For generations, dominant academic and popular narratives in North America have propagated the belief that humans first migrated into the continent approximately 12,000 to 13,000 years ago. This hypothesis, known as the "Clovis-first" theory, posits that early peoples traversed a land bridge across the Bering Strait from Asia during the late Pleistocene epoch, at the close of the last ice age. Named after distinctive spearpoints discovered near Clovis, New Mexico, this framework became deeply entrenched in archaeological and anthropological discourse, forming the bedrock of American prehistory. However, Indigenous oral histories consistently offer a starkly different account, asserting a much earlier, unbroken presence on these lands, often extending beyond the grasp of Western chronological frameworks. The phrase "time immemorial" thus serves as a powerful, succinct rejoinder, affirming this deep Indigenous past without being drawn into often-contentious debates over precise dates and numerical figures. It declares an enduring connection to the land that precedes colonial memory and challenges the very foundation of settler legitimacy.

Harvard history professor Philip J. Deloria (Yankton Dakota descent) explains the profound meaning embedded in the phrase, stating, "I take it to mean the deepest possible kind of human memory. Beyond recorded history, beyond oral tradition, beyond oral memory, into what we call the deep past." This "deep past" directly confronts the Clovis-first narrative, which, despite its scientific veneer, has been wielded as a political tool. By portraying Indigenous peoples as relatively recent arrivals, not fundamentally different from later European colonizers in their migratory patterns, the narrative conveniently erodes the moral and legal claims of Indigenous land title. It subtly justifies settler colonialism, presenting a continent open for discovery rather than one already inhabited by sophisticated, long-established societies. The elegance of the Clovis-first theory, with its seemingly clear correlation between early stone tools, melting glaciers, and the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna, made it an attractive and persistent scientific canon. However, as Deloria notes, its greatest strength was also its fatal flaw: any credible evidence of human presence prior to Clovis would dismantle the entire construct.

And indeed, such evidence has emerged, progressively cracking the monolithic edifice of the Clovis-first story. Since the mid-20th century, archaeologists have unearthed numerous sites across the Americas that unequivocally demonstrate human occupation predating the Clovis era. One of the earliest and most controversial challenges came in 1963 from the Calico Early Man Site in California’s Mojave Desert. Here, world-renowned archaeologist Louis Leakey, celebrated for his discoveries in East Africa, identified what appeared to be stone tools and flintknapping debris dating back over 20,000 years, with some estimates reaching hundreds of thousands of years. Despite Leakey’s immense credibility, his findings were met with fierce resistance, leading to professional ostracization and derision. The prevailing scientific establishment largely dismissed the Calico artifacts, often attributing their form to natural geological processes rather than human modification.

Paulette Steeves (Cree-Métis), an archaeology professor at Algoma University and author of The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere, argues that the academic community has not merely ignored but actively suppressed archaeological evidence of pre-Clovis humans in the Americas for over a century. This suppression, she contends, stems from deeply embedded biases and systemic racism within the scientific field. The resistance encountered by Leakey was not an isolated incident; for decades, publishing research on pre-Clovis sites was considered "career suicide" for archaeologists, leading to many significant findings being marginalized or dismissed as pseudoscience. This scientific gatekeeping effectively maintained the colonial narrative by silencing dissenting voices and evidence.

However, the weight of accumulating evidence has become undeniable. Sites like Monte Verde in Chile, with its well-preserved artifacts dating back at least 14,500 years, provided some of the earliest conclusive proof of pre-Clovis habitation in South America. Similarly, North American sites such as Cactus Hill in Virginia (over 18,000 years old), the Gault site in Texas (up to 16,000 years old), and Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania (over 16,000 years old) have presented robust archaeological data challenging the Clovis barrier. More recently, discoveries like Chiquihuite Cave in Mexico, yielding evidence of human occupation dating back approximately 26,000 years, and the highly controversial Hueyatlaco site, also in Mexico, with potential dates far exceeding 200,000 years, have further destabilized the long-held dogma. These sites, often meticulously excavated and subjected to rigorous dating techniques, collectively paint a picture of a far more ancient and complex peopling of the Americas than previously acknowledged.

