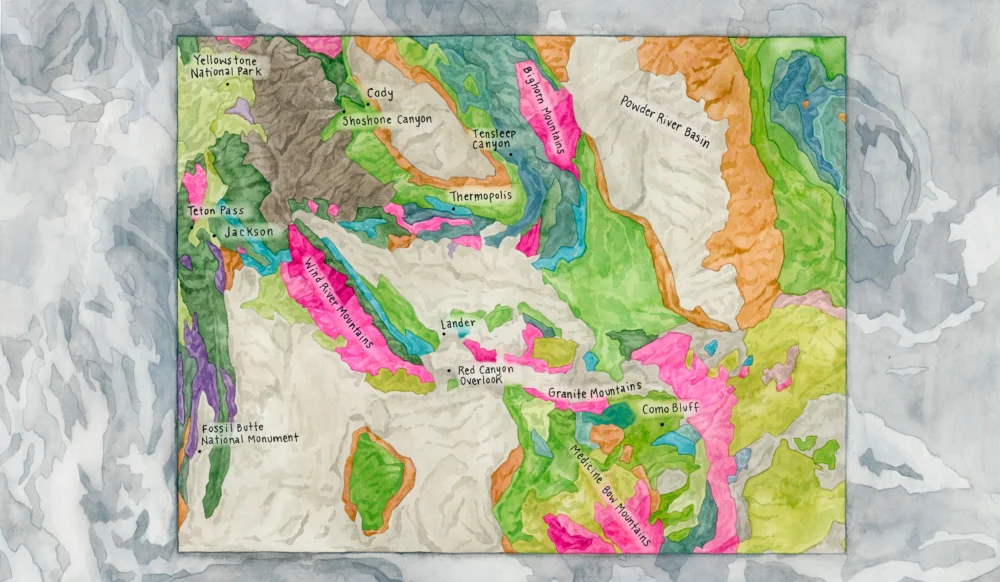

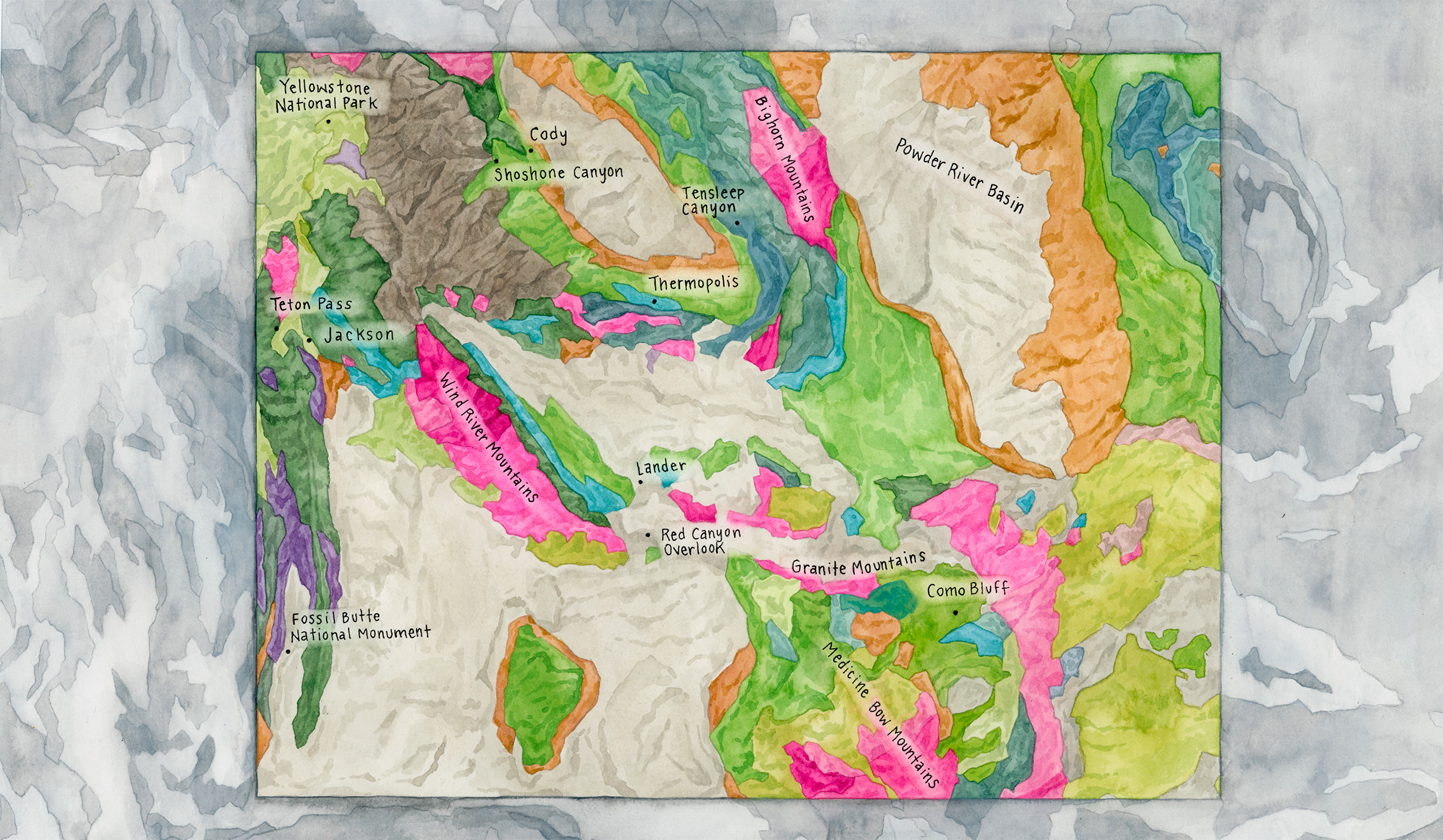

The ancient ocean that bore the Nash Fork Dolomite eventually vanished, compressed by the tectonic collision that formed the Trans-Hudson mountains. A subsequent era of intense erosion, lasting over a billion years, carved deeply into the bedrock, creating a vast, irregular surface known as the Great Unconformity. In Wyoming, this monumental gap in the geological record spans the Mesoproterozoic Era to the Early Cambrian Period, a testament to the immense power of geological time and erosional processes. Though it represents an absence – a "nonentity" or "un-rock" in traditional terms – this irregular surface, visible in the Big Horn and Wind River ranges and Shoshone Canyon, is globally renowned, notably in the Grand Canyon, where its dramatic exposure captivates observers. Its existence points to an extended period of low sea levels, preventing sediment accumulation and allowing mountains to be painstakingly dismantled, layer by layer, by the forces of weathering and erosion.

As Earth emerged from a prolonged and extreme cold spell, the "Snowball Earth" glaciations that had encased continents in ice, global temperatures rose dramatically. The melting ice caps led to a massive rise in sea level, inundating the deeply eroded continental landscapes. The Flathead Sandstone, approximately 520 million years old from the middle Cambrian Period, records this grand marine transgression. Forming a vast sheet of beach sand, now lithified into stone, it blankets the Great Unconformity across North America, with equivalents like the Tapeats Sandstone in the Grand Canyon and the Potsdam Formation in New York. The Cambrian Wyoming it knew was an austere land, devoid of plants, but a geological tapestry of exposed Sacawee-like gneisses and Nash Fork-era dolomites. The Flathead Sandstone, composed almost entirely of quartz, speaks volumes