The profound narrative of Earth’s history, stretching back billions of years, often feels abstract, yet in the rugged landscapes of Wyoming, this epic saga is etched in stone, offering tangible connections to our planet’s tumultuous past. For centuries, humanity has sought solace and wisdom from ancient sentinels like gnarled trees, whose rings silently chronicle eras of crisis and resilience, reminding us of the transient nature of our present moment. However, for a truly grand perspective, one must delve deeper, listening to the oldest ancestors of all: the rocks beneath our feet, which, despite their taciturn reputation, continuously impart their profound memories of Earth’s transformations, serving as a powerful form of "Natural Intelligence" in an age captivated by artificial counterparts.

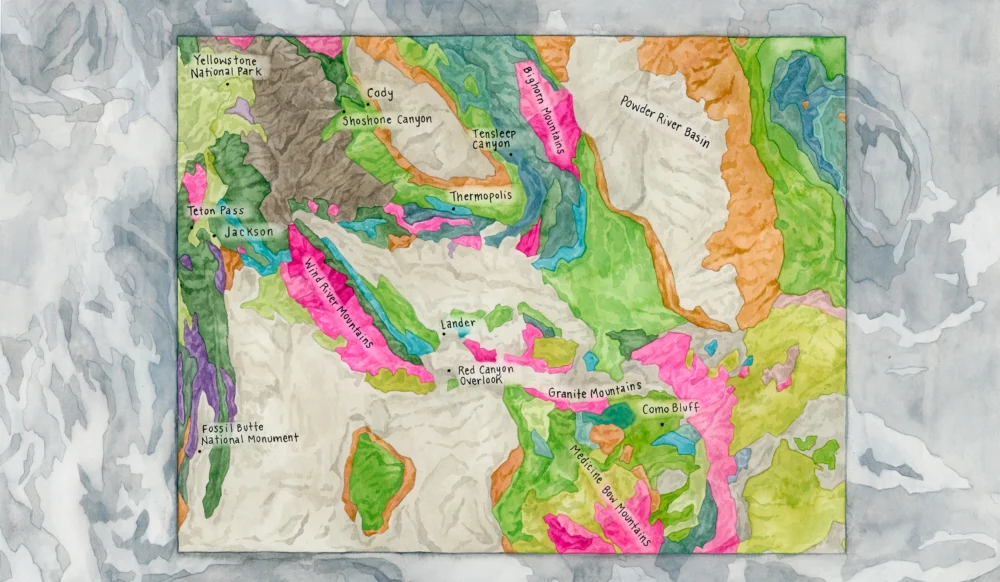

Wyoming stands as an unparalleled geological archive in the Western United States, boasting rock exposures that span nearly 80% of Earth’s existence, from 3.5 billion years ago to the present day. This remarkable continuity offers geoscientists a unique window into planetary evolution, making it an exceptional locale for deciphering deep time. Through meticulous study over decades, geologists have learned to interpret the intricate language of these ancient formations, uncovering invaluable insights into past climates, biological revolutions, and tectonic forces that shaped continents. Seeking reassurance and perspective amidst contemporary global challenges, researchers have recently engaged with ten of Wyoming’s venerable rock formations, inviting them to share the "Wyomings" they witnessed in their formative epochs, revealing a chronicle of ceaseless change and profound rebirth.