A pivotal moment arrived in 2021 when Science magazine published a report confirming 20,000-year-old human footprints discovered near White Sands, New Mexico. This publication, in one of the world’s most prestigious scientific journals, signaled a significant shift in institutional acceptance of pre-Clovis human habitation. The report’s authors explicitly stated that these findings "confirm the presence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum," undeniably establishing that "someone" was present during the last ice age, long before the makers of the Clovis spearpoints. This breakthrough validated what Indigenous peoples have asserted for millennia, lending scientific credence to their deep historical narratives.

Beyond archaeology, other academic disciplines offer compelling support for the "time immemorial" concept. Linguists, for example, have observed the immense diversity and complexity of language families across the Americas, positing that such extensive diversification would have required at least 30,000 years, if not significantly longer, to develop from a common ancestral language. This linguistic depth implies human presence stretching far beyond the Clovis timeline. Similarly, DNA research has uncovered intricate genetic links, such as those between some Indigenous South American populations and Austronesian peoples, suggesting ancient trans-Pacific migrations that complicate the singular Bering Strait narrative and point to multiple, earlier waves of arrival.

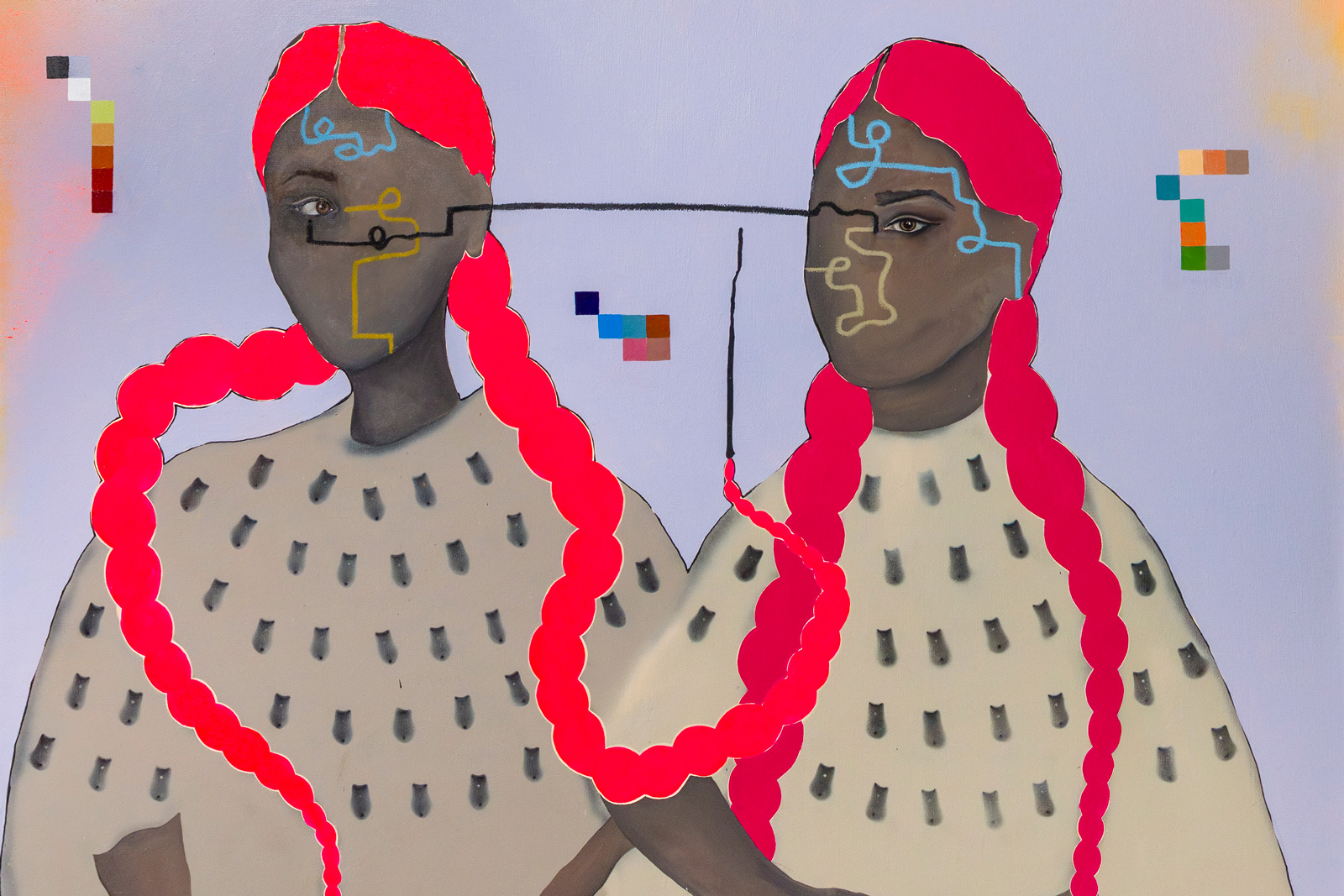

Crucially, these scientific revelations increasingly align with the rich tapestry of Indigenous oral histories. Often dismissed by Western academia as mere legends or myths due to their non-written format, oral traditions are, in fact, sophisticated systems of knowledge transmission. As Deloria highlights, these histories are meticulously memorized under the guidance of elders and retold with a profound sense of responsibility to the community, preserving detailed accounts of ancestral migrations, cultural practices, and significant events across vast spans of time. They represent a living archive, continuously maintained and passed down through generations.

The physical monuments scattered across North America further buttress these older timelines and oral histories, bearing silent witness to the continent’s profound past. The weathered remains of earthen mounds at Cahokia and Poverty Point along the Mississippi River, once supporting wooden temples and forming the nuclei of thriving cities, reveal sophisticated agricultural and social structures that predate European arrival by millennia. The Hohokam canals in Arizona’s