Montana, a landscape that first captured the imagination during high school years, represented an ideal of remoteness, untamed natural beauty, and boundless adventure. It was a place envisioned as an escape from the pressures of urban professional life, a sanctuary where one could exist without the societal expectation of becoming a lawyer or banker, and crucially, without feeling any shame for not conforming to those paths. The profound sense of solitude possible in such a setting, the ability to be alone without experiencing loneliness, was a powerful draw. This yearning for the wide-open spaces of the American West, and specifically Montana, took root in 1985, a time when such seemingly untouched expanses still felt accessible.

The first physical encounter with Montana occurred in 1997 during a summer road trip from Chicago, undertaken to find rental housing for graduate studies in Missoula. The visual clarity of the state was striking: the air was crystalline, the sky an expansive cerulean, and the rivers ran with pristine purity. Each passing hillside evoked an almost irresistible urge to stop the car and ascend, to immerse oneself in the grandeur. It was during this period that the unique character of Montana began to reveal itself through its peculiarities. Upon arriving, a notable absence was a daytime speed limit on highways, a stark contrast to the more regulated roads of other states. Montana had only temporarily adopted a speed limit in the 1970s, a measure mandated by the federal government during the energy crisis, and even then, the state managed to circumvent its full imposition. While occasional speed limit signs were posted, they were largely ignored by drivers, and law enforcement’s approach was equally distinctive. Instead of issuing tickets for "speeding," citations were framed as "wasting fuel," and remarkably, the penalty for such infractions, regardless of the velocity achieved (unless deemed reckless), was a mere five dollars.

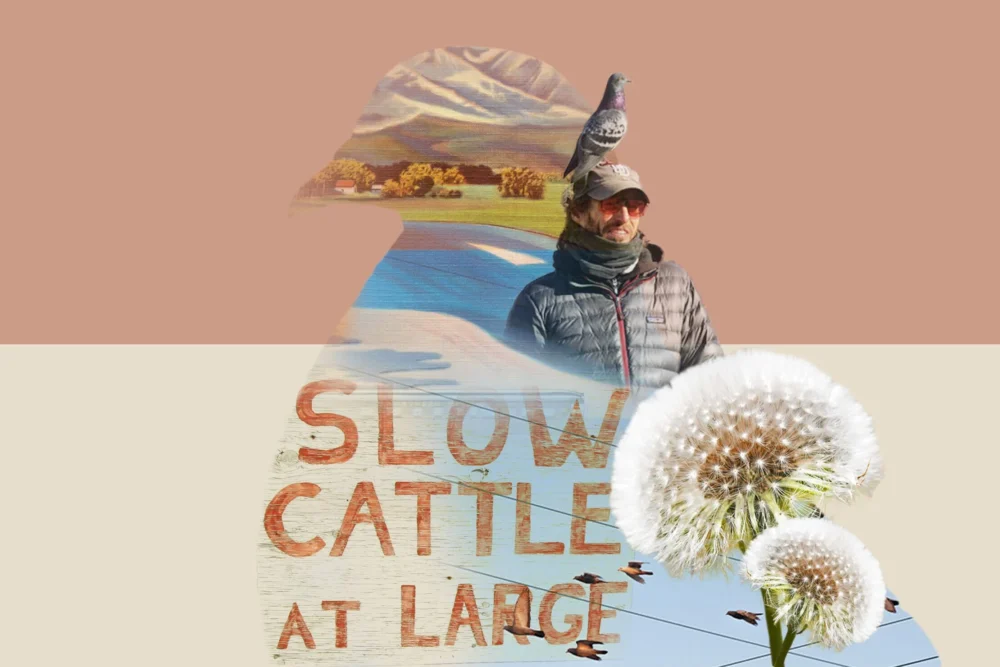

One of the early discoveries that brought a unique thrill was encountering a "CATTLE AT LARGE" sign. Until that moment, the term "at large" had been solely associated with criminals and escaped convicts. This sign offered a new perspective on the bovine inhabitants of the landscape, prompting a contemplation of their presence. Were they simply placidly grazing by the roadside, or were they harboring deeper thoughts and intentions behind those large, dark eyes? The author vividly recalls a drive on a secluded back road at fifty miles per hour when, rounding a bend, the "CATTLE AT LARGE" sign served as a crucial warning. The instruction to slow down proved prescient, as a substantial shadow loomed ahead—a large cow lying directly in the path, a hazard that might have been met head-on without the timely alert.

The phrase "at large" fundamentally means "with great liberty" or, in essence, possessing an ample expanse for movement and roaming. This concept resonates deeply with the spirit of characters in Bruce Springsteen’s music, individuals seeking freedom and unrestricted movement. Montana’s "CATTLE AT LARGE" signs are a direct manifestation of this reality: a state characterized by vast ranches where fences are sparse, and drivers might encounter thousands of pounds of livestock unexpectedly occupying the roadway, with no apparent urgency to yield. This untamed presence of nature, the blurring of boundaries between human and animal domains, mirrors a domestic situation developing in the author’s own home, which has become, in effect, a "Pigeonopolis" filled with pigeons "at large," where the distinction between the human world and the natural world has dissolved.

