The Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, pulsed with an almost palpable energy in January 1967 as 24-year-old Tanya Atwater arrived to commence her graduate studies. Hallways at the prestigious institution were strewn with long rolls of magnetic data, recently retrieved from forgotten corners, each squiggle a potential clue in a burgeoning scientific mystery. Weeks earlier, a pioneering Cambridge geophysicist, Fred Vine, had visited Scripps to articulate a revolutionary concept, then informally known as the Vine-Matthews Hypothesis or seafloor spreading. This burgeoning theory was set to drastically advance the long-dismissed notion of continental drift and would, in time, coalesce into the foundational paradigm of plate tectonics, fundamentally reshaping humanity’s comprehension of Earth.

Atwater, a self-described "full-on Berkeley hippie" known for her barefoot presence, beads, and flowers, was a striking figure in a scientific domain overwhelmingly dominated by men. Armed with an undergraduate degree in geophysics and a rare intuitive grasp for the larger geological narrative, she possessed a unique perspective. Her very first marine geology class diverged from the syllabus, as her professor, swept up in the unfolding intellectual storm, launched directly into this "wonderful new idea" that was already transforming oceanography and promised to rewrite the very history of continents. Textbooks, he declared, were already obsolete. Atwater had unwittingly stepped into the epicenter of a profound scientific revolution.

The concept of continents fitting together like jigsaw puzzle pieces had intrigued thinkers since the advent of accurate world maps, yet for centuries, mainstream geology remained entrenched in "fixism," the belief that landmasses had remained static since Earth’s formation. Despite this dogma, paleontologists globally unearthed identical rock layers containing similar fossils—a Permian reptilian creature found in both Brazil and southwestern Africa, or a specific fern species scattered across the Southern Hemisphere. Such discoveries posed an insurmountable biogeographical challenge: how could land-bound species and flora traverse vast oceans?

In 1915, German meteorologist Alfred Wegener proposed a solution in his seminal work, The Origin of Continents and Oceans, suggesting that continents had once been conjoined in a supercontinent he termed Pangaea and subsequently drifted apart. However, amidst the turmoil of World War I, his ideas initially garnered little attention. When the third edition of his book was translated into multiple languages, it instead became a target for widespread scientific ridicule. American geologists, in particular, "pooh-poohed" the idea, largely due to the absence of a plausible mechanism to explain such immense movement. Despite the scorn, the compelling notion of continental drift stubbornly persisted.

Atwater’s path to this scientific maelstrom was serendipitous, a "lucky chance of having the right background at the right moment in the right place." Born in California on August 27, 1942, her early artistic aspirations shifted dramatically with the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik in 1957, igniting a fascination with the potential of science. Encouraged by her engineer father and botanist mother, she explored scientific degrees, encountering the pervasive sexism of the era when Caltech rejected women and Harvard directed her to Radcliffe, where she lacked classical language prerequisites. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, however, welcomed women into its science programs, albeit with the patronizing explanation that they would "raise great children," interpreted by Atwater as primarily boys. Such dismissals, she later noted in Plate Tectonics: An Insider’s History of the Modern Theory of Earth, were regrettably common.

Her early academic journey at MIT saw her explore five different majors, finding organic chemistry "just horrible" and electrical engineering fraught with accidental electrocutions. A transformative field course in Montana, however, provided her first hands-on experience with geology. Hiking through mountains, understanding their intricate geometry, and translating it onto maps, she felt a profound connection. "Suddenly, the landscapes and the rocks, they were talking to me," she recalled. Geology, though perceived as a "grubby and obscure field" removed from her initial high-tech aspirations, captivated her. Frustrated by professors who offered no coherent explanation for volcanoes or crumpled mountains, she initially found the field baffling, with forces attributed to "the hands of a capricious god." This conceptual void led her to drop out of MIT, travel, and deliberate, yet the mountains continued their silent discourse.

The stark, exposed landscapes of California, where "the rocks are all standing up and yelling at you," ultimately drew Atwater back to her home state. She enrolled at the University of California-Berkeley during the tumultuous Free Speech Movement, a vibrant hub of counterculture and anti-Vietnam War protests. Despite geology’s declining enrollment and its association with the petroleum industry, Atwater pursued geophysics, integrating her MIT math and physics credits with an intense schedule of geology courses. It was a time of cultural upheaval, yet she immersed herself in the study of Earth’s slow, monumental forces.