Salt River Valley, an intricate network of hundreds of miles of agricultural irrigation, showcased technological prowess that Popular Archaeology notes "rivaled the ancient Roman aqueducts." Similarly, the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, massive geometric earthen constructions in the Ohio River Valley, demonstrate advanced astronomical knowledge, aligning precisely with solar and lunar cycles. These monumental achievements, which Philip Deloria refers to as evidence of "North American Classical civilizations," reveal societies with complex governance, advanced engineering, and deep spiritual connections to their environment. Yet, settler narratives often omit these achievements from classroom curricula and popular imagination, reserving the term "classical" almost exclusively for ancient Western European cultures. This historical omission perpetuates a hierarchy of civilizations, denying North American Indigenous cultures their rightful place among the world’s great ancient societies.

The ongoing struggle to validate Indigenous histories carries significant implications beyond academic debate. The denial of deep Indigenous presence fuels hateful comments and resistance to Indigenous progress, reflecting a colonial mindset that struggles to acknowledge the rich, complex histories that existed long before the "New World" was "discovered." Challenging the Clovis-first story and the Bering land bridge theory fundamentally erodes the legitimacy of the colonial empire and the narratives it props up, including white supremacy and American exceptionalism. Recognizing that Indigenous peoples were here long before the arrival of Europeans, with their own intricate civilizations, systems of governance, and profound connections to the land, dismantles the myth of an empty continent awaiting settlement.

The power of "time immemorial" lies in its ability to transcend the limitations of colonial frameworks and numerical arguments. It sweeps aside the need to "debate" precise dates with those invested in denying Indigenous antiquity, making space for ancestral voices to speak from the deep past. As Paulette Steeves eloquently states, "It’s really important right now to decolonizing settler minds, to decolonizing education, and to decolonizing ourselves." By embracing "time immemorial," Indigenous peoples reclaim their narrative, asserting a continuous presence and cultural resilience that defies centuries of oppression. It is a declaration that acknowledges not just a distant past, but a continuous cultural existence that will endure long into the future, prophesying a future vision of the continent that transcends the colonized imagination.