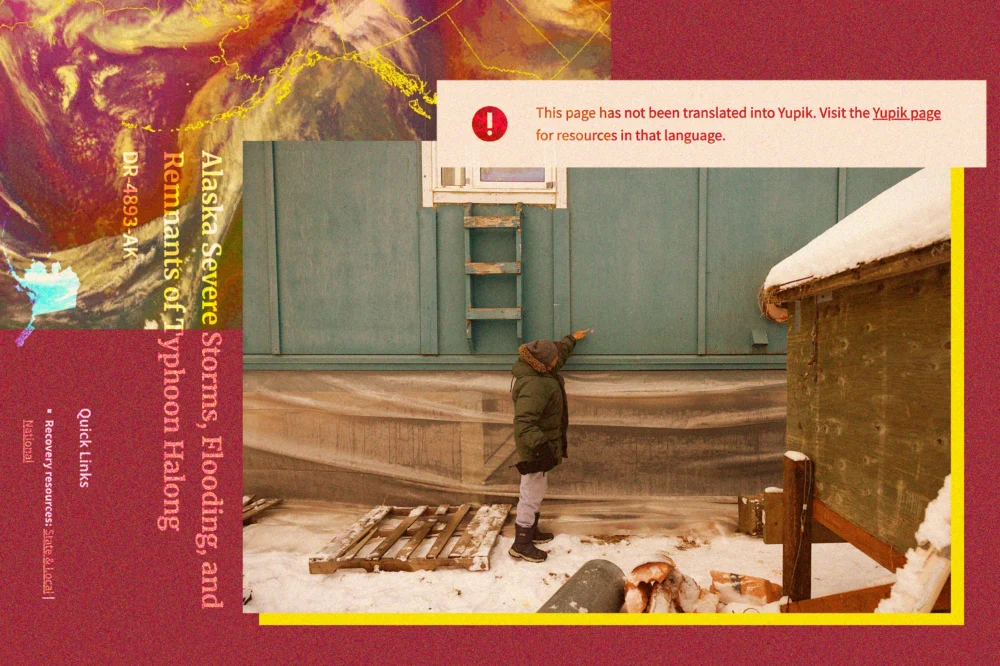

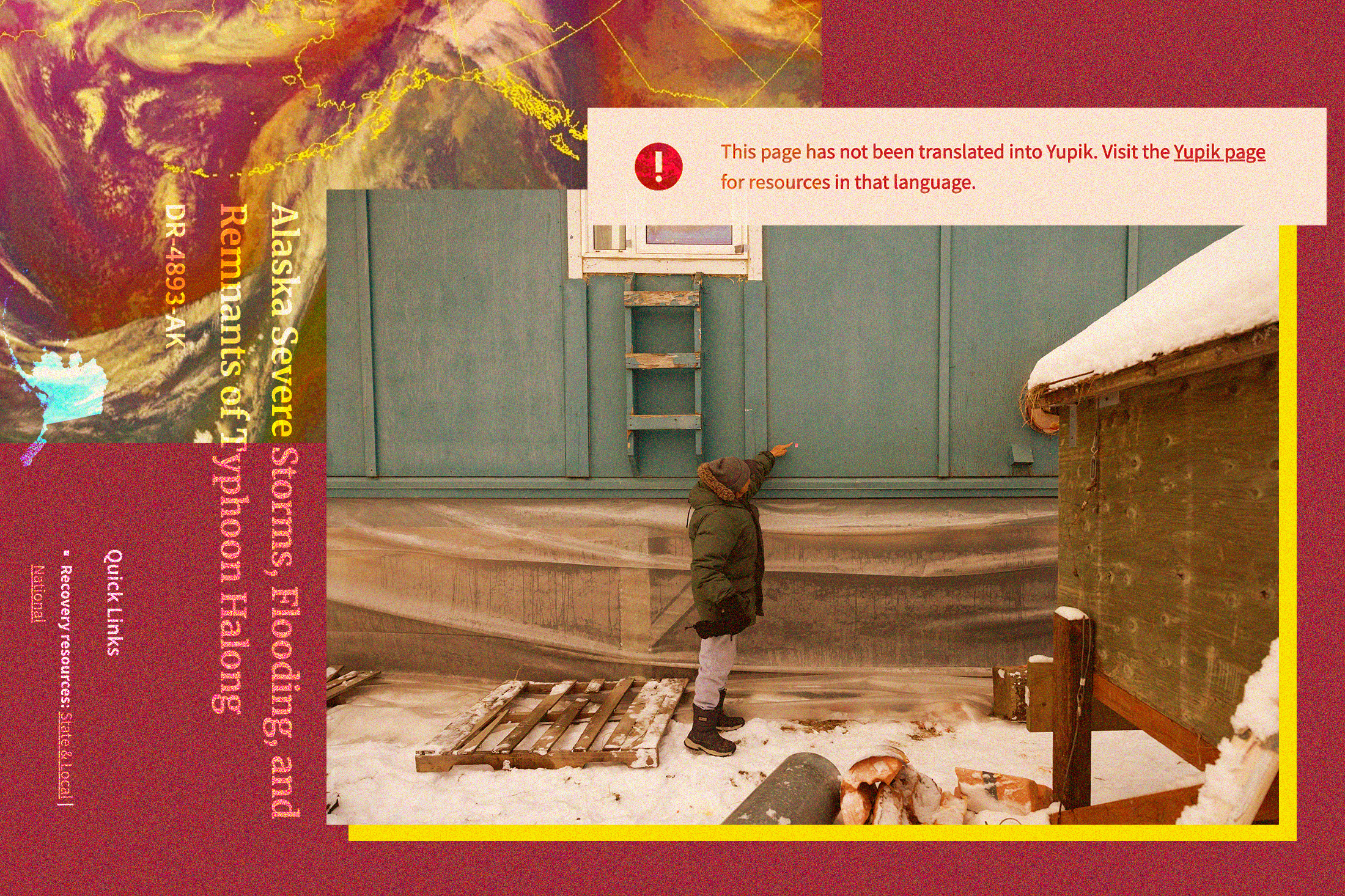

Following devastating storms that ravaged remote Western Alaska in 2022, exposing deep vulnerabilities in critical communication, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) engaged a California-based contractor to facilitate disaster aid for affected residents. The primary challenge centered on linguistic access: within the vast Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, a sprawling network of small Alaska Native communities, nearly half of the region’s 10,000 inhabitants primarily speak Yugtun, the Central Yup’ik dialect, often before learning English. Further north, approximately 3,000 individuals communicate in Iñupiaq. However, when local public radio journalists at KYUK attempted to review the translated application materials, they discovered the content to be utterly unintelligible, rendering vital information useless for those most in need. Julia Jimmie, a Yup’ik translator at KYUK, described the materials as "Yup’ik words all right, but they were all jumbled together, and they didn’t make sense," reflecting a profound disregard for the linguistic and cultural realities of the communities FEMA aimed to serve. This initial failure ignited a civil rights investigation into FEMA’s practices, eventually leading the original contractor, Accent on Languages, to reimburse the agency for the egregiously flawed translations.

Just three years later, the specter of inadequate translation looms once more over the same vulnerable region, which is now grappling with the aftermath of Typhoon Halong. The remnants of this powerful storm swept through in mid-October, displacing more than 1,500 residents and claiming at least one life in the village of Kwigillingok, underscoring the relentless impact of extreme weather events on these fragile Arctic ecosystems. As communities once again navigate the urgent need for disaster relief, the conversation around language access has taken a new, complex turn, spotlighting the controversial role of artificial intelligence (AI) in serving Indigenous communities.