After graduating with a B.A. in geophysics in 1965, Atwater headed east for a summer internship at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. At this time, oceanography and geology were largely siloed disciplines. She was drawn simply by "the romance of going to sea," unaware of the profound geological processes unfolding beneath the waves. Her perspective shifted dramatically when she attended a meeting in Ottawa, Canada, where geophysicist J. Tuzo Wilson delivered a seminal lecture on "transform faults"—a novel geological feature characterized by horizontal, rather than vertical, movement. These faults, Wilson explained, intersected mid-ocean ridges, the long chains of undersea mountains where new oceanic crust formed as magma welled up. These ridges and faults segmented Earth’s crust into vast, rigid plates, which moved slowly, creating a jagged, stair-step pattern across the ocean floor. Wilson, a recent convert from fixism to the "drifter" camp, used simple paper diagrams with instructions to "Cut here, fold here, pull here" to illustrate his hypothesis, drawing laughter and embarrassment from the audience. Yet, Atwater, intrigued, recreated the model privately in her hotel room, sensing its profound implications.

Crucially, Wilson had alluded to an unusual transform fault occurring on land: California’s San Andreas Fault. This colossal fracture, stretching 800 miles from Mendocino to the U.S.-Mexico border and extending 10 miles deep, is not a single crack but a complex network. Its horizontal movement is visibly striking on the Carrizo Plain, where dry creek beds abruptly jump hundreds of feet sideways upon reaching the fault before continuing their course. The devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which killed thousands and leveled much of the city, had spurred the first intensive study of the San Andreas. Geologist Andrew Lawson’s Earthquake Investigation Commission painstakingly mapped the fault, documenting widespread horizontal shifts of up to 21 feet, confirming the land’s northwesterly and southeasterly displacement.

For decades, the idea of continental drift remained a fringe concept. However, in 1963, Fred Vine and his colleague Drummond Matthews published a seminal paper in Nature, proposing that symmetrical magnetic anomalies on the ocean floor could be explained by the imprinting of Earth’s magnetic field on freshly cooled lava at mid-ocean ridges. As new magma surfaced and spread, it recorded alternating periods of normal and reversed magnetic polarity, creating a "zebra-pattern" of magnetic stripes parallel to the ridges. This implied two radical concepts: Earth’s magnetic field had periodically reversed, and, more significantly, the seafloor was actively spreading. Despite oceanographers having collected such magnetic data for years, its profound significance remained unrecognized until Vine and Matthews. Their theory, however, was met with skepticism, even dismissed as "unconvincing" and "heretical."

James Heirtzler, who led a magnetic profiling team at Lamont Geological Observatory in New York, initially shared this skepticism. However, in early 1966, two of his graduate students discovered a startling, perfectly symmetrical pattern in magnetic data collected the previous year by the research vessel Eltanin in Antarctic waters. Heirtzler, initially incredulous, spent a month processing the implications. Later that year, at an international scientific meeting in Santiago, Chile, he presented these findings. Atwater, then in Santiago for a geophysics job, was present. While many attendees, accustomed to dry, plankton-focused presentations, departed for lunch, Atwater remained. Heirtzler’s slide, a "wiggly line" that was undeniably "symmetrical," precisely matched the ridiculed Vine-Matthews Hypothesis. Heirtzler later wrote, "There may be no other natural phenomena where nature shows such order."

Even more powerfully, this profile could be dated. A U.S. Geological Survey team in Menlo Park had meticulously established a timeline for magnetic field reversals over the past four million years by analyzing volcanic rock samples—research previously dismissed as obscure. Heirtzler juxtaposed the Eltanin data with this reversal timeline. "It matched perfectly," Atwater recalled, "It was ironclad." Seafloor spreading was unequivocally real. This revelation struck the 24-year-old scientist like a lightning bolt; California, her home state, was at the heart of a radical new understanding of the Earth. She immediately knew she had to return.

