Thirty years after witnessing the volatile events at Ruby Ridge, award-winning novelist Jess Walter returns to the profound impact of that 1992 Idaho standoff with his latest work, "So Far Gone," a novel that delves into contemporary American disillusionment and the lingering shadows of conspiracy theories. Walter, then a staff writer for The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, was drawn to the remote mountaintop cabin where an 11-day siege unfolded, resulting in the deaths of Randy Weaver’s wife and son, and a U.S. Marshal. The incident, sparked by Weaver’s failure to appear in court on charges related to a sawed-off shotgun and fueled by his anti-government sentiments and white supremacist affiliations, became a watershed moment, galvanizing the anti-government militia movement and leaving an indelible mark on the nation’s political landscape. Walter’s initial on-the-ground reporting culminated in his sole nonfiction work, "Every Knee Shall Bow," later retitled "Ruby Ridge," which chronicled the tragic events. Now, three decades into a successful career as a novelist, Walter revisits these themes, exploring a nation grappling with fractured ideas of freedom, eroding trust in institutions, and a deepening societal divide.

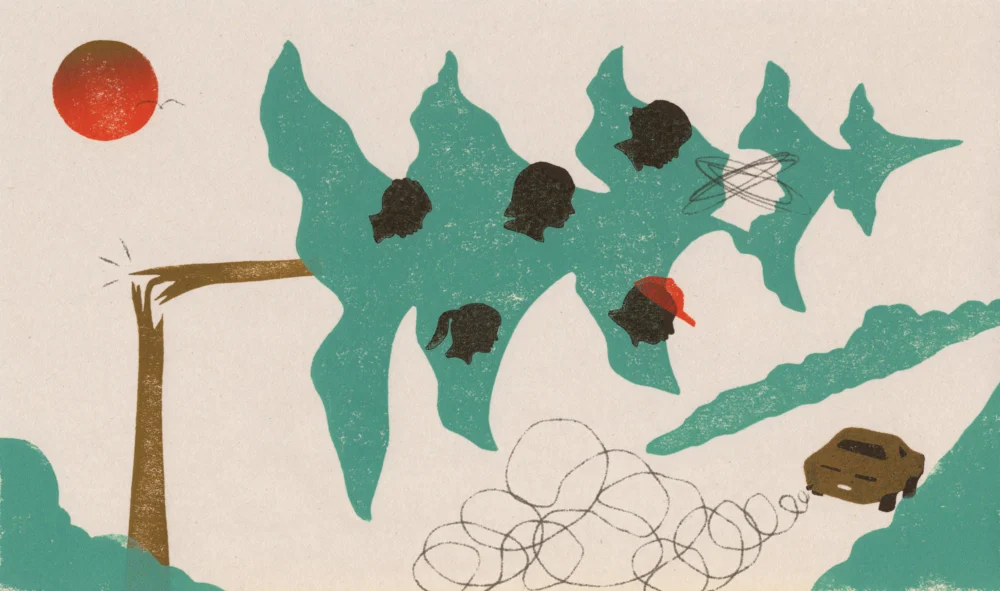

"So Far Gone" centers on Rhys Kinnick, a middle-aged, divorced man adrift in a sea of personal and political discontent. His disillusionment is amplified by his son-in-law, Shane, who has become deeply entrenched in a labyrinth of conspiracy theories, leaving Kinnick baffled by his daughter’s continued association. The narrative unfolds against a backdrop of personal setbacks—including a layoff from his newspaper and the election of Donald Trump—which collectively push Kinnick to seek solace and escape by retreating to an off-the-grid cabin. His self-imposed exile is interrupted by the unexpected arrival of his grandchildren, whom he hasn’t seen in years, with news of their mother’s disappearance and Shane’s departure in search of her.