Amidst the unfolding crisis, Prisma International, a Minneapolis-based company with a track record of over 30 contracts with FEMA in recent years, posted a job advertisement on October 21. The listing sought "experienced, professional Translators and Interpreters" for Yup’ik, Iñupiaq, and other Alaska Native languages, explicitly stating that successful applicants would be required to "provide written translations using a Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) tool." Prisma’s corporate website champions a hybrid approach, asserting that its tools "combine AI and human expertise to accelerate translation, simplify language access, and enhance communication across audiences, systems, and users." While FEMA declined to confirm in late October whether it planned to contract Prisma for the Alaska response, and Prisma itself remained unresponsive to inquiries, the job posting’s preference for candidates with experience translating for "emergency management agencies, e.g. FEMA," alongside a demonstrated connection to local Indigenous communities and knowledge of the recent storm, strongly suggested a forthcoming engagement. Indeed, several Yup’ik speakers in Alaska, including Julia Jimmie, confirmed being contacted by a Prisma representative who identified the company as "a language services contractor for the Federal Emergency Management Agency."

The prospect of AI integration in such a sensitive domain has ignited a complex debate within Indigenous communities and among technology experts. While some see the potential for AI to aid in the monumental task of language preservation, particularly for endangered dialects, others express deep skepticism regarding its capacity to accurately convey the intricate nuances of Indigenous languages and cultural knowledge. A primary concern revolves around the potential for AI to distort cultural information and, more critically, to undermine language sovereignty. Morgan Gray, a member of the Chickasaw Nation and a research and policy analyst at Arizona State University’s American Indian Policy Institute, articulates this apprehension: "Artificial intelligence relies on data to function. One of the bigger risks is that if you’re not careful, your data can be used in a way that might not be consistent with your values as a tribal community."

