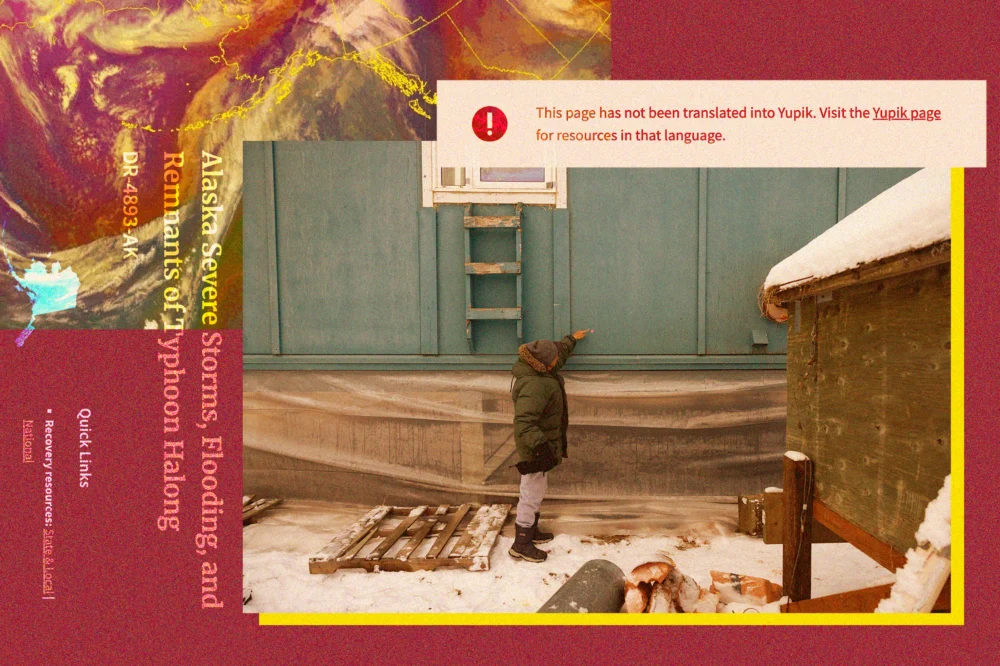

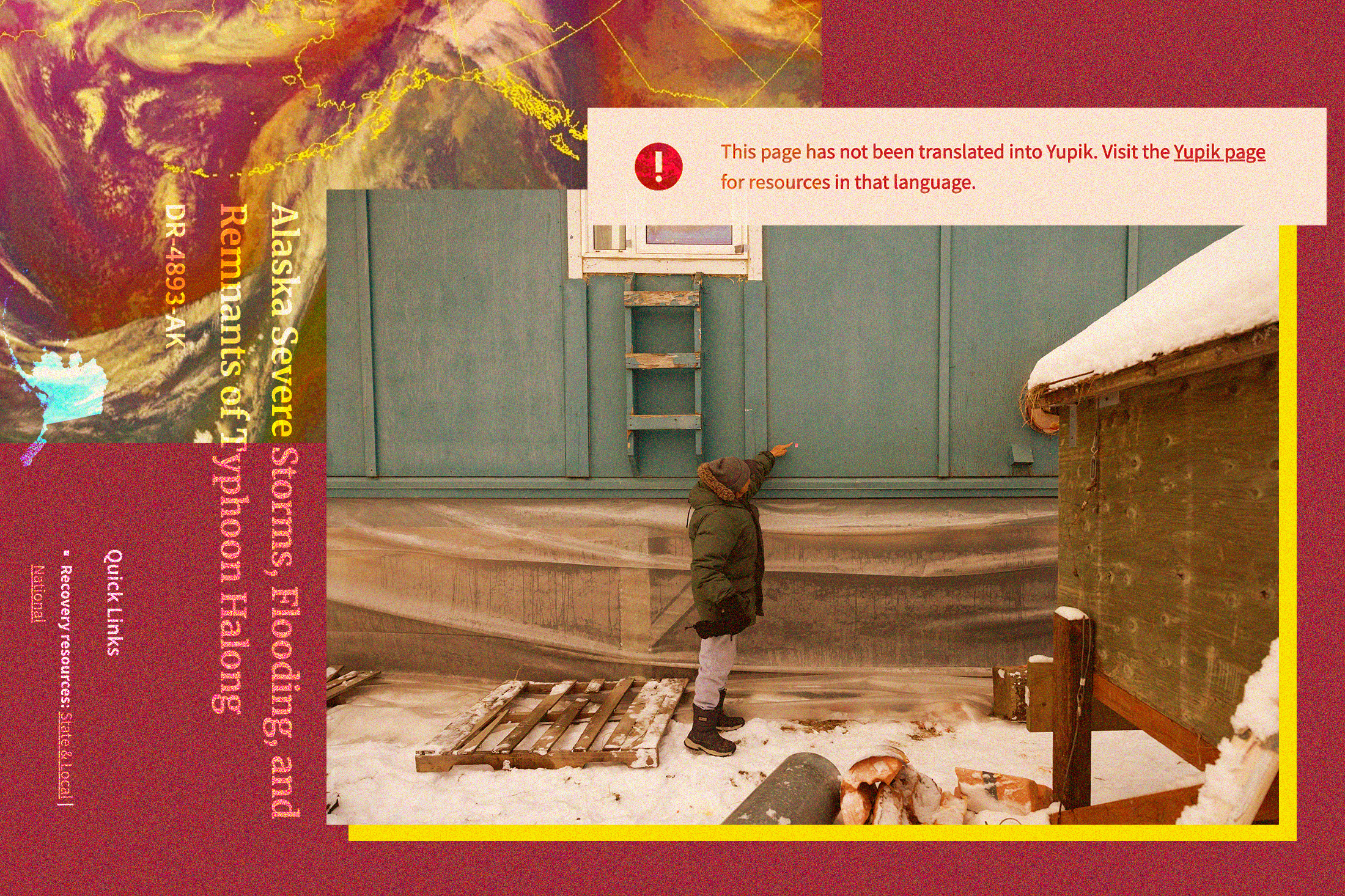

Julia Jimmie, a Yup’ik translator working with KYUK, expressed her profound disappointment, stating that the unintelligible materials made her believe "someone somewhere thought that nobody spoke or understood our language anymore." This egregious failure underscored a critical gap in federal disaster response: the profound neglect of linguistic and cultural nuances essential for effective communication with Indigenous populations. The incident led to Accent on Languages reimbursing FEMA for the faulty work, and the agency subsequently vowed to improve its practices, affirming that it would now employ "Alaska-based vendors" for Alaska Native languages, prioritizing those within disaster-impacted areas, and implementing a secondary quality-control review for all translations. Furthermore, FEMA asserted a commitment to continuous consultation with "Tribal partners" to ascertain and meet language service needs effectively.

Yet, as the region grapples with the aftermath of Typhoon Halong, which in mid-October displaced over 1,500 residents and claimed at least one life in the village of Kwigillingok, the specter of inadequate translation has re-emerged, this time centered on the burgeoning role of artificial intelligence. On October 21, the day before the Trump administration approved a disaster declaration for the storm, Prisma International, a Minneapolis-based company, posted an advertisement seeking "experienced, professional Translators and Interpreters" for Yup’ik, Iñupiaq, and other Alaska Native languages. Government records indicate Prisma has secured over 30 contracts with FEMA in recent years across various states, and its website prominently features a methodology that "combine[s] AI and human expertise to accelerate translation, simplify language access, and enhance communication across audiences, systems, and users." The job listing for Alaska Native language translators explicitly mentioned the requirement to "provide written translations using a Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) tool," signaling a clear intention to integrate AI into the translation workflow.

