Winter’s embrace settles gently over the undulating topography of North Idaho, painting the bare limbs of aspens with a delicate glaze of snow that descends from a uniformly gray sky. This scene, however picturesque, embodies a profound ephemerality; the pristine blanket of white will likely yield to warmer temperatures within days, a stark contrast to the verdant landscape that only recently shed its autumn hues. Indeed, the very fabric of this immediate vista, from the fifteen-year-old aspen to the thirty-five-year-old window frame, exists within a fleeting temporal frame. Even the hill beneath the snow, composed of loess – fine, windblown silt deposited in the Palouse region periodically over the last two million years – represents but a flicker in the immense sweep of geological time, though it far predates the existence of humanity.

To grasp the staggering brevity of human presence on Earth, one might consider the compelling analogy offered by John McPhee in his seminal 1981 work, Basin and Range. McPhee invites us to extend our arms wide, imagining the distance from fingertip to fingertip as representing 4.5 billion years – the Earth’s venerable age. In this vast temporal expanse, the mere 300,000 years since Homo sapiens first emerged is so infinitesimally brief that, as he eloquently states, "in a single stroke with a medium-grained nail file you could eradicate human history." This profound illustration underscores our species’ recent arrival on a planet that has undergone unimaginable transformations across eons, shaping the very landscapes we inhabit and the forces that continue to sculpt our world.

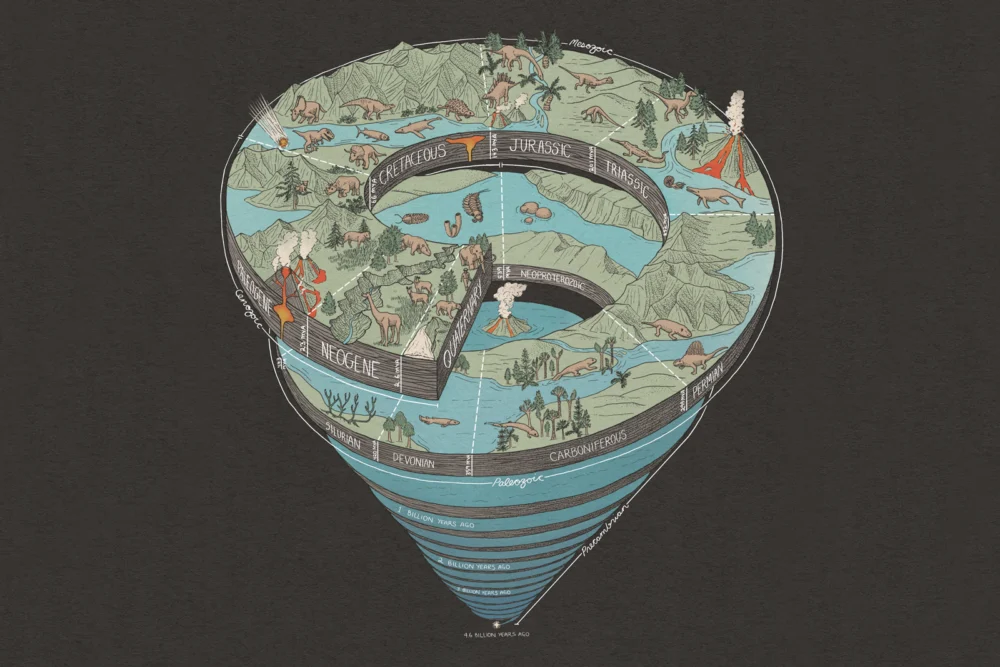

The Earth’s history is a grand narrative, divided by geologists into vast eons: the Hadean, Archean, Proterozoic, and Phanerozoic. For nearly four billion years, preceding the Cambrian explosion, simple life forms dominated an evolving planet, enduring colossal impacts, dramatic atmospheric shifts, and the slow dance of continental drift. The loess deposits of the Palouse, for instance, are a testament to the powerful glaciofluvial processes of the Pleistocene epoch, when continental ice sheets repeatedly advanced and retreated, pulverizing rock and unleashing torrents of meltwater that carved the region’s distinctive coulees and deposited these fertile silts. These processes, unfolding over millions of years, not only shaped the land but also influenced the patterns of life, creating the ecological foundations upon which subsequent ecosystems, and eventually human societies, would thrive.

