A quiet bureaucratic conflict in late 2019 escalated into a national debate over the political influence wielded by ranchers on federal land management, revealing a systemic challenge to environmental stewardship in the American West. The dispute began when two Montana ranchers, operating under a federal grazing permit, faced scrutiny from the U.S. Forest Service. Agency staff documented repeated violations, including cattle found in unauthorized areas, dilapidated fences, and salt licks positioned too close to sensitive creeks and springs, drawing livestock into vital riparian habitats. These infractions, observed four times during September alone, prompted the Forest Service to issue a "notice of noncompliance," asserting a "willful and intentional violation" and warning of potential permit revocation. Despite the ranchers’ relatively modest scale within the vast landscape of public lands grazing, which accounts for one of the largest land uses in many Western states like Montana, where cattle often outnumber human residents, their case quickly attracted powerful allies.

The ranchers, contending they were unfairly targeted, argued in a communication to the agency that "The Forest Service needs to work with us and understand that grazing on the Forest is not black and white." Conversely, the acting district ranger maintained that his staff had "gone above and beyond" to facilitate compliance. This local disagreement soon transcended its administrative boundaries. Assisted by a former Forest Service employee, the ranchers contacted their congressional representatives in early 2020. Staffers for then-Representative Greg Gianforte and Senator Steve Daines, both Republicans representing Montana, promptly intervened, initiating over a year of persistent correspondence and engagement with Forest Service officials. This intervention prompted one exasperated Forest Service official to remark in a 2021 email to colleagues that ranchers, upon hearing something they disliked, would simply "run to the forest supervisor and the senator’s office to get what they want."

This episode highlights a broader pattern across the American West, where federal land management agencies like the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) frequently encounter political pressure when attempting to enforce grazing regulations. Ranchers cited for violations or those resisting environmental rules often enlist a network of pro-grazing lawyers, industry trade group lobbyists, and sympathetic politicians ranging from local county commissioners to state legislators and U.S. senators. Many of these allies, some of whom have ascended to influential positions within recent administrations, advocate for looser environmental regulations and reduced accountability for permit holders who break the rules. Current and former federal employees attest to the significant impediment this political leverage poses to consistent enforcement. A BLM employee, speaking anonymously due to fear of retaliation, articulated the pervasive sentiment: "If we do anything anti-grazing, there’s at least a decent chance of politicians being involved. We want to avoid that, so we don’t do anything that would bring that about."