While a FEMA spokesperson in late October refrained from confirming a direct contract with Prisma for the Alaska response, the job posting’s preference for applicants with experience translating for "emergency management agencies, e.g. FEMA," and a connection to local Indigenous communities, strongly suggested an impending collaboration. Indeed, multiple Yup’ik language speakers in Alaska confirmed they had been approached by a company representative who identified Prisma as "a language services contractor for the Federal Emergency Management Agency." Julia Jimmie, among those contacted, expressed her willingness to translate for FEMA but harbored significant reservations about working with Prisma, particularly regarding its AI integration.

The expansion of artificial intelligence into critical sectors like translation has ignited both excitement and profound skepticism within Indigenous communities worldwide, not just in Alaska. While many Native tech and cultural experts recognize AI’s transformative potential, particularly for the revitalization and preservation of endangered languages, there are widespread warnings about its capacity to distort invaluable cultural knowledge and undermine fundamental language sovereignty. Morgan Gray, a member of the Chickasaw Nation and a research and policy analyst at Arizona State University’s American Indian Policy Institute, articulates this concern succinctly: "Artificial intelligence relies on data to function. One of the bigger risks is that if you’re not careful, your data can be used in a way that might not be consistent with your values as a tribal community."

The United States government currently lacks a comprehensive regulatory framework for AI, particularly concerning its use in sensitive contexts involving Indigenous data. However, the concept of "data sovereignty"—a tribal nation’s inherent right to define how its data is collected, used, and governed—is gaining significant traction in international dialogues surrounding Indigenous intellectual property. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples explicitly enshrines the principle of free, prior, and informed consent for the utilization of Indigenous cultural knowledge. UNESCO, the UN body responsible for cultural heritage, has specifically urged AI developers to respect tribal sovereignty when engaging with Indigenous communities’ data, recognizing the profound historical and ongoing vulnerabilities faced by these groups. Gray emphasizes the imperative for tribal nations to possess "complete information about the way that AI will be used, the type of tribal data that that AI system might use," stressing their right to sufficient time for consideration and the unequivocal right to refuse involvement, even in the face of ostensibly "altruistic motivation."

