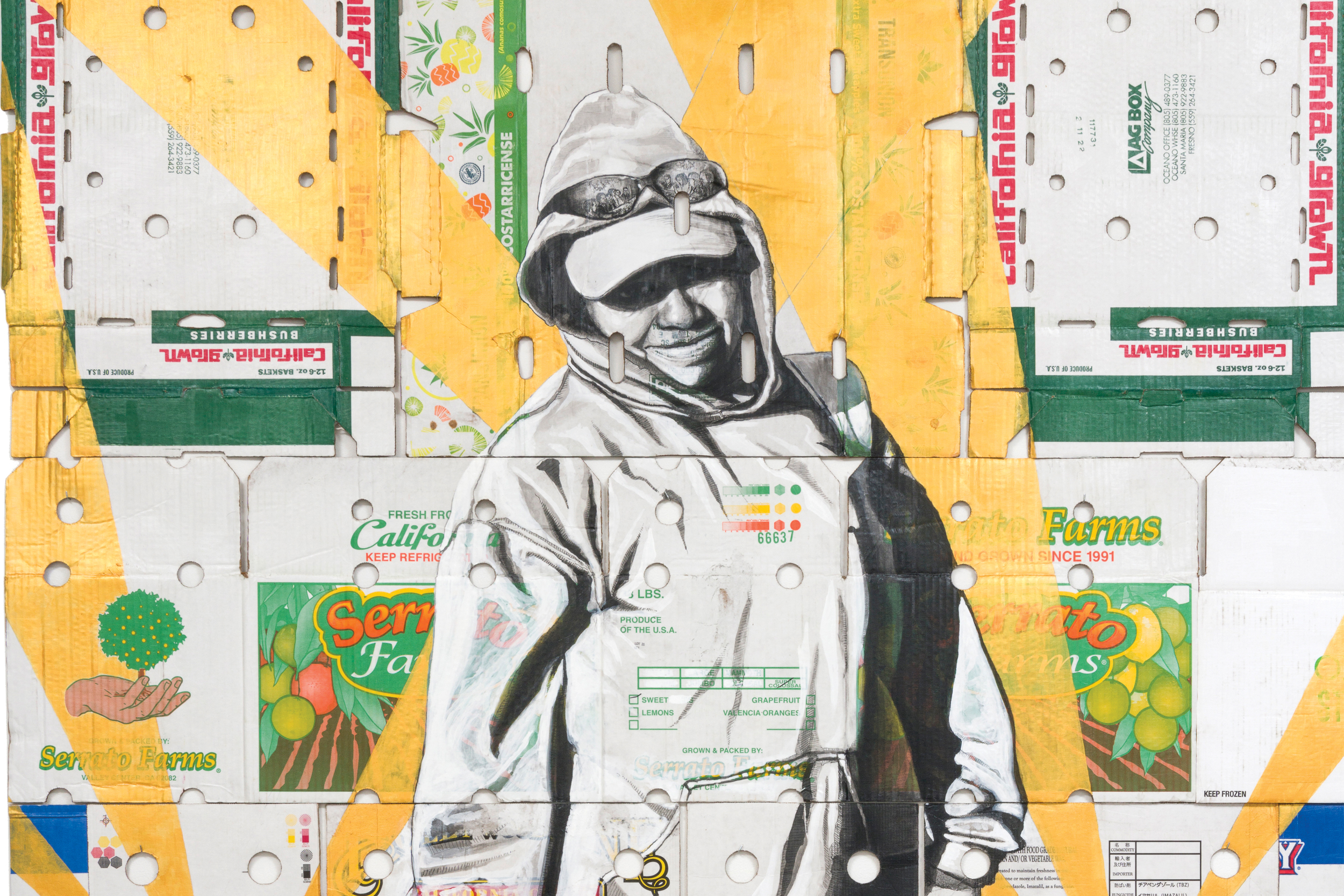

Born in Oaxaca, Mexico, in 1977, Narsiso Martinez arrived in the United States at the age of twenty, embarking on a journey that would lead him to earn a master of fine arts degree in drawing and painting from California State University, Long Beach. His distinctive artistic creations have since been showcased in exhibitions both locally and internationally, finding homes in the esteemed collections of institutions such as the Hammer Museum, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, the University of Arizona Museum of Art, the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon, and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Currently residing and working in Long Beach, California, Martinez shared insights into his artistic practice and motivations.