about the immense volume of igneous and metamorphic rock that had to be weathered and eroded over a billion years to yield such purity. Geologists, who once considered these quartz sandstones "inarticulate" due to their seemingly uniform composition, have recently unlocked their secrets through the study of "detrital zircons." These rare, resilient zircon grains, carried by ancient rivers from distant igneous and metamorphic source rocks, act as microscopic identifiers, allowing scientists to reconstruct long-vanished continental drainage systems. This discovery transformed these seemingly silent sandstones into libraries of paleogeographic information, revealing the intricate pathways of ancient sediment transport.

Millions of years later, as Earth’s climate cooled and seas retreated once more, a new landscape emerged, dominated by arid conditions. The Tensleep Sandstone, dating to roughly 310 million years ago in the late Carboniferous Period, vividly records this transformation. Exposed in the Bighorn Mountains and Tensleep Canyon, this sandstone is a product not of water, but of merciless wind, formed from vast desert dune fields. Its quartz grains, pitted and scarred to the point of opacity, bear the indelible marks of eons of aeolian abrasion. Eventually, a rising sea, the Phosphoria Sea, advanced from the west, burying and preserving the Tensleep Sandstone. This marine inundation, a welcome relief from the desert’s torment, ironically set the stage for its later exploitation. The exceptional biological productivity of the Phosphoria Sea created rich organic matter that, over geological time, decomposed into petroleum, seeping into the Tensleep’s permeable dune sands. Today, this formation is extensively perforated by countless oil and gas wells, a direct consequence of its ancient geological history, fueling modern economies while simultaneously drawing parallels to past environmental calamities.

