Winter’s embrace has settled over the undulating terrain of North Idaho, painting the bare limbs of aspens with a delicate layer of snow, as pristine flakes drift from a monochromatic sky. This picturesque scene, while a vivid present reality, is inherently fleeting; the soft blanket of white will likely yield to warmer temperatures within days or weeks, a testament to nature’s ceaseless cycles. Just a few days prior, the landscape awaited its inaugural snowfall, underscoring the rapid transition of seasons and the impermanence of our immediate surroundings. Indeed, a contemplative gaze reveals that nearly everything within view—from the fifteen-year-old aspen reaching for the sky, to the windowpane installed three and a half decades ago—exists within a relatively brief temporal frame. Beneath the temporary snow lies a hill composed of loess, a fine silt deposited across the Palouse region by winds over the last two million years. This geological span, while immense by human standards, represents but a momentary flicker in the grand narrative of Earth’s existence, predating humanity’s emergence by a significant margin.

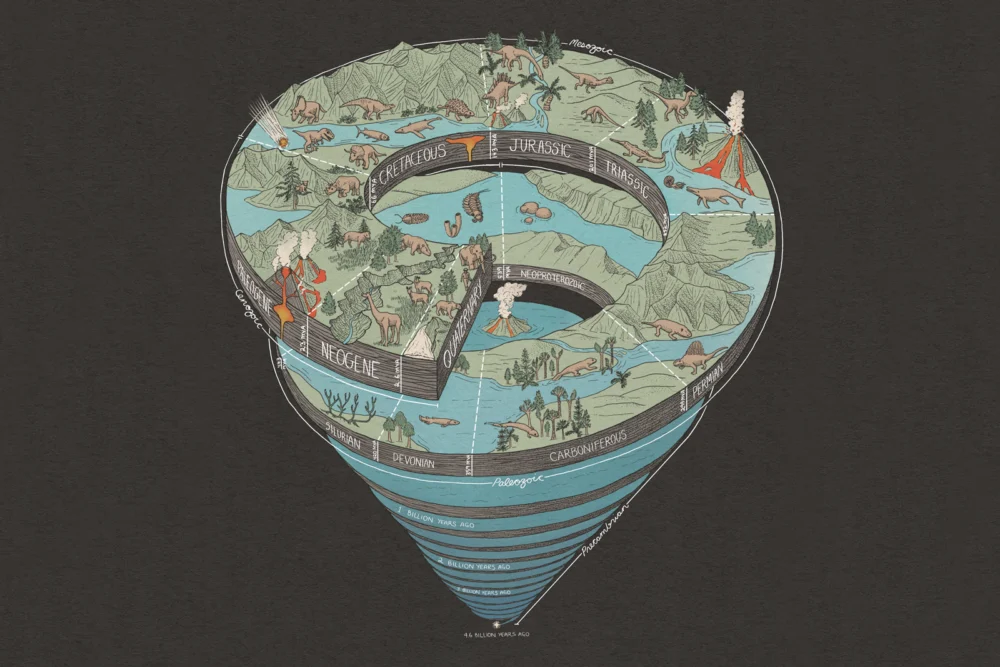

To truly grasp the astonishing brevity of human history against the backdrop of planetary time, the renowned author John McPhee, in his seminal 1981 work Basin and Range, offered a compelling analogy. He suggested extending one’s arms wide, imagining the span from fingertip to fingertip as representing 4.5 billion years—the venerable age of our planet. In this colossal scale, the approximately 300,000 years since Homo sapiens evolved appears infinitesimally small, so minuscule, in fact, that McPhee eloquently stated, "in a single stroke with a medium-grained nail file you could eradicate human history." This profound visualization serves as a powerful invitation to transcend the immediate, the daily, and even the generational, to consider the forces and phenomena that have sculpted our world over unfathomably longer periods.

Embracing this "deep time" perspective offers a crucial lens through which to examine the American West, exploring its ancient past stretching back thousands, millions, and even billions of years, and understanding how this profound history remains palpably visible and profoundly consequential today. Such an exploration transcends the ephemeral concerns of daily news cycles, inviting a deeper appreciation for the Earth’s enduring processes. For instance, the majestic landscapes of Wyoming harbor some of the planet’s most ancient exposed rock: the 3.45 billion-year-old Sacawee gneiss. This metamorphic rock, formed under immense heat and pressure deep within the Earth’s crust, offers a tangible link to the Hadean and Archean eons, periods when the Earth’s crust was just beginning to stabilize, continents were nascent, and the earliest forms of life were potentially emerging in primordial oceans. Studying such ancient geological formations provides invaluable insights into the planet’s fundamental building blocks and the colossal forces that shaped its early architecture. These ancient cratons, the stable cores of continents, demonstrate the incredible resilience and persistence of geological structures over eons, influencing everything from mineral distribution to seismic activity.

Further journeys into deep time reveal the intricate stories etched into other iconic Western landscapes. The Grand Canyon, for example, stands as a monumental testament to the relentless power of erosion and uplift. Its layered strata expose billions of years of geological history, meticulously carved by the Colorado River over millions of years, revealing ancient oceans, deserts, and mountain ranges long vanished. Each layer, a chapter in Earth’s autobiography, holds clues to past climates, ecosystems, and tectonic events that have continuously reshaped the region. Understanding the Grand Canyon’s formation necessitates comprehending the slow, inexorable forces of plate tectonics—the grand mechanism by which Earth’s lithosphere is constantly in motion, driving continental drift, mountain building, and volcanic activity, a scientific paradigm that revolutionized geology and continues to deepen our understanding of planetary dynamics.

The deep past also illuminates the remarkable resilience and evolutionary ingenuity of life. The American pronghorn, often mistaken for an antelope, stands as a living relic of the Pleistocene epoch, the geological period characterized by dramatic glacial cycles and megafauna. Its unparalleled speed and endurance, making it the fastest land animal in North America, are not merely adaptations to its current environment but are thought to be the evolutionary legacy of a time when it outran formidable predators like the now-extinct American cheetah. The pronghorn’s continued existence is a vivid reminder of the dynamic interplay between species and their ever-changing environments, a testament to the long evolutionary arms races that have shaped the biodiversity we observe today.

This journey into deep time, therefore, is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental reorientation of perspective. It prompts a reconsideration of humanity’s role and impact on a planet that has endured, transformed, and remade itself countless times over billions of years. While human enterprises, particularly in recent centuries, have indeed spurred significant ecological and climatic chaos, contributing to unprecedented rates of species extinction and global warming, Earth’s geological clock operates on scales that dwarf even our most profound disturbances. The planet will continue to evolve, its tectonic plates shifting, its climate oscillating, and its life forms adapting, long after the echoes of human civilization fade.

By widening our focus beyond the immediate scope of human endeavors and embracing the concept of deep time, we can cultivate a more profound understanding and respect for the intricate, long-running processes that govern our world. It fosters humility and encourages a more sustainable stewardship, recognizing that our actions, though impactful in the short term, are but a single, fleeting chapter in an ongoing saga. This holistic perspective celebrates the deep past—the immense, unimaginable stretches of time that shaped the very ground beneath our feet and the air we breathe—and implicitly acknowledges the deep and wide-open future of the West, a future that will continue to unfold with or without human presence, driven by the planet’s own inexorable forces. It is an invitation to witness the enduring grandeur of geological and evolutionary processes, offering not just knowledge, but a profound sense of connection to the Earth’s enduring narrative.