The journey into deep time begins with the Sacawee Gneiss, Wyoming’s most ancient rock, a metamorphic marvel crystallized approximately 3.45 billion years ago during the Paleoarchean Era. This venerable formation originated from magmas derived from even older granitic rocks, long since consumed by Earth’s relentless recycling processes. The Sacawee Gneiss recounts an early Earth vastly different from today: a hotter, restless planet still in its infancy, where plate tectonics, as we understand it, had not fully evolved. Magmatic activity was ubiquitous, and proper continents were absent, replaced by a scattering of nascent granite islands. Its only surviving links to ancestral rocks are microscopic zircon crystals, veritable time capsules whose radioactive decay allows scientists to precisely date the formation’s genesis. This ancient gneiss is not alone; it shares a common origin with sibling formations like the Morton and Watersmeet Gneisses found in Minnesota and Michigan, remnants of a proto-continental crust. Following its crystallization, the Sacawee Gneiss endured intense pressures and temperatures deep within the Earth, undergoing extensive kneading and folding that imparted its distinctive, spectacular stripes—a testament to its metamorphic "rite of passage." Unbeknownst to it at the time, these processes were laying the foundation for one of Earth’s earliest true continents, a stable continental shield known as the Superior Craton. This ancient landmass, of which the Sacawee Gneiss formed a crucial part, eventually broke apart around 2 billion years ago under a new plate tectonic regime, with the Sacawee fragment diverging from its siblings as an ocean opened between them. Yet, plate motions are cyclical, and hundreds of millions of years later, these fragments began to reconverge, culminating in a colossal collision that birthed the Trans-Hudson mountain range. While most of this ancient range now lies buried beneath younger strata in the Dakotas and Saskatchewan, its eroded roots peek out in Wyoming’s Medicine Bow Mountains, reminding us of past continental sutures. Exposed at the surface today, the Sacawee Gneiss, weathered by wind, ice, and rain, slowly transforms into sediment, destined for another cycle of rebirth as sedimentary rock—a poignant reminder of the planet’s infinite geological reincarnation, a stark contrast to the finite existence of mortal beings.

Following the formation of the Superior Craton and its subsequent rifting, a shallow ocean emerged, laying down the calcium carbonate muds that would become the Nash Fork Dolomite, dating back approximately 2.1 billion years to the Paleoproterozoic Era. This formation paints a picture of a "water world" teeming with life, albeit microscopic. The planet then was an energetic realm, with closer proximity to the Moon resulting in dramatically higher tides, and a faster Earth spin shortening the day to just over 19 hours. Crucially, this era witnessed the "Great Oxidation Event," a monumental inflection point in Earth’s history where photosynthesizing cyanobacteria fundamentally transformed the atmosphere from a volcanic cocktail of carbon dioxide and water vapor to an oxygen-rich environment. In this burgeoning oxygenated world, microorganisms thrived, evolving novel metabolic strategies and forming vast, lumpy mats of diverse microbial species known as stromatolites. These intricate, symbiotic communities, often described as "cabbage-like" in their layered structure, represent remarkable examples of durable, deeply recycled ecosystems—a valuable lesson in biodiversity and resilience. Geologists revere the spectacular stromatolite outcrops of the Nash Fork Dolomite, designating them "no-hammer zones" to protect their delicate structures. This period predates the emergence of animals by over 1.5 billion years, challenging the human-centric view of biosphere significance. Single-celled organisms, having ushered in the oxygen age, meticulously buffered atmospheric and oceanic chemistry for two billion years, maintaining planetary stability. It was only with the advent of animals, with their complex food webs and insatiable appetites, that the carbon cycle became prone to destabilization, rendering the biosphere vulnerable to mass extinctions—a prescient warning from deep time.

The ancient ocean that bore the Nash Fork Dolomite eventually receded, giving way to the tectonic collision that formed the Trans-Hudson mountains. A prolonged period of erosion then dominated, carving deeply into the bedrock and creating an irregular surface known globally as the Great Unconformity. In Wyoming, this geological hiatus represents a colossal gap of over a billion years in the rock record, spanning from approximately 1.7 billion to 500 million years ago, encompassing the Mesoproterozoic Era and early Cambrian Period. Often perceived as a mere absence of rock, the Great Unconformity is, in fact, a testament to immense geological forces and unimaginable stretches of time. It speaks of a time when sea levels were exceptionally low, preventing the deposition of new sediments and allowing erosion to relentlessly dismantle vast mountain ranges, erasing entire landscapes from the geological ledger. This "ghost world" of missing time is famously observed in places like the Grand Canyon, where it signifies profound changes in Earth’s crustal dynamics and atmospheric composition, including the period leading up to the "Snowball Earth" events.