The Phosphoria Formation itself, approximately 290 million years old from the early Permian Period, chronicles a time of extraordinary biological exuberance along Wyoming’s western continental margin. Exposed along modern highways near Jackson and Lander, this formation speaks of a tropical marine paradise where warm, sunlit waters, enriched by upwelling coastal currents, fostered a vibrant ecosystem. The seafloor teemed with brachiopods, sea snails, and sponges, forming living carpets, while phytoplankton thrived at the surface. The Phosphoria’s shales and limestones preserve scales from an astonishing variety of fish, including the bizarre Helicoprion, a shark-like creature with a fearsome spiral saw of teeth. This "phosphatic euphoria," however, was tragically short-lived. The formation serves as a grim forewarning, preceding the most severe mass extinction in Earth’s history: the end-Permian event. Enormous eruptions of lava in what is now Siberia released colossal volumes of carbon dioxide, triggering a cascade of environmental disasters including abrupt global warming, ozone depletion, ocean acidification, and widespread anoxia, ultimately leading to the collapse of nearly 80% of marine species. The profound irony is that humanity’s dependence on the very resources preserved within formations like the Phosphoria – its phosphate-rich shales mined for fertilizer and its organic matter fueling our oil-driven economy – is propelling us towards a similar environmental catastrophe, echoing the ancient Permian cataclysm.

In the aftermath of this near-total biosphere collapse, the Chugwater Group, dating to around 240 million years ago in the Triassic Period, painted Wyoming’s landscape in striking shades of red. This easily recognizable formation, visible across the Wind River, Bighorn, and Powder River basins, records a post-apocalyptic world: hot, arid, and sparsely vegetated. Braided rivers meandered across this parched terrain, depositing sands and silts, while intermittent brackish basins evaporated, leaving behind white lenses of gypsum. The Chugwater’s brilliant vermillion hue, a result of trace amounts of oxidized iron or rust, serves as a colorful marker of an environment where oxygen levels remained low for millions of years after the Permian extinction, as marine photosynthesizers slowly struggled to re-aerate the oceans. This oxygen-deprived world may have favored the evolution of certain reptile groups, with paleontologists suggesting that the efficient respiratory systems of early dinosaurs – a trait passed down to modern birds – gave them a crucial advantage. Indeed, the Chugwater Group holds some of North America’s oldest known dinosaur fossils, including silesaurid femur and humerus fragments, challenging previous notions of dinosaurs’ early geographical confinement to the Southern Hemisphere.

As life slowly rebound, the Morrison Formation, approximately 150 million years old from the Jurassic Period, ushered in an era synonymous with colossal reptiles. Globally famous for its dinosaur fossils, this formation, exposed at Como Bluff near Medicine Bow and north of Thermopolis or Cody, reveals a Jurassic Wyoming that was warm and semi-arid, akin to a Mediterranean climate of today, albeit without the sea. Herbivores like stegosaurs, camarasaurs, apatosaurs, and diplodocus thrived alongside formidable carnivores such as allosaurs. While the popular "Jurassic Park" films often feature later Cretaceous species, the Morrison’s true inhabitants were a diverse and magnificent assemblage. Flowering plants had not yet evolved, but gymnosperms like ginkgo and cycads provided abundant sustenance for the massive plant-eaters. The fine-grained deposits of rivers and lakes within the Morrison Formation acted as natural traps, attracting thirsty creatures and preserving their remains. The dramatic demise of the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous Period, 66 million years ago, continues to fascinate, with theories ranging from a catastrophic asteroid impact (gaining traction during the Cold War’s nuclear anxieties) to emerging views that also incorporate massive greenhouse gas spikes from volcanic activity in India, underscoring the complex interplay of factors that can lead to ecosystem collapse.