This issue is rooted in the broader concept of "data sovereignty," which asserts a tribal nation’s inherent right to define how its data is collected, managed, and utilized. This principle is increasingly central to international dialogues concerning Indigenous intellectual property and self-determination. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) enshrines the requirement for free, prior, and informed consent for the use of Indigenous cultural knowledge. UNESCO, the United Nations body responsible for cultural heritage, has also advocated for AI developers to respect tribal sovereignty in their interactions with Indigenous communities and their invaluable data. Gray emphasizes the imperative for tribal nations to possess comprehensive information about AI’s proposed application, the specific types of tribal data it would access, and sufficient time to evaluate its potential ramifications. Crucially, they must retain the unequivocal right to refuse, even when external entities present seemingly altruistic motives.

Despite FEMA’s stated commitment to improving its engagement with Alaska Native communities since the 2022 translation debacle—which included prioritizing Alaska-based vendors, mandating secondary quality-control reviews for all translations, and fostering continuous consultation with tribal partners—the agency’s policies regarding AI remain conspicuously vague. An email from a FEMA spokesperson did not directly address inquiries about specific AI regulations or safeguards for Indigenous data sovereignty, stating only that FEMA "works closely with tribal governments and partners to make sure our services and outreach are responsive to their needs." This lack of explicit policy is particularly concerning given Prisma’s extensive history of contracting with FEMA across more than a dozen states and its promotion of "LexAI" technology for multi-language disaster relief, even claiming to translate "rare Pacific Island dialects." While government records indicate Prisma has not previously contracted with the federal government specifically in Alaska, its expansion into the region highlights a critical gap in federal AI governance concerning Indigenous populations.

The practical implications of AI in translating complex languages like Yup’ik are a major source of apprehension among local experts. Julia Jimmie succinctly articulates this challenge: "Yup’ik is a complex language. I think that AI would have problems translating Yup’ik. You have to know what you’re talking about in order to put the word together." Unlike many European languages, Yup’ik is polysynthetic, meaning words are formed by adding multiple suffixes to a base root, creating highly specific and nuanced meanings that are often lost on AI models trained predominantly on vast datasets of less morphologically complex languages. This inherent structural difference, coupled with the scarcity of comprehensive, high-quality digital data for most Indigenous languages, means that AI-driven translation tools frequently produce inaccurate sentences, grammatical errors, and even entirely fabricated words, as academic studies have repeatedly shown.

Sally Samson, a Yup’ik language and culture professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, echoes this skepticism. Her concern extends beyond mere factual inaccuracies to the profound failure of AI to capture the essence of a Yup’ik worldview. "Our language explains our culture, and our culture defines our language," Samson asserts, highlighting how communication patterns in Yup’ik reflect deeply embedded cultural values, particularly respect. The inability of AI to grasp these intricate cultural frameworks risks not only misinformation but also a fundamental misrepresentation of Indigenous identity and ways of knowing.

While the challenges are significant, Indigenous software developers are actively exploring and leading innovative approaches to leverage AI for language revitalization. Examples include an Anishinaabe roboticist designing a robot to teach Anishinaabemowin, and a Choctaw computer scientist creating a chatbot for conversational Choctaw. The crucial distinction in these successful initiatives is that Indigenous people are at the helm, developing the AI models and making sovereign decisions about their application and ethical boundaries. This contrasts sharply with the scenario where external, non-Native companies introduce AI into Indigenous linguistic spaces without explicit, comprehensive consent and ownership agreements.

Crystal Hill-Pennington, who teaches Native law and business at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and consults for Alaska tribes, voices profound concerns about potential exploitation. She warns that if companies collect linguistic data from historically disadvantaged communities and then monetize that knowledge without sustained engagement with the originating community, it constitutes a problematic form of digital colonialism. This fear is not unfounded; Native communities possess centuries of experience with outsiders extracting and exploiting their cultural and intellectual property. A recent precedent emerged in 2022 when the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council famously banished a nonprofit that, after years of collaboration with Lakota elders on language preservation, copyrighted the shared materials and attempted to sell them back to tribal members as textbooks. Hill-Pennington underscores the central question in the age of AI: "who ends up owning the knowledge that they’re scraping?"

As AI technology rapidly advances, standards for its ethical deployment and respect for Indigenous cultural knowledge are also evolving. Hill-Pennington acknowledges that some companies may still be unfamiliar with the critical importance of informed consent and the concept of data sovereignty. However, she stresses that these standards are becoming increasingly indispensable, particularly for entities collaborating with federal agencies that are bound by executive orders mandating authentic consultation with Indigenous peoples in the United States. In the context of disaster response, where urgent needs intersect with deep cultural and linguistic heritage, overlooking these fundamental principles is no longer an option.