Thirty years ago, in the summer of 1992, acclaimed novelist Jess Walter, then a staff writer for The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, found himself at the epicenter of a national drama: an armed standoff on an isolated mountaintop in northern Idaho. His direct, on-the-ground reporting chronicled the events that would become known as the Ruby Ridge standoff, a pivotal moment that profoundly shaped American discourse on liberty, government authority, and the fringes of societal dissent. The incident ignited when Randy Weaver, a man with deep ties to the Aryan Nations and fervent apocalyptic beliefs, failed to appear in court to answer charges stemming from the sale of a sawed-off shotgun. This led to a dramatic federal response, a siege that lasted eleven bloody days and tragically culminated in the deaths of Weaver’s wife, their son, and a U.S. Marshal. Ruby Ridge became a rallying cry for the burgeoning anti-government militia movement, its legacy continuing to cast a long shadow over contemporary political landscapes.

While the standoff inspired Walter’s sole work of nonfiction, Every Knee Shall Bow, now retitled Ruby Ridge, his latest novel, So Far Gone, delves into the enduring psychological and societal consequences of such foundational traumas. After three decades establishing himself as a best-selling and award-winning author of fiction, Walter returns to the themes that first propelled him into the national spotlight, exploring a nation grappling with its identity and the very definition of freedom in the wake of Ruby Ridge.

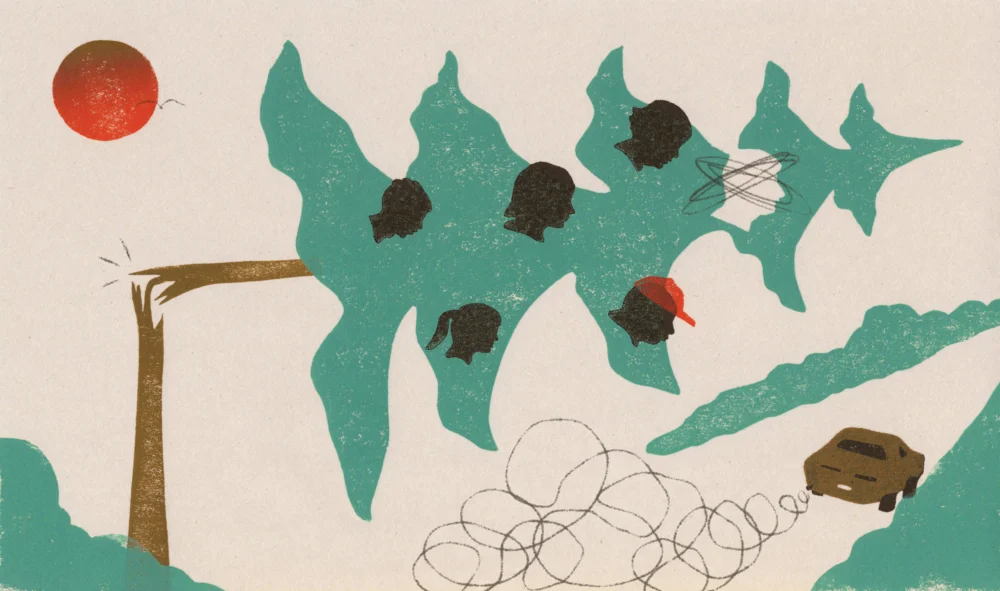

So Far Gone introduces readers to Rhys Kinnick, a divorced middle-aged man adrift in a sea of disillusionment. His son-in-law, Shane, has become consumed by a labyrinth of conspiracy theories, leaving Kinnick bewildered by his daughter’s continued allegiance. Facing his own professional displacement after a layoff and witnessing the election of Donald Trump, Kinnick retreats to an off-the-grid cabin, seeking solace from a world that feels increasingly alien. His self-imposed exile is disrupted when his grandchildren, whom he hasn’t seen in years, arrive with a disturbing revelation: their mother, Kinnick’s daughter, is missing, and Shane has vanished in search of her.

While not a direct fictional retelling of the Weaver family’s tragic saga, So Far Gone draws deeply from the milieu that birthed such events. Set in and around Walter’s native Spokane, the novel serves as a profound exploration of disillusionment and its far-reaching ramifications. "I think that disillusionment is one of the most human things that happens to us," Walter explained, "So, for Rhys to suddenly find himself the disillusioned one and feeling pushed out of society struck me as a great starting point for a novel."

Kinnick is not alone in his sense of alienation. His daughter grapples with understanding Shane, who finds a sense of belonging among well-armed religious separatists in Idaho. Walter himself admits to growing anxieties about the political climate, a sentiment crystallized by a stark screen time report on his own phone. "It informed me that I had been spending five and a half hours a day on my phone, doomscrolling," he confessed to High Country News. "I realized I couldn’t go on like this, imagining the demise of the country. I imagined myself going into a metaphoric woods to write the novel, turning my back on all of it."

Despite tackling weighty themes such as the proliferation of conspiracy theories and the rise of militia-affiliated churches, So Far Gone is imbued with Walter’s signature dark humor and a cast of quirky characters. In one memorable early scene, Kinnick bristles as Shane expounds on an elaborate conspiracy theory positing that the NFL’s most powerful figures are orchestrating global control through the sport. Later, a violent confrontation erupts over a set of brand-new truck tires, underscoring the absurdities that can escalate into tragedy. Walter believes this comic sensibility makes the narrative "in some ways more real, and that makes it more horrible." He elaborated, "People do get shot over things like tires. I believe so fully in the folly and fallibility of human beings; in many ways, it’s the only constant. So I don’t write humor as an effect; I write it as a philosophical underpinning of the world as I see it."

Over the three decades since he first bore witness to the anti-government fervor that coalesced at Ruby Ridge, Walter has observed the unsettling mainstreaming of what were once fringe conspiracy theories. "Now, we live in such a conspiracy-rich world," he remarked. "I don’t think Ruby Ridge was the cause of this so much as a harbinger of what was to come."

So Far Gone masterfully captures this contemporary moment, a period where many Americans grapple with a perceived loss of purpose amidst an increasingly polarized and fractured political landscape. The novel reflects a nation wrestling with its ideals of freedom and the nature of truth in an era of rampant misinformation.

In conjunction with his new novel, Walter is also revisiting his foundational work, Ruby Ridge. The book will receive its first update since 2008, including a new afterword that acknowledges the passing of Randy Weaver in 2022 and Gerry Spence, Weaver’s formidable attorney, who died in August. Walter is also undertaking a retrospective examination of the socio-political currents that have allowed anti-government sentiment to flourish in the American West since the Ruby Ridge incident. "Part of the update is looking at the way in which conspiracy theories have not only been absorbed into the mainstream, but have really become a winning political formula," he stated.

Despite the somber realities that have occupied his writing and his life for many years, Walter remains fundamentally hopeful. "My son calls me a toxic optimist because I am so optimistic in general," he shared. "I’m optimistic about human beings and their capacity for change and decency." This enduring optimism, coupled with his keen insight into the human condition, continues to inform his powerful storytelling.