Upon her arrival at Scripps in January, Atwater plunged into the electrifying atmosphere generated by Fred Vine’s recent visit. Students and professors frantically re-examined old magnetic profiles, now recognizing the symmetrical patterns everywhere. "They dug them all out and looked at them again: ‘Oh my God, there it is, the pattern!’" Atwater recounted. Long-time fixists transformed into drifters seemingly overnight, marking a profound paradigm shift, at least for those focused on the ocean floor.

However, land-based geologists remained largely detached, viewing the "ocean" as a separate, less relevant realm. They needed a bridge, a "translator," and Atwater, uniquely positioned with experience in both terrestrial and marine geology, was poised to fulfill this role. Her student status proved irrelevant; the plate tectonic revolution was a great equalizer, as one contemporary observed, placing "everyone in the same boat, regardless of age or experience." Yet, this equality did not extend to gender: women were typically barred from research vessels due to lingering superstitions and concerns over shared facilities. Atwater, a member of the Deep Tow research group preparing for an expedition to the Gorda Rift off Northern California, faced this discrimination. When Scripps scientists debated what to do with "the girl," her advisor, John Mudie, cut through the impropriety: "She could sue you, you know." "That’s all it took," Atwater stated, securing her place on the Gorda Rift expedition.

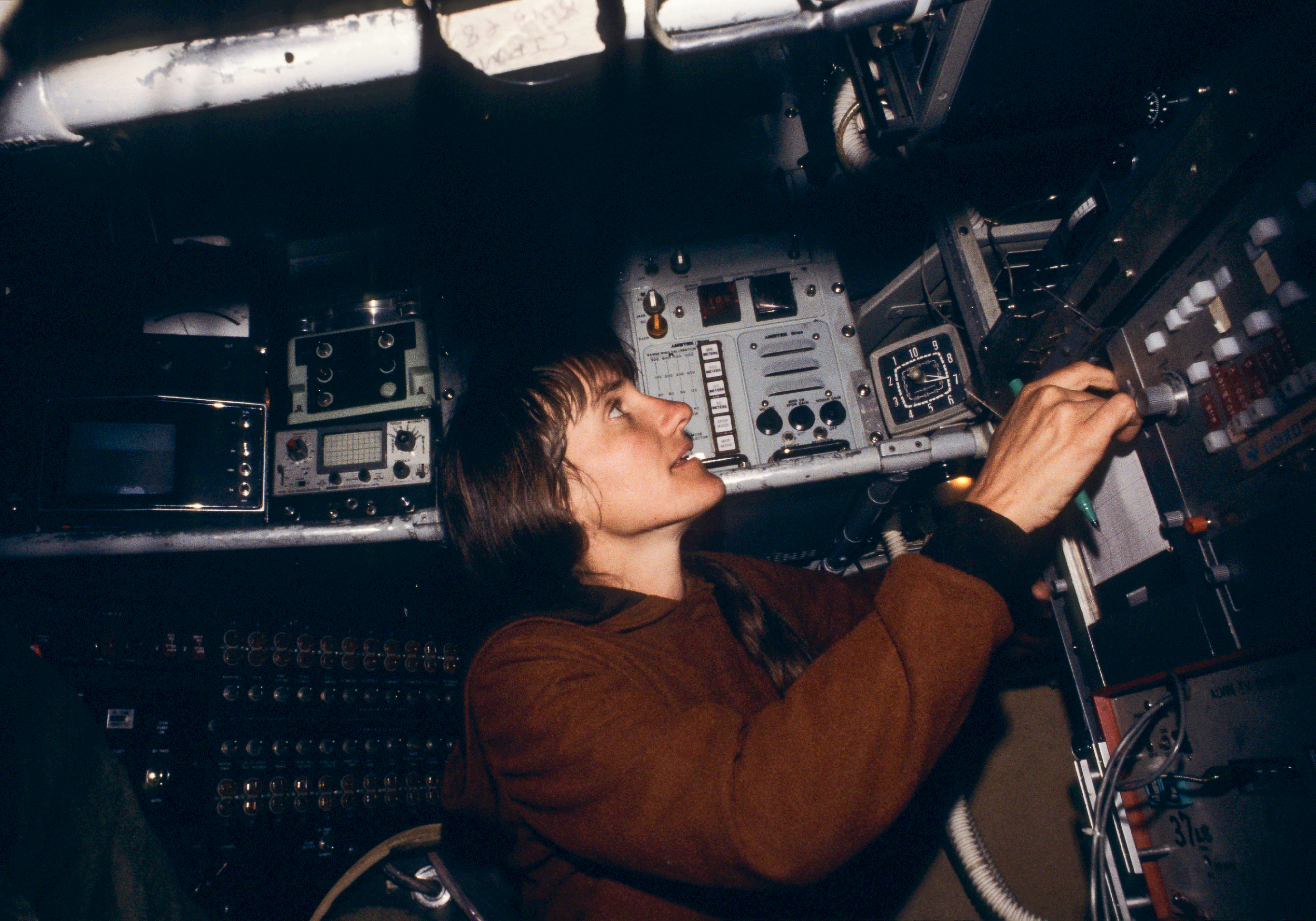

Aboard the research ship, students meticulously controlled instruments towed just above the seafloor, navigating perilous undersea topography. Observing real-time sonar images of a mid-ocean rift—its "center fallen in and fresh lava pouring over the seafloor"—crystallized Atwater’s understanding. By this time, Vine and Matthews had further refined their hypothesis, explaining that thousands of miles from its origin, the seafloor was ultimately consumed by oceanic trenches, "chewed up and recycled in the ever-moving mantle," a process they unromantically termed a "conveyor belt." Atwater was witnessing the churning, eternally young nature of the seafloor firsthand.

The next pivotal moment in Atwater’s career emerged from a sketch on a napkin during an autumn 1967 conversation with visiting scientist Dan McKenzie. At a dance hall near Scripps, McKenzie diagrammed the San Andreas Fault, revealing a critical secret: a third plate bordered the Pacific and North American plates just off Cape Mendocino, one of California’s most seismically active regions. McKenzie, who had not yet published his work on "triple junctions," illuminated a crucial geometric key for Atwater. She realized that these triple junctions, seafloor-spreading centers, and transform faults were fundamental to the entire geometry of the ocean. Crucially, if she could apply these oceanic concepts to the San Andreas, a continental plate boundary, she could integrate the entire theory of plate tectonics onto dry land.