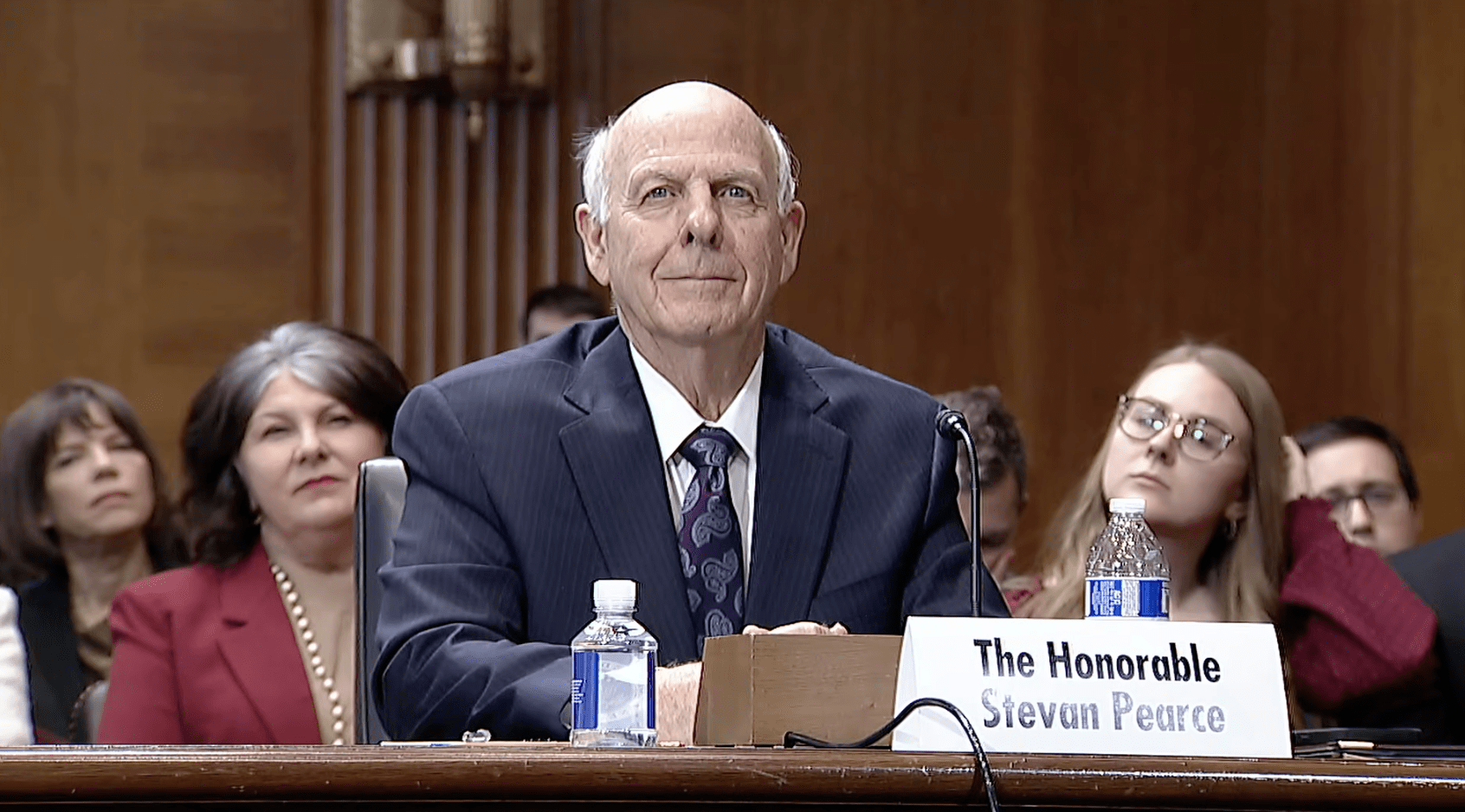

Mary Jo Rugwell, a former director of the BLM’s Wyoming state office, acknowledged that while most public-lands ranchers adhere to regulations, a segment is "truly problematic," deliberately flouting rules and leveraging political connections to circumvent enforcement. Public records reveal over 20 communications from members of Congress to the BLM and Forest Service regarding grazing issues since 2020, addressing matters such as "Request for Flexibility with Grazing Permits" and "Public Lands Rule Impact on Ranchers and Rural Communities." These lawmakers include a bipartisan group of figures such as Rep. Paul Gosar (R-Ariz.), former Rep. Yvette Herrell (R-N.M.), former Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), and Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah), illustrating the widespread nature of this advocacy. Rick Danvir, a former wildlife manager on a large Utah ranch, also noted that federal agencies are caught between ranchers and litigious environmental organizations, often adopting a defensive posture to avoid costly legal battles.

The sustained intervention from Senator Daines’ office in the Montana case, which included demands for detailed information and an unannounced visit by a staffer to a meeting between the ranchers and the Forest Service, clearly influenced the agency’s approach. While constituent services are a legitimate function of elected officials, local Forest Service personnel perceived the external political pressure as leading to preferential treatment for the ranchers. One official lamented in 2020, "If this issue was solely between the (ranger district) and the permittee, we should administer the permit and end the discussion there. Unfortunately, we have regional, state and national oversight from others that deters us from administering the permit like we would for others." Another expressed the demoralizing effect of being "expected to hold all other permittees to the terms of their permits/forest plan/forest handbook … yet be told to continually let it go with another." By June 2020, the acting district ranger was willing to "cut (the ranchers) some slack." Despite repeated findings of permit violations, including evidence of overgrazing that threatened vegetation and soil health in December 2020 and for four consecutive years by late 2022, the Forest Service refrained from issuing further formal notices of noncompliance, wary of the inevitable conflict. The agency’s year-end report for 2022 notably declined to recommend another citation, confirming that "the drama continues," as one official aptly put it. A spokesperson for Senator Daines affirmed his office’s commitment to advocating for constituents, while the Forest Service, the ranchers, and Gianforte’s office did not comment.

The current administration has positioned itself as a significant ally for ranchers seeking to roll back perceived government overreach. This stance is evident in key appointments and policy shifts. Karen Budd-Falen, a self-described "cowboy lawyer" with a history of suing the federal government over grazing regulations – including a notable RICO lawsuit against individual BLM staffers that reached the Supreme Court – was appointed to a high-level position at the U.S. Department of the Interior. Her background, stemming from a prominent ranching family and holding a stake in a large Wyoming cattle ranch, underscores the administration’s alignment with ranching interests. Similarly, President Donald Trump nominated Michael Boren, a tech entrepreneur and rancher with a contentious history with the Forest Service, to oversee the agency as Undersecretary of Agriculture for Natural Resources and Environment. Boren had previously faced a cease-and-desist letter from the Forest Service for allegedly clearing national forest land and building a private cabin on it.