Despite these growing international norms and ethical considerations, it remains unclear whether Prisma has initiated direct consultations with tribal leadership in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. The Association of Village Council Presidents, a consortium representing 56 federally recognized tribes in the region, did not respond to inquiries for comment, leaving a critical communication gap. Prisma’s website indicates that clients can opt for human-only translation services and states that its AI usage is governed by an "AI Responsible Usage Policy." However, the specific details of this policy are not publicly accessible, and the company did not respond to requests for clarification, contributing to the opacity surrounding its practices.

FEMA’s internal policies regarding AI are similarly ambiguous. While the agency has demonstrated efforts to improve its engagement with Alaska Native communities since the 2022 translation debacle, a spokesperson’s email did not directly address questions about specific policies to regulate AI use or safeguard Indigenous data sovereignty. The response merely reiterated FEMA’s commitment to "works closely with tribal governments and partners to make sure our services and outreach are responsive to their needs," a general statement that falls short of outlining concrete protections against potential AI-related harms.

Prisma’s reach extends beyond Alaska, with government databases showing contracts with FEMA in over a dozen states and with other federal agencies. A case study highlighted on Prisma’s website showcases its "LexAI" technology, purportedly used to provide disaster relief information in more than 16 languages, including "rare Pacific Island dialects," following a wildfire. However, federal government records indicate this would be Prisma’s first engagement with the federal government specifically in Alaska.

For the Yup’ik language translators in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta contacted by Prisma, a fundamental and practical concern quickly emerged: the inherent capability of AI to accurately translate their intricate language. Julia Jimmie articulated this worry: "Yup’ik is a complex language. I think that AI would have problems translating Yup’ik. You have to know what you’re talking about in order to put the word together." Her concern is rooted in the linguistic realities of agglutinative languages like Yup’ik, where words are formed by adding multiple suffixes to a root, conveying complex meanings within a single word, a stark contrast to the more isolating morphology of English.

Most AI language models, particularly those reliant on statistical or neural network approaches, require vast datasets to achieve high levels of accuracy. Such extensive, well-curated data is exceedingly rare for Indigenous languages, which have historically been marginalized in digital spaces. Consequently, AI has a documented poor record when it comes to translating these languages, frequently producing inaccurate sentences, garbled syntax, and even entirely fabricated words. Sally Samson, a Yup’ik professor of Yup’ik language and culture at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, voiced deep skepticism that AI could master Yugtun syntax, which diverges substantially from English. Her apprehension extends beyond mere factual misinformation; she fears AI’s inability to convey the profound nuances of a Yup’ik worldview, where "Our language explains our culture, and our culture defines our language." Samson emphasizes that the respectful modes of communication among elders, co-workers, and friends are intrinsically shaped by deeply held cultural values, which AI, operating on statistical patterns rather than lived experience, is ill-equipped to replicate.

Recognizing these shortcomings, Indigenous software developers are actively pioneering their own AI solutions tailored to Native languages. These initiatives are often driven by a powerful desire to leverage technology for language preservation, empowering communities to take ownership of their linguistic future. Examples include an Anishinaabe roboticist who designed a robot to aid children in learning Anishinaabemowin, and a Choctaw computer scientist who developed a chatbot capable of conversing in Choctaw. The crucial distinction in these cases is that Indigenous people are not merely users, but the architects and decision-makers behind the AI models, ensuring that the technology aligns with their cultural values and community needs.

However, the introduction of AI by external private companies, particularly those contracting with federal agencies, raises significant concerns about potential exploitation. Crystal Hill-Pennington, who teaches Native law and business at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and provides legal consultation to Alaska tribes, worries about the implications if AI systems are trained on the intellectual labor of Indigenous translators for future commercial use by non-Native entities. "If we have communities that have a historical socioeconomic disadvantage, and then companies can come in, gather a little bit of information, and then try to capitalize on that knowledge without continuing to engage the originating community that holds that heritage, that’s problematic," she cautions.

Indigenous communities possess centuries of painful experience with outsiders extracting and exploiting their cultural knowledge. A stark recent precedent occurred in 2022 when the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council took the extraordinary step of banning a non-profit organization that had initially promised to aid in language preservation. After Lakota elders had spent years generously sharing their cultural knowledge, the organization controversially copyrighted the material and subsequently attempted to sell it back to tribal members in the form of textbooks. Hill-Pennington highlights how the integration of AI by private corporations introduces yet another layer of complexity to these already contentious discussions surrounding intellectual property rights. "The question is, who ends up owning the knowledge that they’re scraping?" she asks, pointing to the urgent need for clear ethical guidelines.

As AI technology rapidly evolves, so too are the global standards and expectations concerning its engagement with Indigenous cultural knowledge. Hill-Pennington acknowledges that some companies utilizing AI may still be unacquainted with the imperative of informed consent and the intricate concept of data sovereignty. Nevertheless, she stresses that these standards are becoming increasingly critical and undeniable. "Particularly if they’re going to be doing work with, let’s say, a federal agency that does fall under executive orders around authentic consultation with Indigenous peoples in the United States, then this is not something that should be overlooked," she concludes, emphasizing the profound responsibility that rests upon both government agencies and their contractors to ensure that technological advancements do not inadvertently perpetuate historical injustices or erode the linguistic and cultural foundations of Indigenous communities.