One significant hurdle remained: the magnetic reversal timescale, though revolutionary, only extended back a paltry four million years, barely into the Pliocene epoch. The San Andreas, however, was widely believed to be much older, perhaps even 100 million years. Atwater recognized that if she had reliable, longer-range dates, she could use the offshore zebra-stripe patterns to determine the fault’s true age and movement rate. This critical work was underway at Lamont Geological Observatory. In 1968, James Heirtzler published a "wildly speculative" 85-million-year timeline for magnetic reversals, stretching back to the Late Cretaceous, the age of dinosaurs. While "their best guess was very good," Atwater noted, its unproven nature made her hesitant to publish a paper riddled with uncertainties.

That spring, Atwater presented her Gorda Rift findings at an American Geophysical Union meeting in Washington, D.C., a successful lecture preceding her first publication in the prestigious journal Science. Flush with this early victory, she joined a student group touring Lamont, only to confront stark sexism. "I was invisible," she wrote, recounting how hosts introduced "all the young men and skipped me, every time."

However, that autumn, the research vessel Glomar Challenger embarked on a deep-sea drilling expedition across the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, collecting sediment cores. The fossils embedded within these samples provided a definitive means to date the oldest layers. To the astonishment of many, Glomar Challenger‘s data precisely confirmed Heirtzler’s "speculative" 85-million-year magnetic reversal timeline. This was the missing piece.

Within months, Atwater abandoned her official Deep Tow work to immerse herself in the study of the San Andreas. This period marked the most intense of her career, filled with sleepless nights and calls to her mentor at 2 AM. Her focus centered on an anomalous, one-sided zebra-stripe pattern off the Pacific coastline—the eastern half of the pattern was conspicuously absent, baffling many scientists. McKenzie’s triple junction concept offered a crucial insight: the third plate he had revealed to Atwater was the remnant of an ancient Farallon plate, once situated between the Pacific and North American plates. Over millions of years, the Farallon plate had been pulled beneath, or subducted under, the North American plate, carrying its missing magnetic signature with it.