Toward the end of this billion-year gap, Earth plunged into a series of extreme ice ages known as "Snowball Earth," where massive glaciers blanketed continents, even in tropical latitudes, locking up vast quantities of water and causing sea levels to plummet. As the planet finally warmed, oceans dramatically rose, inundating the denuded continental surfaces. The Flathead Sandstone, dating to approximately 520 million years ago during the middle Cambrian Period, meticulously records this global marine transgression across Wyoming’s deeply eroded landscape. This formation, part of a vast sheet of beach sand now hardened into stone, has counterparts across North America, such as the Tapeats Sandstone in the Grand Canyon and the Potsdam Formation in New York, all resting atop the Great Unconformity. The Cambrian Wyoming was an austere, treeless landscape, but beneath the advancing seas, a remarkable variety of older rocks were exposed. The Flathead Sandstone literally touches these ancient formations, offering geologists direct insights into the land surface of that distant past. Its creamy, almost pure quartz composition, eroded from granites and gneisses like the Sacawee, attests to the colossal volume of igneous and metamorphic rock that had to be weathered down to yield such abundant quartz—a testament to the immense work performed by the Great Unconformity. Traditionally, these quartz-rich sandstones were considered geologically inarticulate due to the lack of distinctive mineral grains tracing their origins. However, the discovery and analysis of rare "detrital zircons"—tiny, durable crystals carried by rivers from igneous and metamorphic source rocks—have revolutionized our understanding. These microscopic remnants, like discovering entire libraries within a seemingly blank page, now allow scientists to reconstruct long-vanished continental-scale drainage systems, proving that even seemingly simple rocks hold profound stories for patient interpreters.

Later in the Cambrian, rising sea levels buried the Flathead beach sands under deeper-water carbonate rocks. However, subsequent global cooling caused seas to retreat again, exposing the land. This re-emergence is eloquently recorded by the Tensleep Sandstone, a formation approximately 310 million years old, dating to the late Carboniferous Period. Unlike its aquatic predecessor, the Tensleep Sandstone tells a story of a barren, desert Wyoming, dominated by colossal dune fields. While land plants had evolved by this time, they were absent from this arid realm. The relentless, abrasive wind, a primary sculptor of the landscape, left its indelible mark, pitting and scarring the individual quartz grains to the point of opacity. Eventually, a new sea, the Phosphoria Sea, advanced from the west, burying the Tensleep dunes and providing a period of "blissful sleep" for hundreds of millions of years. This marine cover was both a salvation and a precursor to its eventual fate. The exceptional biological productivity of the Phosphoria Sea, with its rich organic matter, decomposed over eons into petroleum that migrated into the Tensleep’s permeable sands. Today, the Tensleep Sandstone is a significant reservoir rock, targeted by countless oil and gas wells, its ancient desert memories now fueling modern economies, a complex irony of deep time’s resources.

Wyoming remained on the western edge of the continent during this period, with the encroaching Phosphoria Sea forming a deep basin across parts of present-day Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Montana, and western Wyoming. Upwelling coastal currents delivered a continuous supply of nutrients into these shallow waters, fostering an extraordinarily rich marine ecosystem. The Phosphoria Formation, dating to approximately 290 million years ago in the early Permian Period, serves as a testament to this "biological bacchanal." Its warm, sunlit waters were a tropical marine paradise, depositing organic-rich muds that became its shales and limestones. The seafloor was carpeted with an astonishing array of brachiopods, sea snails, and sponges, while phytoplankton bloomed exuberantly at the surface, forming the base of a thriving food web. The Phosphoria Formation has preserved abundant evidence of this vibrant life, including countless fish scales and fossils of bizarre creatures like Helicoprion, a shark-like fish with a fearsome, spiral-shaped tooth whorl. However, this ecological exuberance was tragically short-lived. The world was on the brink of the Permian-Triassic extinction event, the most severe mass extinction in Earth’s history. Enormous eruptions of lava in what is now Siberia, forming the Siberian Traps, released vast quantities of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, triggering a cascade of environmental calamities: abrupt global warming, ozone depletion, widespread ocean acidification, and anoxia. This cataclysm led to the demise of at least 80% of known marine species, including many within the Phosphoria Formation’s once-thriving ecosystem. The Phosphoria Formation thus stands as a vivid memory of a bountiful world before its collapse, a world whose fossilized remains, ironically, now fuel an Anthropocene economy that risks reenacting a similar catastrophe.

