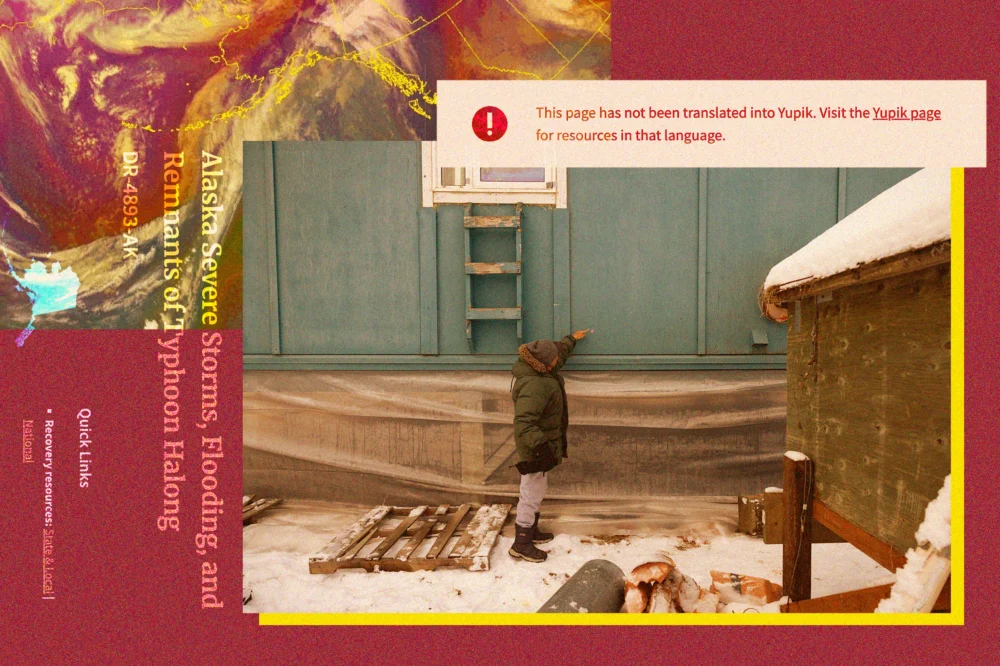

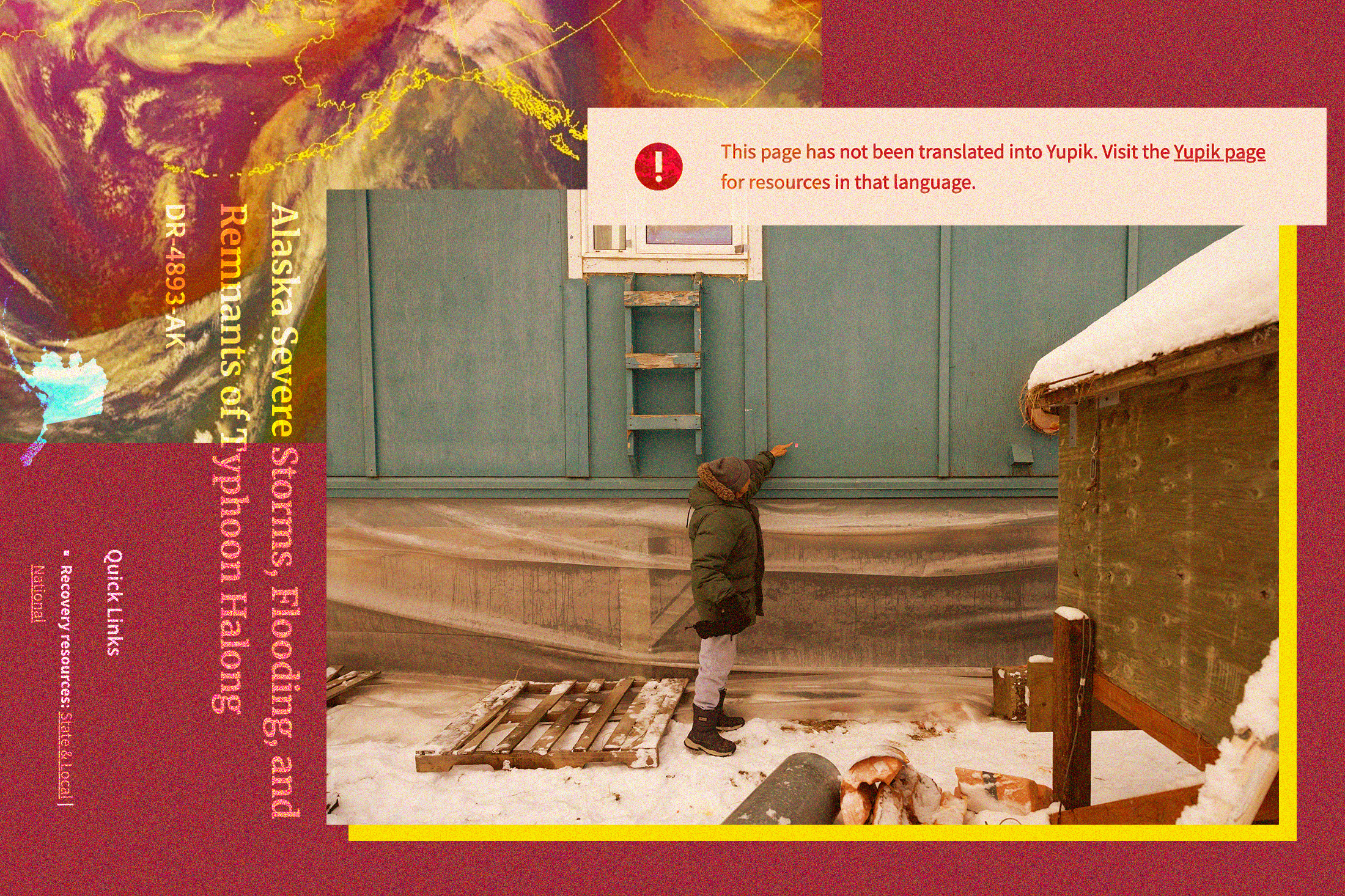

As Western Alaska grapples with the devastating aftermath of Typhoon Halong, which displaced over 1,500 residents and claimed at least one life in the village of Kwigillingok in mid-October, the critical challenge of providing accessible disaster relief has once again brought the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) under intense scrutiny. This time, the focus is not merely on translation failures but on the controversial role of artificial intelligence (AI) in communicating with Indigenous communities, resurrecting deep-seated concerns about cultural preservation and language sovereignty. The current crisis follows a precedent set in 2022, when historic storms ravaged remote Alaskan villages, prompting FEMA to contract a California-based firm, Accent on Languages, to translate aid applications. Their mission was to bridge the linguistic divide in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, a region where nearly half of the approximately 10,000 Alaska Native residents speak Yugtun, the Central Yup’ik dialect, as their first language, often before English. Farther north, an estimated 3,000 individuals communicate in Iñupiaq.

However, the translations provided by Accent on Languages proved to be a profound failure. Local public radio station KYUK’s journalists, alongside Yup’ik translator Julia Jimmie, discovered the material was utterly incomprehensible. Jimmie, a fluent Yup’ik speaker, described the documents as a jumble of Yup’ik words that made no sense, reflecting a disheartening assumption that the language was no longer actively spoken or understood by its people. This egregious error not only hindered access to vital financial assistance but also conveyed a profound lack of respect for the linguistic heritage and intellectual capabilities of the communities FEMA was meant to serve. The incident ignited a civil rights investigation into FEMA’s practices and ultimately led to the California contractor reimbursing the agency for its substandard work. In response, FEMA ostensibly revised its policy, committing to using "Alaska-based vendors" for Alaska Native language services, with a preference for those within disaster-impacted areas, and implementing a secondary quality-control review for all translations, alongside continuous consultation with tribal partners.

