The life of a petroleum geologist shaped my early understanding of the Earth, a profession that often meant long periods of absence for my father, who spent much of my childhood immersed in the demanding world of oil rigs across the Powder River Basin and other remote corners of Wyoming. These were the days of isolated "man camps," long before instantaneous communication, where a phone call required a multi-day wait until he could reach the nearest town for a shower and a payphone. Those calls were moments of breathless anticipation, where my sister and I would eagerly share every trivial triumph: "I got an A on my math test! I have a new crush on Matt! Sparky can now shake paws!" His returns were always a cherished event, marked by our joyous leaps on the sidewalk, a welcoming committee for the man who smelled distinctly of gasoline and grease. I would meticulously help him carry his specialized tools – the UV box, the offset logs – into the house, alongside the treasures he’d gather on his prairie walks: peculiar rocks, ancient arrowheads, shed antlers, and once, a delicate piece of china, optimistically adorned with a sprig of roses, unearthed from a long-abandoned homestead.

A dramatic shift in the global energy landscape, however, brought my father home more permanently during my junior high years. The bust in the oil industry meant my mother took on longer hours, while my dad became the steady presence in our mornings. As my sister and I meticulously curled our hair amidst a cloud of hairspray, he would prepare our toast and drive us to school. Each journey was an informal education. At a specific traffic light, dubbed "New Word Light," he introduced a new vocabulary word daily, challenging us to use it three times before the day ended. Words like troglodyte, ennui, and pernicious became part of our lexicon, indelible markers of those commutes. Another corner, "Question Corner," served as a forum for profound inquiries. My sister, with youthful existentialism, questioned divine justice in the face of hunger, while I sought to comprehend the complexities of the Vietnam War and the raw experience of parental loss. It was during one of these drives that he unveiled a concept that, at the time, felt utterly incomprehensible: if Earth’s entire history were condensed into a mere 24-hour day, he explained, human existence would occupy only the last few fleeting seconds before midnight. The last few seconds before midnight. A stark realization that, despite our brief appearance on this vast timeline, humanity has undeniably etched its mark upon the planet.

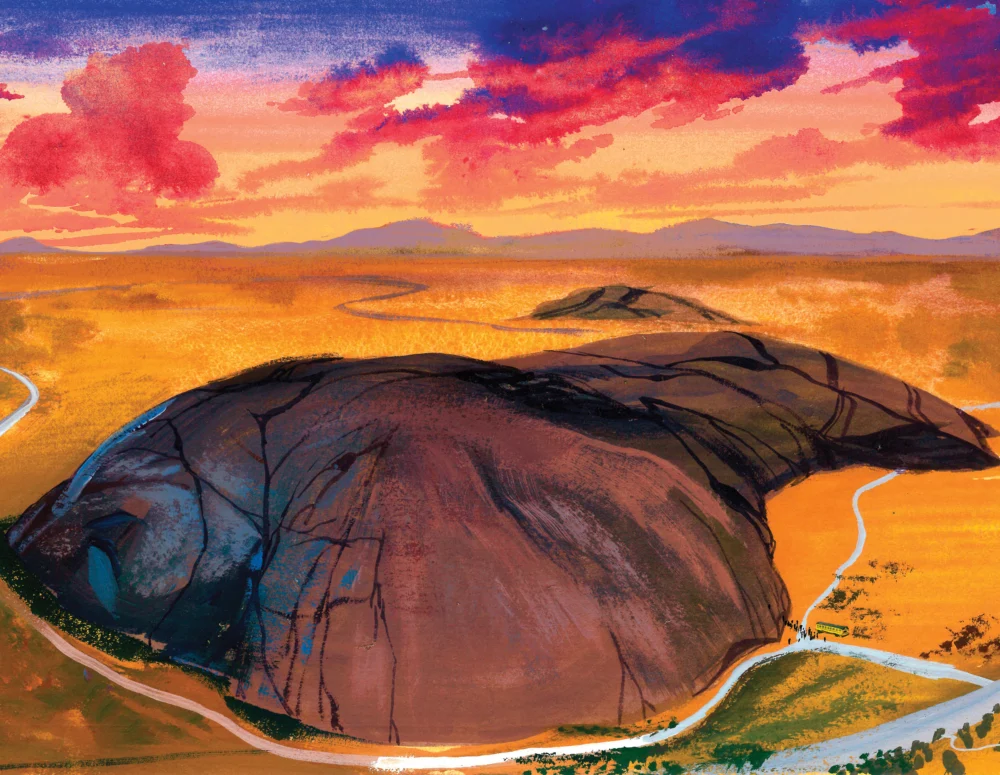

This profound sense of deep time, the immense span of geological history against the ephemeral human experience, was further reinforced by regular school field trips to Independence Rock. Affectionately known as the "turtle of the prairie," this colossal granite monolith, resembling a giant turtle shell nestled amidst the sagebrush, was a mere hour’s drive from Casper, making it an ideal destination for elementary school excursions. The bus would sway and shake in the relentless Wyoming wind as we approached, and our picnic lunches were a highlight, savored in its shadow. It was there, too, amidst the vastness, that I learned the pragmatic art of relieving oneself in the sagebrush. Our teachers imbued the rock with solemn significance, explaining its moniker as the "Register of the Desert." Over 5,000 names, dates, and messages, left by more than half a million pioneers who traversed the unforgiving Westward migration trails, were carved or painted onto its surface, a testament to their arduous journeys and their desire to leave an enduring sign of their passage. In 1961, recognizing its unparalleled historical importance, the state of Wyoming formally designated it a national historic landmark.