The periods immediately preceding and following the dinosaur extinction are exceptionally well-preserved in Wyoming’s geological record, notably during an unusual tectonic episode known as the Laramide Orogeny. Over approximately 30 million years, this event thrust up the iconic mountain ranges that define the "Rockies" today – including the Bighorn, Wind River, Beartooth, Uinta, Granite, Laramie, and Front ranges. Uniquely, these mountains rose some 800 miles inland from the convergent plate boundary off the Pacific coast. This anomalous uplift is attributed to the shallow, difficult subduction of the Farallon oceanic plate, which, being unusually buoyant, scraped along the base of the North American plate until it encountered the ancient, rigid crustal roots beneath Wyoming, the very craton forged by the Sacawee Gneiss. Concurrent with this tectonic upheaval, seas ebbed and flowed, the asteroid struck, dinosaurs perished, and the world experienced the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) – a period of dramatic carbon dioxide concentration surge and abrupt global warming, which many Earth scientists consider a "distant mirror" for our own time.

The Green River Formation, dating to approximately 50 million years ago in the Eocene Epoch, offers a detailed record of the PETM’s aftermath. Its exquisite fossils of leaves, insects, fish, and amphibians, often preserving exceptional anatomical detail, are prized worldwide. Found at Fossil Butte National Monument, this formation also boasts freshwater stromatolites, echoing the microbial empires of the distant past. The Green River Formation accumulated as muddy sediment and organic matter at the bottom of a chain of ancient lakes, meticulously preserving the flora and fauna of its time. Eocene Wyoming was a subtropical, hot, and steamy environment, where palm trees and crocodilians thrived at latitudes now home to pine forests and grizzly bears – a powerful testament to the influence of greenhouse gases on climate. While the precise source of the immense volumes of hydrocarbons released during the PETM remains debated – possibilities include coal bed ignition by magmas or massive methane releases from the seafloor – the Green River Formation offers quantitative evidence. Its rare sodium bicarbonate minerals indicate atmospheric carbon dioxide levels exceeding 700 parts per million. This figure starkly contrasts with the conditions under which humans evolved, where CO2 concentrations never surpassed 350 ppm, and is considerably higher than our current 425 ppm, illustrating humanity’s accelerating trajectory towards ancient hothouse conditions. The profound irony is that the Green River Formation’s own coal seams and oil shale, formed from the lush ecosystems it preserves, are now being extracted, inadvertently contributing to a potential reenactment of its ancient climate reality. Yet, even as these lakes formed in the shadow of the rising Laramide mountains, erosion worked tirelessly, tearing down the peaks and accumulating thick sediment piles, eventually "unburying" these ancient rock formations, making them accessible to us today.

Finally, a mere 2.1 million years ago, during the Pleistocene Epoch, northwestern Wyoming experienced a series of cataclysmic volcanic eruptions as the region drifted over a mantle "hot spot." The Huckleberry Ridge Tuff, the youngest of these formations and the "yellow stone" of Yellowstone National Park, is the product of the first and largest of these "supervolcano" events. The eruption that created it sent an ash column 30 miles into the atmosphere, emptying a colossal magma chamber and leaving behind the vast Yellowstone caldera. The erupted volume, nearly 600 cubic miles, was followed by two more massive eruptions over the next 1.5 million years. While a recurrence, though statistically improbable in the short term, would indeed be catastrophic, potentially shutting down human activity across much of the continent, the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff, despite its destructive origins, offers a sobering perspective. As a silent witness to Earth’s last ice age and numerous climate oscillations, it expresses a profound concern not for its own potential future cataclysms, but for the rapidity of environmental changes observed over the last century – a poignant warning from a "supervillain" rock about humanity’s more immediate and self-inflicted concerns.

In listening to these ancient voices, from the primordial Sacawee Gneiss to the youthful Huckleberry Ridge Tuff, we encounter not merely inert geology, but a continuous, thrilling narrative of continental formation and fragmentation, oceanic transgressions and regressions, and the perennial rise and fall of ecosystems. These profound cycles of cataclysm and rebirth reveal a world ceaselessly remaking itself. Such narratives offer more than existential reassurance; they provide a crucial perspective on our current challenges. As humanity navigates broken systems and confronts discord and disillusionment, the deep time wisdom of these geological mentors reminds us that landscapes are not timeless but profoundly "timeful," offering enduring lessons in resilience, transformation, and the interconnectedness of all planetary processes. Those who truly understand the geological past are indeed blessed to repeat it, not in error, but with enlightened foresight.