Despite these purported improvements, the latest disaster has reignited the same anxieties, albeit with a modern twist. Prisma International, a Minneapolis-based company with a track record of over 30 contracts with FEMA in recent years, posted an advertisement on October 21 seeking "experienced, professional Translators and Interpreters" for Yup’ik, Iñupiaq, and other Alaska Native languages. This job posting appeared just one day before the Trump administration approved a disaster declaration for Typhoon Halong. Prisma’s corporate website proudly touts its approach of combining "AI and human expertise to accelerate translation, simplify language access, and enhance communication." The job description for the Alaska Native language translators specifically mentioned the requirement to "provide written translations using a Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) tool," signaling the imminent integration of AI into these sensitive communication efforts.

While FEMA remained tight-lipped in late October about whether it had formally contracted Prisma for the Alaska response, and Prisma itself did not respond to inquiries, multiple Yup’ik speakers in Alaska confirmed they had been contacted by Prisma representatives. These representatives explicitly identified Prisma as "a language services contractor for the Federal Emergency Management Agency." Julia Jimmie, who had previously exposed the 2022 translation fiasco, was among those contacted. She expressed a willingness to translate for FEMA but harbored significant reservations about collaborating with Prisma, particularly concerning the use of AI.

The burgeoning integration of AI into various facets of daily life, including language services, has elicited a complex mixture of excitement and apprehension within Indigenous communities globally. While many Native tech and cultural experts recognize AI’s potential, especially for language preservation and revitalization efforts, they simultaneously caution against the inherent risks of cultural distortion and threats to language sovereignty. Morgan Gray, a member of the Chickasaw Nation and a research and policy analyst at Arizona State University’s American Indian Policy Institute, articulates a core concern: "Artificial intelligence relies on data to function. One of the bigger risks is that if you’re not careful, your data can be used in a way that might not be consistent with your values as a tribal community."