Martinez’s unique artistic process began in earnest around late 2016 or early 2017, a pivotal moment that stemmed from his earlier experiments with oil paintings on cardboard. During a three-year period between undergraduate and graduate studies, he spent time working in the agricultural fields of Washington state, living with his sister. It was then that he began utilizing discarded produce boxes, often sourced from Costco through his sister, as a canvas for his drawings and sketches. Initially, he focused on the blank interior surfaces of these boxes, the "good" part, without yet considering the printed labels as an artistic element.

The conceptual shift occurred when Martinez returned to graduate school in 2015, facing limitations with oil painting on canvas. While collecting a banana box from a Costco in Los Angeles, he was inspired to draw a "banana man" directly onto the box itself. This spontaneous creation, born from a personal artistic impulse rather than a specific assignment, eventually led to a profound realization during a class critique. With the guidance of his peers and faculty committee, he understood that his work was an exploration of the working class, and more specifically, a commentary on agribusiness and the lives of farmworkers, directly informed by the materials he was using. This convergence of personal experience and artistic medium marked the genesis of his distinctive body of work.

Martinez’s experiences in the agricultural fields profoundly influenced the evolution of his art. He explained, "I’ve always been a little shy. That’s why I do art. And when I discovered that through art, we can say things, and people can see things, I thought that I could use art to bring awareness about people in the fields, about my community and my own experiences." He began working in the fields in 2009, shortly after transferring to Cal State Long Beach. Facing financial challenges with tuition, his family, who were already engaged in farm labor, offered him support with food and lodging if he joined them. This decision led him to dedicate significant portions of his academic career to farm work, saving his paychecks and working every season during his undergraduate studies, followed by a full year for three years, and then summers throughout his graduate program. This commitment amounted to approximately nine years spent in the fields, often traveling to Washington state immediately after school ended to maximize his time there before returning just as classes were set to resume.

His labor in the fields encompassed a variety of crops, starting with asparagus, a particularly demanding task due to the constant need to bend over in the absence of shade. He also harvested cherries, multiple varieties of apples such as Gala, Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, and Fuji, as well as peaches and blueberries. These firsthand experiences provided him with an intimate understanding of the physical toll and challenges faced by agricultural laborers.

Martinez’s art aims to bridge the gap between consumers and the essential workforce that sustains them. "For me, it’s important to tell the public who is behind our food production," he stated. "I want to highlight the farmworkers. I want to raise awareness of their presence, of their contributions, of their humanity. I feel like farmworkers have been neglected throughout history, here in the United States and abroad. Dignify farmworkers: That’s the goal." This mission resonates deeply within his practice, transforming discarded materials into powerful portraits of dignity and recognition.

The farmworkers themselves have often been deeply moved by Martinez’s art. Having worked alongside many of them, he developed personal connections, with individuals often requesting to be drawn. "When I was in the fields, I got to meet a lot of farmworkers. Eventually they would know me, because I would carry my sketchbook around. And they would say, ‘When are you gonna draw me?’" He shared that being acknowledged through art evokes a sense of belonging and contribution, mirroring his own experience of validation upon receiving his first identification card. He has organized exhibitions specifically for farmworker communities, where the response has been overwhelmingly positive, fostering shared narratives and reinforcing their sense of importance. "I hope they can see themselves in the art, and the importance that they bring to the country. We need to be seen. We need to be taken into account," he emphasized.