Stepping beyond the immediate and the merely historical, a deeper appreciation for "deep time" allows us to explore what the American West was like thousands, millions, and even billions of years ago, revealing how this ancient history remains vividly visible and profoundly consequential today. The West, a region characterized by its dramatic geological diversity and active tectonic processes, serves as an unparalleled natural laboratory for this endeavor. Its towering mountain ranges, vast deserts, and iconic canyons expose an intricate stratigraphic record, offering a tangible connection to the planet’s formative eras.

Wyoming, in particular, stands as a cornerstone for understanding Earth’s infancy, boasting some of the oldest rock exposed at the planet’s surface in the Western U.S.: the 3.45 billion-year-old Sacawee gneiss. This ancient metamorphic rock, part of the Wyoming Craton, represents a fragment of Earth’s primordial continental crust, formed during the Archean Eon when the planet was a vastly different place. In that epoch, Earth’s atmosphere was largely anoxic, primitive oceans covered much of its surface, and microbial life, such as stromatolites, began to proliferate, slowly oxygenating the atmosphere over billions of years. Studying such ancient formations provides critical insights into the very mechanisms of continental assembly and the early conditions that fostered life, connecting the present-day landscape of Wyoming to the planet’s earliest geological chapters.

Further south, the majestic Grand Canyon offers another unparalleled window into deep time. Its mile-deep chasm, carved primarily by the Colorado River, exposes nearly two billion years of geological history, layer upon magnificent layer. From the ancient Vishnu Schist and Zoroaster Granite at its base to the more recent Cenozoic formations at its rim, the canyon’s strata tell a story of ancient seas, vast deserts, volcanic eruptions, and immense tectonic uplift. Ongoing scientific investigations continue to refine our understanding of its complex formation, challenging previous assumptions and offering fresh perspectives on the interplay of erosion, uplift, and climate over geological timescales. These new insights not only enrich our knowledge of a natural wonder but also inform broader debates about geological processes and landscape evolution globally.

The endurance of species also offers a powerful lens through which to view deep time. The pronghorn, often mistakenly called the American antelope, represents a remarkable lineage that survived the dramatic climatic shifts and megafauna extinctions of the Pleistocene epoch. Evolving on the North American plains, the pronghorn developed incredible speed, a trait believed to be an adaptation for evading now-extinct predators like the American cheetah. Its survival through successive ice ages, a period marked by vast sheets of ice covering much of the continent and significant ecological restructuring, highlights the resilience and adaptability of life in the face of profound environmental change. Understanding the pronghorn’s evolutionary journey provides crucial context for contemporary conservation efforts, reminding us of the deep historical roots of today’s ecosystems.

Equally compelling is the scientific journey to comprehend plate tectonics, a revolutionary theory that fundamentally reshaped our understanding of Earth’s dynamic nature. The concept, initially met with skepticism, gained widespread acceptance as evidence from seafloor spreading, paleomagnetism, and seismic activity accumulated. This scientific odyssey, spanning decades, illustrates how meticulous observation, rigorous data analysis, and intellectual courage allow humanity to decipher the colossal forces that have ceaselessly reshaped continents, raised mountains, and fueled volcanic activity for billions of years. The active tectonics of the American West, from the San Andreas Fault to the Yellowstone caldera, are direct manifestations of these ongoing planetary processes, constantly reminding us of the Earth’s restless interior.

This journey into deep time serves as a vital invitation to pause, to step away from the relentless churn of daily headlines, seasonal fluctuations, and electoral cycles. It encourages a shift in perspective, prompting us to consider the forces and phenomena that have shaped our world over scales far exceeding human experience. By widening our focus beyond the immediate scope of human endeavors, we can cultivate a deeper understanding of the West, appreciating its landscapes not merely as scenic backdrops but as living testaments to billions of years of geological and biological evolution.

Even as our species confronts unprecedented ecological and climatic chaos, profoundly impacting the planet’s systems, Earth will undoubtedly continue its grand cycle of transformation and renewal, just as it has for eons. The concept of deep time offers a sobering humility regarding our place in the cosmic order, yet also imbues a profound sense of responsibility for our brief, impactful tenure. Our aim in exploring this deep past is not only to celebrate the planet’s enduring grandeur but, implicitly, to acknowledge the deep and wide-open future of the West, a future that will continue to be written by both human actions and the inexorable, slow-burning forces of the Earth itself.