Atwater then masterfully pieced together the subsequent geological narrative. Only after the Farallon plate largely vanished, leaving behind fragmented pieces, could the Pacific plate directly abut the North American plate, giving rise to the San Andreas Fault. Utilizing the now-validated Glomar Challenger data, she could meticulously trace this speculative history back 85 million years. Her breakthrough revealed that the San Andreas was far younger than previously thought, no older than 23 million years. With this crucial piece of information, Atwater conclusively demonstrated how the unseen, dynamic movements of oceanic plates had profoundly shaped California’s geography and geology, compelling terrestrial geologists to acknowledge the relevance of plate tectonics to their work.

In December 1968, the Geological Society of America convened a landmark five-day meeting at the Asilomar Conference Grounds in Pacific Grove, California, dedicated to "the new global tectonics." Tanya Atwater, adorned in her customary flowers and beads, stood as the sole woman invited to speak, possibly the only woman in the packed room. As she presented her groundbreaking findings, detailing her reconstruction of California’s geological evolution, she ran over her allotted time. The moderator attempted to interject, but a voice from the captivated audience urged, "Let her go on! This is great stuff." Atwater continued. When a skeptic challenged the remarkably young age she proposed for the San Andreas, questioning its contradiction of established geological opinions, another scientist, Ken Hsu, who had been aboard the Glomar Challenger, passionately defended her work: "It’s true! Believe it!" The audience was stunned.

Atwater had become the first scientist to utilize the newly deciphered secrets of the seafloor to explain a major geological feature on land. She demonstrated that magnetic data could effectively reconstruct the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates across millions of years. This "dance of the continents," as J. Tuzo Wilson termed it, explained not only the San Andreas Fault but also California’s distinctive earthquake patterns, the formation of the Coast Ranges, the volcanism of the Cascades, and the opening of the Gulf of California. She meticulously tracked this story from the start of the Cenozoic Era, 66 million years ago, linking the extinction of dinosaurs to the rise of mammals and the epic rending and suturing of continents and seas. One listener later reflected, "I felt I had just been witness to the end of an era, and the beginning of a totally new approach to understanding the dynamics of the Earth."

Following Asilomar, speaking invitations poured in. Atwater’s unique ability to translate complex oceanographic discoveries into comprehensible earth science packed lecture halls. "I gave a bazillion talks everywhere," she recalled, with audiences drawn "partly to see the girl geophysicist, but also to hear what the revolution could mean for them." A year after Asilomar, her findings were formally published in The Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, becoming essential reading for geology students globally. Despite her burgeoning fame, Atwater, still a student herself, felt she "deserved it."

She earned her Ph.D. in oceanography from Scripps in 1972. Two years later, her son, Alyosha, was born, a milestone she emphasizes for younger women to know that balancing a demanding career with family life is achievable. After seven years teaching at MIT, she returned to the West, spending the remainder of her illustrious career at the University of California-Santa Barbara, overlooking the Santa Ynez Mountains. Her pioneering fieldwork included 12 descents into the ocean floor aboard the 6-foot submersible Alvin, often challenging prevailing gender norms, such as convincing colleagues that sharing cramped sleeping quarters with men was acceptable. While acknowledging that "there’s still some of the same silliness" for women in science, she humorously notes that she once "owned the ladies’ room" at American Geophysical Union meetings but now has to "stand in line."

Atwater credits her parents for instilling the conviction that she could pursue any ambition. While she once worried about her frequent changes in major, she now sees each step as leading her toward her destiny. Now a professor emerita, she continues to inspire, joining university field trips to share her passion for geology amidst California’s rugged mountains and jagged coastline. Since the mid-1990s, she has leveraged her artistic talents to create digital animations illustrating plate movements, "showing all the things that I can see in my head," from the global breakup of Pangaea to the complex formation of California’s Transverse Ranges and Channel Islands, which famously rotated 110 degrees clockwise 18 million years ago, a movement continuing to this day.

Science, much like the Earth itself, remains a dynamic process. Atwater, with a hint of surprise, admits she still anticipates a new idea that might overturn plate tectonics. "But it hasn’t," she observes. "We make more measurements and it’s more precise. We never know for sure; we can never prove anything is true. But this is about as sure as you can get." She concludes with a sense of quiet satisfaction, "It’s a relief, since I spent my whole life on it." Her enduring legacy underscores the power of intellectual curiosity, perseverance, and the courage to challenge established dogma in advancing our understanding of the planet.