The Permian extinction represented a near-death experience for Earth’s biosphere, yet life, in its enduring resilience, found a way to recover. In Wyoming, the intensely red Chugwater Group, dating to approximately 240 million years ago during the Triassic Period, vividly records the post-apocalyptic landscape that followed. This formation paints a picture of a hot, arid Wyoming, where vegetation was sparse and braided rivers snaked across a parched terrain, depositing sand and silt. Occasionally, water pooled in brackish basins, leaving behind white lenses of gypsum that permeated the river sediments. The Chugwater Group’s brilliant red-orange hue, visible even from space, comes from trace amounts of oxidized iron—essentially rust—signifying a still-recovering atmosphere with low but sufficient oxygen levels for iron oxidation. Paleontologists theorize that low oxygen levels persisted for millions of years after the Permian extinction, with marine photosynthesizers struggling to re-aerate the oceans. This challenging environment may have given an evolutionary advantage to groups with more efficient respiratory systems, such as the early dinosaurs. Indeed, the Chugwater Group holds some of the oldest known dinosaur fossils in North America, including silesaurid femur and humerus fragments, which have overturned previous notions that dinosaurs were confined to the Southern Hemisphere until the Jurassic Period. These bones offer a rare glimpse into the early diversification of dinosaurs in a world slowly recovering from the greatest ecological disaster it had ever faced.

Millions of years later, the Morrison Formation, approximately 150 million years old from the Jurassic Period, takes center stage, renowned globally for its unparalleled wealth of dinosaur fossils. This formation conjures images of a "Jurassic Park" populated by towering herbivores like stegosaurs, camarasaurs, apatosaurs, and diplodocus, alongside formidable carnivores such as allosaurs. The Wyoming of the Morrison Formation was a warm, semi-arid environment, often compared to a Mediterranean climate, though the Mediterranean Sea itself was yet to exist. Flowering plants had not yet evolved, but gymnosperms like ginkgo and cycads provided abundant forage for the massive plant-eaters. Like the Chugwater Group, the Morrison Formation comprises fine-grained river and lake deposits that attracted a diverse array of thirsty creatures. The dramatic demise of the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous Period, 66 million years ago, continues to captivate human imagination, often serving as a canvas for projecting contemporary anxieties. While the asteroid impact theory, gaining traction during the Cold War’s nuclear fears, is now largely accepted, an emerging consensus acknowledges that other factors, including massive greenhouse gas emissions from volcanic activity in India (the Deccan Traps), also contributed to the profound disruption of late Cretaceous ecosystems, illustrating the complex interplay of forces that can trigger planetary-scale change.

