The slow migration of dunes in the Gran Desierto de Altar, east of where the Colorado River once met the Gulf of California, serves as a tangible illustration of geological processes that shape our planet over vast timescales. These subtly shifting sand formations, with grains tumbling down their slopes, mirror the incremental deposition that formed ancient rock layers like the Coconino sandstone in the Grand Canyon, whose sweeping diagonal lines reveal the direction of winds from 280 million years ago. This principle, often summarized by geologists as "the present is the key to the past," underscores the interconnectedness of observable phenomena and deep history. However, the rock record also chronicles dramatic, planet-altering events, including the "Big Five" mass extinctions that fundamentally reshaped life and landscapes. Understanding this interplay of gradual change and catastrophic disruption offers a crucial lens through which to view our present and anticipate our future, compelling us to grapple with concepts like "deep time" and the immense durations over which geological formations accrue.

John McPhee, a celebrated writer for The New Yorker, was instrumental in popularizing the concept of "deep time" with his 1981 book, Basin and Range, which is now best experienced within his 1999 Pulitzer Prize-winning anthology, Annals of the Former World. Though originally published during the Reagan administration and later revised, McPhee’s narratives about North America’s billions of years of history, as interpreted by geologists from the rocks themselves, retain remarkable relevance. McPhee’s approach involved accompanying geologists on journeys across the continent, notably along Interstate 80 from New Jersey to Nevada, capturing the essence of geological discovery.

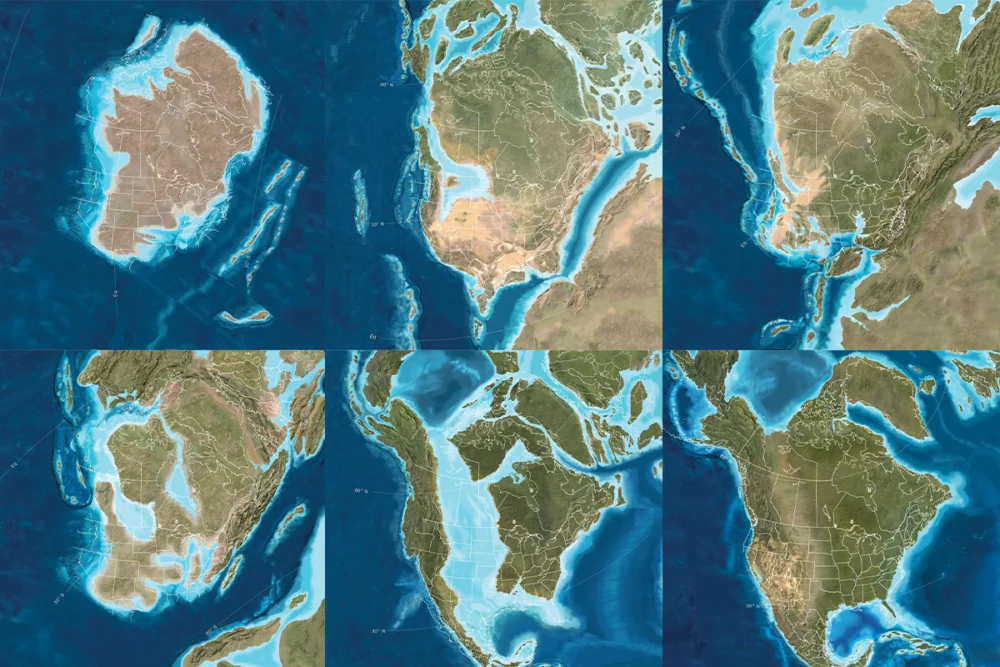

In the western United States, particularly Utah and Nevada, McPhee delves into the formation of mountain ranges and intervening basins, a pattern of alternating elevated and depressed landmasses. Geologists explain this phenomenon as a result of tectonic activity, where faulting creates basins that are subsequently filled with sediments—a process, though simplified, that speaks to millions of years of geological evolution. McPhee highlights how the North American continent is undergoing a process of "being literally pulled to pieces" between the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada, a scenario that has precedent in Earth’s history, such as the rifting of the supercontinent Pangaea approximately 200 million years ago, which eventually led to the formation of the Atlantic Ocean. This geological perspective prompts contemplation on future continental configurations, such as the potential for a new sea to emerge between Nevada and California.

McPhee’s narrative is punctuated by fascinating detours, including a visit to an abandoned silver mine in Nevada. Here, he learns about the historical exploitation of mineral resources, where 19th-century miners extracted the richest silver veins, potentially leaving behind vast quantities of lower-grade ore that might still hold significant economic value. His excursions also lead him to reflect on the human perception of time, noting that our natural inclination is to think in terms of a few generations, a stark contrast to the geological epochs geologists routinely consider. McPhee’s work serves as an accessible introduction to geology, enabling readers to appreciate how scientists can reconstruct and visualize ancient landscapes and events that no human eye has ever witnessed, from volcanic archipelagos to vast, now-vanished continental formations.