Reflecting on the power dynamics within the food system, Martinez observed the stark contrast between the vital role farmworkers play and their historical marginalization. "When I came to the United States, I came with no education. And from what little I’ve learned it seems like the system was designed to keep oppressing farmworkers. Historically, the more vulnerable communities have been working the fields, picking the food that we consume." He expressed dismay that this essential group has often been denied a dignified existence, despite being the very individuals who produce the sustenance that sustains society. He views farmworkers as having been politically exploited, often serving as scapegoats, and noted the persistent lack of a dignified life for them throughout history, a reality he finds deeply saddening. Martinez advocates for public support of legislation aimed at improving the lives of farmworkers, calling for a more equitable and humane approach.

When asked about common misunderstandings surrounding farmworkers, Martinez stressed their fundamental humanity. "Farmworkers are human beings. Besides our contributions, farmworkers are human beings with goals, dreams, aspirations, struggles. We go through sadness, happiness, just like anybody else. I feel like it’s about time to recognize that, no?" This sentiment underscores his desire for empathy and a broader societal understanding of farmworkers as individuals with complex lives beyond their labor.

Martinez views his work as particularly relevant amidst contemporary political climates, including the targeting of agricultural workers. "I feel like it’s unfair what’s happening right now. I can’t believe people who are in the fields, picking the food, are being persecuted. That’s unacceptable, no?" He drew parallels to the historical struggles for labor rights, citing the United Farm Workers Movement initiated by leaders like Larry Itliong, Cesar Chavez, and Dolores Huerta, who fought for improved conditions and dignity for farmworkers. He expressed gratitude for organizations actively supporting farmworkers and advocating for their safety and rights against deportation and other forms of persecution, remarking on the disturbing imagery of military presence in agricultural areas as a consequence of political maneuvering.

The widespread recognition and inclusion of his work in major museum collections have been a profound surprise for Martinez. "When I started, I didn’t know where I was going to go with this. I didn’t know that it was going to get this far. I’m really grateful, because the art is not only (addressing) the inclusivity of farmworkers as a subject matter, but is being included in (the collections of) big museums." He finds it remarkable that art created by an immigrant, an Indigenous immigrant, can resonate with diverse audiences, including farmworkers, academics, researchers, and museum professionals.

Martinez’s journey to the United States as a young adult from a small village in Oaxaca was marked by significant culture shock, from the imposing urban landscapes to the complex social dynamics. "When I came, I had no education. I was basically blind. I didn’t understand even my own culture." He found solace and a path forward through education, particularly by learning English at an adult school. This linguistic bridge enabled him to connect with his teachers, who instilled in him the belief that he could pursue higher education, a path he gratefully followed. His education provided him with a broader perspective, enabling him to understand his place within a larger historical and social context. He recognized the intertwined histories of colonization and the imposition of systems that continue to create struggles for equity, particularly for Indigenous peoples who often find themselves excluded.

His artistic practice is deeply rooted in the rich sociopolitical and labor-focused art traditions of Mexico, particularly the muralist movement. "I would say yes," he confirmed when asked about this connection. Learning about Mexican muralists like Siqueiros while studying in the United States significantly impacted him, especially Siqueiros’s "América Tropical" mural, which resonated with his own Zapoteca heritage and the depicted struggles. The concept of muralism informs his larger works, which involve collaging diverse images to create a cohesive narrative on a grand scale, aiming to evoke strong emotional and intellectual responses in viewers.

Looking ahead, Martinez envisions his work expanding to encompass the global struggles of farmworkers. "The more I learn, I realize that farmworkers are struggling everywhere in the world." He sees a continuity of struggle, from his own experiences in Oaxaca to the contemporary globalized agricultural industry where large corporations exert influence. His future plans include visiting and potentially working in orchards and fields in other countries to document and connect the experiences of farmworkers worldwide. He is keen to explore the common threads that bind these diverse communities, seeking to understand the universal challenges faced by those who cultivate the world’s food supply.