While "So Far Gone" is not a direct fictionalization of the Ruby Ridge saga or the Weaver family’s story, it resonates with the spirit of those who might have aligned with them, exploring the fertile ground from which such sentiments grow. Set in and around Walter’s hometown of Spokane, the novel serves as a profound examination of disillusionment and its far-reaching consequences. "I think that disillusionment is one of the most human things that happens to us," Walter explained, "So, for Rhys to suddenly find himself the disillusioned one and feeling pushed out of society struck me as a great starting point for a novel." This sense of alienation is a recurring motif, not only for Kinnick but also for his daughter, who struggles to comprehend Shane’s immersion in the world of well-armed religious separatists in Idaho.

Walter himself has spoken about his growing anxiety over the political climate, a feeling starkly illuminated by his phone’s screen time report. "It informed me that I had been spending five and a half hours a day on my phone, doomscrolling," he told High Country News. "I realized I couldn’t go on like this, imagining the demise of the country. I imagined myself going into a metaphoric woods to write the novel, turning my back on all of it." This personal experience of digital overload and existential dread mirrors the characters’ struggles, providing an authentic undercurrent to the narrative.

Despite the heavy themes of conspiracy theories and the blurred lines between militia groups and religious congregations, "So Far Gone" is infused with Walter’s signature humor, brought to life by a quirky ensemble of characters. One memorable scene depicts Kinnick’s exasperation as Shane espouses elaborate theories about a clandestine conspiracy within the NFL, positing that global elites are manipulating the sport to control the populace. Later, a seemingly absurd gunfight erupts over a set of brand-new truck tires, a testament to the unexpected and often irrational turns human conflict can take. Walter views this comedic lens as a crucial element, asserting that it makes the story "in some ways more real, and that makes it more horrible." He elaborated, "People do get shot over things like tires. I believe so fully in the folly and fallibility of human beings; in many ways, it’s the only constant. So I don’t write humor as an effect; I write it as a philosophical underpinning of the world as I see it." This perspective underscores his belief that humor, rather than being a mere comedic device, serves as a profound observation of human nature.

In the thirty years since he first encountered the anti-government sentiments that coalesced at Ruby Ridge, Walter has observed a significant shift: once fringe conspiracy theories have infiltrated the mainstream. "Now, we live in such a conspiracy-rich world," he remarked, adding, "I don’t think Ruby Ridge was the cause of this so much as a harbinger of what was to come." This observation speaks to a broader cultural phenomenon, where distrust in established institutions and a propensity for alternative narratives have become increasingly prevalent, shaping political discourse and social interactions globally.

"So Far Gone" masterfully captures this contemporary moment, a period defined by Americans grappling with a perceived loss of purpose amidst a pervasive and deepening political polarization. The novel offers a nuanced exploration of how individual disillusionment can intersect with broader societal anxieties, creating a complex tapestry of human experience.

Walter is also revisiting his foundational work, "Ruby Ridge," preparing its first update since 2008. This revised edition will include a new afterword acknowledging the passing of Randy Weaver in 2022 and Gerry Spence, Weaver’s renowned and often fiery attorney, who died in August. The update will further explore the trajectory of anti-government sentiment in the American West, tracing its evolution and influence since the Ruby Ridge incident. "Part of the update is looking at the way in which conspiracy theories have not only been absorbed into the mainstream, but have really become a winning political formula," Walter stated, highlighting the enduring relevance of his early journalistic endeavors.

Despite the gravity of the subjects that have occupied his life and writing for decades, Walter maintains a profound sense of optimism. "My son calls me a toxic optimist because I am so optimistic in general," he shared. "I’m optimistic about human beings and their capacity for change and decency." This enduring belief in humanity’s inherent goodness and potential for growth serves as a vital counterpoint to the darker themes explored in his work, suggesting that even in the face of profound societal challenges, the possibility for redemption and positive transformation remains. His continued engagement with the legacy of Ruby Ridge, through both his fiction and updated nonfiction, underscores his commitment to understanding and illuminating the complexities of the American psyche in an era of unprecedented change.