Science journalist Laura Poppick, in her July 2025 book, Strata: Stories from Deep Time, offers a complementary exploration of Earth’s history. While sharing McPhee’s meticulous attention to detail, Poppick organizes her narrative thematically around fundamental elements of Earth’s evolution: air, ice, mud, and heat. Her investigation into rocks dating back 2 to 3 billion years reveals crucial insights into the initial oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere. By examining iron-rich rocks from a period of global anoxia, Poppick illustrates that for roughly half of Earth’s existence, the atmosphere lacked significant oxygen, a condition that predated and ultimately enabled the development of complex life as we know it. The oxygen-rich air that subsequently emerged facilitated the formation of iron, a metal indispensable for modern technologies, from vehicles and appliances to medical devices and aircraft.

Poppick also examines the profound impact of mass extinction events on the trajectory of life. She details two of the "Big Five" major extinction events: one occurring approximately 250 million years ago and another roughly 50 million years later. Unlike the extinction event attributed to an asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs, these earlier catastrophes appear to have been triggered by massive volcanic eruptions. These eruptions occurred in geologically sensitive areas where magma rose from the mantle directly beneath vast deposits of fossil fuels, igniting them and releasing immense quantities of carbon dioxide, toxic hydrocarbons, and ozone-depleting gases. This historical account of ecological collapse offers a potent parallel for understanding contemporary climate change and potential pathways toward mitigation.

The book also explores the world of the dinosaurs, including the seemingly endless summers of the Mesozoic Era, which models suggest were 14 to 25 degrees Celsius (25 to 45 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than today. Poppick joins scientists in Wyoming searching for fossil evidence of the largest terrestrial animals ever to exist—the long-necked sauropods like Diplodocus, Brontosaurus, and Apatosaurus. The focus of this research extends beyond the skeletal remains to the ancient ecosystems that supported these colossal herbivores and how these environments, along with their inhabitants, evolved over time. These studies often center on formations like the Morrison Formation, a vast layer of sedimentary rock stretching from New Mexico to Montana, which has yielded an unparalleled abundance of dinosaur fossils. The deposition of these rocks over approximately 9 million years provides a detailed chronicle of dinosaurian history, a timescale that Poppick notes is comparable to the 12 million years of evolution that led from a common ancestor to modern humans, gorillas, and chimpanzees. Scientists analyzing the Morrison Formation’s strata seek to understand how sauropods and other dinosaurs thrived in the warm Jurassic climate, suggesting that a deeper understanding of these ancient periods enhances our appreciation for Earth’s resilience and capacity to support life under extreme conditions.

To truly immerse oneself in the Jurassic world, Riley Black’s February 2025 book, When the Earth Was Green, offers a captivating experience. A science writer and paleontologist, Black blends scientific data with artistic prose to bring ancient ecosystems to life. Each chapter is presented as a vignette, accompanied by an appendix that elucidates the scientific basis for the narrative, distinguishing between established knowledge, informed speculation, and the author’s imaginative interpretations.

Black transports readers to Utah 150 million years ago, moving beyond the fossil sites to envision a vibrant, prehistoric landscape. He vividly depicts an Apatosaurus foraging in a lush woodland, consuming an abundance of horsetail plants and an ancient relative of the ginkgo tree. The sauropod’s remarkable size and long neck provided an advantage, allowing it to access food from both the forest floor and the high canopy, while also offering protection from predators. Black emphasizes that the very existence of such gigantic herbivores was a testament to their unique habitat, characterized by towering conifers and a dense understory of ferns and cycads. This intricate relationship between herbivores and the plant life that sustained them is described as an "evolutionary dance." Black’s earlier work, The Last Days of the Dinosaurs, meticulously detailed the fifth major extinction event on a second-by-second, day-by-day basis. In contrast, When the Earth Was Green focuses more on the co-evolutionary dynamics between ancient flora and fauna, exploring how their intertwined stories became preserved in the geological record.

Reading McPhee offers a sense of accompanying a charismatic, albeit eccentric, geologist on a road trip, filled with insightful observations and moments of enthusiastic exclamation. Poppick’s approach draws readers into the scientific process itself, inviting participation in field studies and laboratory explorations, revealing the engaging nature of scientific inquiry. Black, with his evocative descriptions, immerses readers in dreamlike, long-vanished worlds, using imagination grounded in scientific understanding to make deep time palpable. As Poppick suggests, our planet seems to be communicating a need for reflection on its past. Each of these authors provides a unique pathway into geological history, encouraging a deeper understanding of our place within the vast continuum of Earth’s existence.