Among the avian residents, one young pigeon exhibits a distinctive gait, a spraddle-legged stance evident even from its fledgling days. Its left leg consistently trailed behind, causing the hip joint to turn outward. Initial attempts to manage this condition involved tying the bird’s legs together, an unsuccessful endeavor. The solution evolved to using specialized tags—plastic cuffs clipped just below the knee—to which strands of yarn were attached. This makeshift support system aimed to prevent the legs from spreading too far apart while minimizing irritation to the bird’s underside. After a few weeks of this treatment, during which the pigeon progressed to juvenile status, the cuffs were removed. The bird regained a semblance of normal posture, with its feet mostly positioned beneath it. However, within days, the leg reverted to its splayed position, and the hip joint resumed its unnatural orientation. Despite this physical challenge, the pigeon’s persistent efforts to behave like a "normal" bird have endeared it as a particular favorite. It often occupies the living room floor, directly in the path of the kitchen doorway, its chosen spot despite the frequent passage of its human caretaker. Each encounter elicits a momentary startle response, yet the bird remains steadfastly in its preferred location.

Within a hearthside cabinet resides another juvenile pigeon, brought in by neighbors, with a broken wing. Additionally, a third juvenile inhabits the living room, the offspring of a caged female and a "bully" male pigeon who nests on the porch in a box initially intended for Two-Step, the author’s first pigeon, and his partner V. The parentage of this "beautiful bastard child" is unmistakable; it bears no resemblance to its mother or her mate but is the spitting image of the bully pigeon. This suggests a clandestine encounter occurred months prior when the cage was temporarily placed on the porch, allowing the flightless couple supervised outdoor time. During this period, the female apparently engaged in a brief, yet consequential, liaison with the visiting male. Remarkably, her mate remains devoted, their bond evident in their synchronized actions. When released, they move together, mirroring each other’s foraging for dandelion leaves, and within the cage, they huddle closely, wing to wing. This newly arrived juvenile now navigates the living room, "at large," seeking a comfortable spot on the floor to settle.

This constant activity with the pigeons serves as a welcome distraction, particularly as the author also identifies as "disabled," at least by legal standards. The experience is profoundly meditative and offers solace for persistent headaches. At certain times of the day, the pigeons engage in synchronized preening, their rhythmic feather-flicking creating a soothing soundscape that fills the room. Two-Step and V. occupy their nesting box beside the author, positioned near a window to absorb warmth radiating from the house. Closing the blinds creates a more nocturnal ambiance, encouraging them to adhere to natural sleep cycles. The author anticipates soon following suit, seeking rest and finding refuge in dreams where all inhabitants, human and avian, can feel safe.

Currently, twelve birds inhabit the house, either flying freely or walking about. Despite efforts to foster a sense of wildness, they are gradually becoming more accustomed to human presence. The hope is that upon their release in the spring, they will swiftly reacquaint themselves with natural caution towards creatures resembling humans. The birds have begun to assert their presence, gradually encroaching on personal space. At one point the previous evening, two were perched on the back of the couch, one occupied a cardboard box nearby, another sat atop a small artificial Christmas tree, and one, emboldened by the author’s legs being propped on the coffee table, stood on his toes and then ambled up his leg. The scene, by the author’s account, resembled a character from a Disney cartoon. Any sudden movement or unexpected sound, like a sneeze, would likely trigger a chaotic flurry of flight and feathers. However, there was no impetus to move; the author remained still, akin to a statue in a park adorned with pigeons. The intricate details of their spread pink toes and the peculiar gait of the bird ascending his leg were observed with fascination, noting the golden flecks surrounding its eye.

The author finds joy in whatever brings happiness to the birds and harbors a deep affection for these creatures, grateful for the solace they provide against feelings of loneliness. This role as their "shepherd" offers a vital sense of purpose. As understanding of their behavior grows, so too does the ability to act in ways that are less intimidating to them, fostering a sense of security. On most days, interactions with birds far exceed those with people. Aside from occasional hugs or fist bumps, human contact has been scarce for an extended period. Yet, the gentle touch of a bird standing on toes, the act of picking up younglings for cage cleaning, or giving Two-Step a bath provide a profound sense of connection. During the quiet hours spent on the couch, a recurring thought emerges: "I am becoming bird." There is a hopeful anticipation that soon, a deeper understanding of avian communication will dawn, perhaps leading to greeting each day with contented "chukking" sounds to a newfound partner, and later, in the warmth of the sun, soaring together to perch on telephone wires, surveying the rolling green hills of Montana that emerge from the distant treetops.

This essay is excerpted with permission from We Should All Be Birds by Brian Buckbee with Carol Ann Fitzgerald, published by Tin House in 2025. Copyright © 2025 by Brian Buckbee and Carol Ann Fitzgerald.