The geological periods immediately preceding and following the dinosaur extinction are exceptionally well-preserved in Wyoming’s rocks and landscapes. Around this time, over a span of about 30 million years, a peculiar tectonic event known as the Laramide Orogeny uplifted the iconic mountain ranges we recognize as "The Rockies," including the Bighorn, Wind River, Beartooth, Uinta, Granite, Laramie, and Front ranges. Unlike typical mountain-building events, where tectonic activity is concentrated near plate boundaries, the Laramide ranges rose approximately 800 miles inland from the Pacific coast. This anomalous uplift is attributed to the "flat-slab subduction" of the Farallon oceanic plate, which, instead of sinking steeply into the mantle, scraped horizontally beneath the North American plate until it encountered the deep, resilient crustal roots of the ancient craton forged by the Sacawee Gneiss, causing the overlying continental crust to buckle and rise. Concurrently, Earth experienced fluctuating sea levels, the catastrophic asteroid impact that ended the age of dinosaurs, and a period of dramatic global warming known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), marked by a sudden surge in atmospheric carbon dioxide. The Green River Formation, dating to approximately 50 million years ago during the Eocene Epoch, stands as a critical record of this "hothouse world" and its aftermath, often regarded by Earth scientists as a "distant mirror" reflecting our own Anthropocene era. This formation, famous for its exquisite fossils of leaves, insects, fish, and amphibians, preserves exceptional anatomical details, sometimes even soft tissues, which are prized by collectors worldwide. It also contains freshwater stromatolites, echoing the microbial empires of the Nash Fork Dolomite. The Green River Formation accumulated as muddy sediment and organic matter at the bottom of a chain of ancient lakes, meticulously documenting the plants and animals that thrived in and around these subtropical waters. Eocene Wyoming, though at a similar latitude to today, was a hot and steamy landscape, home to palm trees and crocodilians where pine forests and grizzly bears now roam. This stark climatic difference underscores the profound power of greenhouse gases to regulate global temperatures. While the exact trigger for the immense release of hydrocarbons that caused the PETM remains debated—possibly magmas igniting coal beds in the opening North Atlantic, or massive methane belches from the seafloor—the Green River Formation provides quantitative evidence of its atmospheric impact. Its beds contain a rare sodium bicarbonate mineral that only forms from evaporating waters when carbon dioxide levels exceed approximately 700 parts per million. This figure is significantly higher than our current 425 ppm, and alarming given that human evolution occurred in a world where CO2 concentrations rarely surpassed 350 ppm. The irony is palpable: the very coal seams and oil shale within the Green River Formation, testaments to past biological productivity and climate events, are now exploited by humans, inadvertently propelling us towards similar hothouse conditions. Yet, even as mountains rose during the Laramide Orogeny, erosion relentlessly worked to dismantle them, accumulating thick piles of sediment in intermontane basins, including those of the Green River lakes. This ceaseless cycle of uplift and erosion ultimately brought these ancient rock formations to the surface, making them accessible to modern observers.

Nearly 50 million years after the Eocene hothouse, northwestern Wyoming experienced a series of explosive volcanic eruptions as the North American plate drifted over a stationary "hot spot"—a rising plume of semi-molten rock within Earth’s mantle. This geological phenomenon ultimately created what is now Yellowstone National Park. The Huckleberry Ridge Tuff, approximately 2.1 million years old from the Pleistocene Epoch, formed during the first and most colossal of these events. This formation, often dubbed the "yellow stone of Yellowstone," is the product of an infamous "supervolcano," a term that evokes both fascination and dread. The eruption that created the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff sent an ash column 30 miles into the atmosphere, emptying its vast magma chamber and leaving behind the immense Yellowstone caldera. The total erupted volume was nearly 600 cubic miles, and two more massive eruptions followed over the next million and a half years. While a recurrence, though statistically unlikely in any given human lifetime, remains a possibility with devastating potential for global climate and mid-continental human activity, the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff offers a different, more immediate warning. Formed during the last ice age, it has witnessed numerous climate oscillations, yet its silent testimony expresses profound alarm at the unprecedented rapidity of climate changes observed in the last century.

These ancient rocks, from the fiery foundations of the Sacawee Gneiss to the ash-laden landscape of the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff, collectively offer a profound, enveloping narrative of Earth’s ceaseless transformations. They chronicle continents forming and breaking apart, oceans waxing and waning, ecosystems rising and falling, and an unending dance of cataclysm and rebirth. This deep time perspective reveals that landscapes are not timeless but "timeful," pulsating with billions of years of dynamic history. In this grand geological theater, human existence appears as but a fleeting act. The collective wisdom of these ancient witnesses, though silently imparted, serves as a sobering reflection for humanity, trapped in self-made systems of discord and disillusionment. While the rocks do not offer explicit advice, their enduring presence and the cyclical nature of their stories—of profound change, recovery, and the delicate balance of planetary systems—underscore the imperative for patient observation, humility, and a deep understanding of our planet’s past to navigate its uncertain future. In understanding the geological past, we are not merely doomed to repeat its errors, but rather blessed with the profound knowledge to learn from its cycles, recognizing that even in cataclysm, the Earth continuously remakes itself, offering endless possibilities for transformation and renewal.