This concern is amplified by the concept of "data sovereignty," which asserts a tribal nation’s inherent right to define how its data is collected, used, and managed. This principle is increasingly central to international discourse on Indigenous intellectual property rights. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) explicitly mandates free, prior, and informed consent for the utilization of Indigenous cultural knowledge. UNESCO, the UN body safeguarding cultural heritage, has similarly urged AI developers to respect tribal sovereignty when engaging with Indigenous communities and their invaluable data. Gray underscores the necessity for tribal nations to possess comprehensive information regarding AI deployment, the specific types of tribal data involved, ample time for consideration of potential impacts, and critically, the unequivocal right to refuse any external entity’s use of their information, irrespective of altruistic intentions. The lack of clarity on whether Prisma has engaged with tribal leadership in the Y-K Delta, with the Association of Village Council Presidents not responding to requests for comment, exacerbates these concerns. Prisma’s website mentions an "AI Responsible Usage Policy," allowing clients to opt for human-only translations, yet the specifics of this policy remain opaque and inaccessible to the public.

FEMA’s broader stance on AI remains ambiguous. While the agency asserts its commitment to working closely with tribal governments to ensure responsive and accessible services, its email communications have conspicuously avoided directly addressing questions regarding specific policies for AI regulation or the protection of Indigenous data sovereignty. This silence leaves a critical void, particularly as FEMA’s contracts with Prisma extend across more than a dozen states. Prisma’s own case studies, such as one highlighting its "LexAI" technology’s role in providing multi-language disaster relief information, including "rare Pacific Island dialects," underscore its reliance on AI for diverse linguistic contexts. While Prisma has worked with other federal agencies, its current foray into Alaska represents a new frontier for its AI-driven services within the state.

At the heart of the local concerns is the fundamental question of AI’s practical capability to accurately translate complex Indigenous languages like Yup’ik. Julia Jimmie articulates this challenge succinctly: "Yup’ik is a complex language. I think that AI would have problems translating Yup’ik. You have to know what you’re talking about in order to put the word together." Unlike many European languages, Yup’ik is a polysynthetic language, where words are formed by combining multiple morphemes, making a single word equivalent to an entire English sentence. This intricate agglutinative structure, coupled with the scarcity of large, well-curated digital text corpora for Indigenous languages, poses immense challenges for AI models, which typically thrive on vast datasets. Consequently, AI has a documented poor track record with Indigenous languages, often producing grammatically incorrect sentences or even entirely fabricated words.

Sally Samson, a Yup’ik professor of language and culture at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, expresses profound skepticism regarding AI’s ability to master Yugtun syntax, which diverges significantly from English. Her concern transcends mere misinformation; she fears that AI will inevitably fail to capture the profound nuances of the Yup’ik worldview. "Our language explains our culture, and our culture defines our language," Samson emphasizes. "The way we communicate with our elders and our co-workers and our friends is completely different because of the values that we hold, and that respect is very important." The language is not merely a communication tool but a living repository of cultural knowledge, ethics, and societal values.

While commercial entities like Prisma explore AI’s potential, Indigenous software developers are actively pioneering their own AI solutions to address the shortcomings around Native languages, primarily for revitalization. An Anishinaabe roboticist has developed a robot to aid children in learning Anishinaabemowin, while a Choctaw computer scientist created a chatbot for conversational Choctaw. The crucial distinction here lies in the locus of control: these initiatives are Indigenous-led, ensuring that the technology serves community-defined goals and values, safeguarding linguistic and cultural integrity.

The specter of exploitation looms large. Crystal Hill-Pennington, who teaches Native law and business at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and provides legal consultation to Alaska tribes, voices deep apprehension about the potential for exploitation if AI models are trained on the invaluable work of Indigenous translators, only to be subsequently leveraged by non-Native companies for profit without sustained engagement or benefit to the originating communities. Indigenous communities bear centuries of experience with the extraction and exploitation of their cultural knowledge. A stark recent precedent emerged in 2022 when the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council took the unprecedented step of banishing a nonprofit organization that, after years of receiving cultural knowledge from Lakota elders, copyrighted the material and attempted to sell it back to tribal members in textbooks. This incident underscores the urgent need for robust protections against intellectual property theft in the digital age. Hill-Pennington warns that the proliferation of AI by private corporations adds another layer of complexity to these ongoing discussions: "The question is, who ends up owning the knowledge that they’re scraping?"

Standards governing AI and Indigenous cultural knowledge are evolving rapidly, mirroring the pace of technological advancement itself. Hill-Pennington acknowledges that some companies utilizing AI may still be unfamiliar with the critical expectation of informed consent and the fundamental concept of data sovereignty. However, she asserts that these standards are becoming increasingly indispensable, especially for entities collaborating with federal agencies that are bound by executive orders mandating authentic consultation with Indigenous peoples in the United States. The challenge for FEMA and its contractors is to navigate this complex ethical and technical landscape, ensuring that the urgency of disaster response does not override the fundamental rights to language, culture, and self-determination for Alaska Native communities. Effective, culturally competent communication is not merely a logistical challenge but a matter of justice and dignity in the face of escalating climate-induced disasters.