The sheer scale of Independence Rock is awe-inspiring. Rising 136 feet above the surrounding terrain, it rivals the height of a 12-story building. Its expanse covers a staggering 27 acres, with a circumference exceeding a mile, stretching 700 feet wide and 1,900 feet long. While the pioneers’ inscriptions are the most visibly prominent, the rock’s history stretches back much further. Fur trappers bestowed its current name in 1830, choosing it after celebrating Independence Day during a campout at its base. But long before any European-descended settlers, Indigenous tribes from the Central Rocky Mountains – including the Arapaho, Arikara, Bannock, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Crow, Kiowa, Lakota, Pawnee, Shoshone, and Ute – revered this very monolith. They left their own indelible marks, intricate carvings and petroglyphs, referring to it as Timpe Nabor, "The Painted Rock," reflecting a deep spiritual and cultural connection to the land that predates colonial settlement by millennia.

The pioneers’ varied descriptions of the rock, preserved in their journals and diaries, offer a fascinating glimpse into their perceptions. Wyohistory.org chronicles how John Ball, in 1832, likened it to "a big bowl turned upside down," estimating its size as "about equal to two meeting houses of the old New England Style." Lydia Milner Waters envisioned "Independence Rock was like an island of rock on the grassy plain," while Civil War soldier Hervey Johnson reported it looked "like a big elephant (up) to his sides In the mud." Others saw a huge whale or an apple cut in half and turned over, each description a unique reflection of their awe and imagination in the face of such a geological marvel.

As a geologist’s daughter, my fascination with Independence Rock was deeply rooted in its very formation. Geologically, it is a granite boss, a term that always elicited a chuckle, conjuring images of a rock dictating orders. In the lexicon of geology, however, a boss signifies an intrusive igneous feature – a massive body of molten rock, or magma, that pushed its way up from deep within the Earth’s crust. As this magma solidified beneath the surface, it formed a large, dome-shaped mass. Over eons, the softer overlying rock layers eroded away, exposing this resistant granite. Wyoming’s landscape is replete with such ventifacts, rocks meticulously sculpted by the ceaseless force of wind-driven sand, a process often termed "wind-faceting." At Independence Rock, this intricate dance with the elements began over 50 million years ago with exfoliation, where water seeped into its nascent fissures. The repeated cycles of freezing and thawing then pried apart the granite grains, causing thin sheets of crumbling rock to peel away. Rain and snow subsequently washed these fragments down, continuously exposing fresh rock beneath. Finally, around 15 million years ago, persistent windblown sand rounded its summit, completing its iconic dome shape and giving it the appearance we see today. This gradual, relentless shaping by natural forces underscores the immense power of geological time, where mountains rise and fall, and entire landscapes are remade.

In the process of recounting this geological narrative, I called my father, now 85, to verify my facts. Our childhood car trips were veritable classrooms of Earth science, filled with his explanations. He would point out a distant fault scarp or hand me an unassuming rock, then unveil its ancient story. I now observe in him a different kind of weathering; his face, a map of the years spent working outdoors, and his gait, a little less steady. Yet, his passion remains undimmed. He continues to participate in dinosaur digs, spending weeks in the field, much like the rocks he studies, constantly being shaped by the wind and sun. Joking, I tell him I, too, am a ventifact, believing the pervasive Wyoming wind has shaped my very being more than any other force.

Indeed, we are all intricately shaped by our environments, our parents, our education, and the countless journeys we undertake. For me, geology, the science of Earth’s physical structure and history, has perhaps been the most profound sculptor, growing up surrounded by rocks the size of skyscrapers, under an expansive sky that felt like a cosmic theater. In ninth grade, my teacher insisted we memorize the geologic time scale. In the car, between "Question Corner" and "New Word Light," I would chant, "Paleozoic, Mesozoic, Cenozoic!" then, "Jurassic, Triassic, Cambrian, Cretaceous!" – words as foreign and exotic as my French lessons. My dad would listen intently, registering every syllable, a steadfast presence. He was, in a profound sense, my own rock, a monolith upon whom I, too, left my mark. And in turn, I aspire to be the same for my own daughters.

The concept of deep time frequently occupies my thoughts. Humanity, a mere blip on this cosmic clock, joined the grand party only seconds before midnight. Independence Rock, the resilient turtle of the plains, will endure long after my own existence has faded, long after my father has passed into memory. And, paradoxically, I find immense comfort in this profound truth. This ancient granite boss has weathered the relentless elements, the ephemeral graffiti of human passage, and the boisterous celebrations of fur trappers, yet it still stands, resolute. I recognize that I do not need to carve my name upon a rock to affirm my fleeting existence. The humbling knowledge of a history so vast, so ancient, that unfolded long before us, offers not insignificance, but a peculiar kind of optimism. It reminds us that we each, in our own unique way, can serve as a steady monolith for others on their intricate journeys through time, imparting wisdom and resilience.

The thought of living on this Earth without my parents is an unimaginable prospect, yet I understand that day will inevitably arrive. While I am not suggesting my father will literally reside within the rocks I collect, in a more profound, metaphorical sense, his spirit and his enduring legacy will undoubtedly live on through the deep time that continues to shape us all.