The administration has moved swiftly to dismantle Biden-era environmental reforms. In September, it proposed rescinding the Public Lands Rule, which had been finalized in May 2024 to elevate the protection and restoration of wildlife habitat and clean water to equal footing with economic uses like oil drilling, mining, and grazing on federal lands. This rule would have introduced conservation leasing and strengthened environmental impact analyses for grazing. Concurrently, a Biden-era BLM memo prioritizing environmental review for degraded grazing lands and sensitive wildlife habitats was effectively nullified this year. The Interior Department and BLM stated that policy decisions aim to "balance economic opportunity with conservation responsibilities," but critics argue these actions tilt the balance away from environmental protection.

Furthermore, the administration has initiated a broad effort to open 24 million acres of "vacant" federal grazing lands to ranchers, framing "grazing as a central element of federal land management." Many of these allotments were previously unused due to ecological reasons such as wildfire recovery, insufficient forage or water, or the presence of invasive species. Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz issued a directive in May, giving staff approximately two weeks to identify unused allotments suitable for quick repopulation with livestock, a policy that aligns with the Public Lands Council’s call for agencies to swiftly fill vacant allotments. While a USDA spokesperson maintained that "vacant grazing allotments have always been open and available to permitted grazing," the accelerated push signals a clear shift in priority.

Historical precedent demonstrates the intense pushback against attempts to strengthen grazing regulations. In the mid-1990s, the Clinton administration retreated from a proposal to raise grazing fees amidst widespread opposition from public-lands ranchers and their Republican allies, who viewed the reforms as an existential threat to their livelihoods. As one rancher at a hearing on the failed proposal declared, "The government is trying to take our livelihood, our rights and our dignity. We can’t live with it."

While the ranching industry’s lobbying expenditures do not rival those of major sectors like pharmaceuticals or oil and gas, their influence in Washington, D.C., remains significant. J.R. Simplot Co., the largest holder of BLM grazing permits, spent approximately $610,000 lobbying Congress between 2020 and 2025 and recently hired the Bernhardt Group, founded by former Trump Interior Secretary David Bernhardt. Trade groups like the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA), with affiliates in 40 states, have spent nearly $2 million lobbying over the past five years and contributed over $2 million to federal candidates, with more than 90% of their 2024 contributions going to Republicans. The NCBA has actively challenged Biden-era environmental regulations, including lawsuits against the EPA over water rules and the Interior Department over endangered species protections for the lesser prairie chicken. The association vociferously opposed the Public Lands Rule, filing a lawsuit to halt its implementation, with its then-president, Mark Eisele, calling it "a stepping stone to removing livestock grazing from our nation’s public lands." Nada Culver, a former BLM deputy director during the Biden administration, noted that ranchers’ political influence extends beyond financial contributions, rooted deeply in their "cultural power" as "icons of the American West."

This influence also manifests at the state and local levels, where officials often rally behind ranchers facing federal enforcement. In a long-running dispute in Utah’s Fishlake National Forest in 2019, a rancher reportedly threatened a Forest Service supervisor, implying harm to his family if regulations were enforced. This incident echoes the infamous 2014 Bundy standoff in Bunkerville, Nevada, where rancher Cliven Bundy, owing approximately $1 million in grazing fines and unpaid fees for two decades of chronic trespassing, engaged in an armed confrontation with federal agents. Local officials, including the Nye County Commission and state legislators, openly supported Bundy, with the county sheriff even expressing willingness to jail Forest Service personnel. The Bundy family’s political ties have strengthened further, with Cliven Bundy’s niece, Celeste Maloy, elected to represent Utah’s 2nd Congressional District in 2023. Maloy has since advocated for selling federal lands and easing ranchers’ access to vacant grazing allotments, receiving $20,000 in campaign contributions from the NCBA during the 2024 election cycle.

Wayne Werkmeister, a retired BLM employee with decades of experience overseeing federal grazing lands, recounts the immense difficulty of enforcing public-lands protections. In a case near Grand Junction, Colorado, he and his colleagues spent years documenting habitat damage across a 90,000-acre allotment due to roughly 500 cattle. When Werkmeister pushed to reduce cattle numbers, the ranchers hired former BLM employees to accuse the agency of "agenda driven bullying" and copied then-U.S. Senator Cory Gardner, a Colorado Republican, on their correspondence. The Budd-Falen Law Offices also intervened, warning that reducing grazing could "unnecessarily force them out of business." Werkmeister’s superiors then ordered him to gather more data, despite years of existing documentation. Ultimately, he was unable to sufficiently reduce grazing, and the allotment was reapproved for grazing as recently as 2024. Werkmeister considers this a major failure, observing the degraded landscape now dominated by invasive cheatgrass: "Overgrazed to the point of gone." This ongoing struggle underscores the deep-seated challenges federal land managers face in balancing economic interests with environmental stewardship amidst a potent landscape of political and cultural influence.