In Tucson, Arizona, a profound ecological movement has been quietly gaining momentum for decades, shifting the focus from merely restoring degraded habitats to actively reimagining and reconnecting with local landscapes by embracing their inherent imperfections. This innovative approach, often referred to as "reconciliation ecology," emerged from the environmental consciousness ignited in the 1960s and the subsequent conservation and ecological restoration efforts of the 1970s and 1980s. Today, instead of discussing the "restoration" of an urban stretch of a river corridor, practitioners advocate for "reconciliation," a concept coined in 2003 that aims to increase biodiversity within human-dominated landscapes, essentially offering a form of conservation for the Anthropocene.

Angel Antonio Breault, a fourth-generation Tucsonan, grew up near the upper reaches of the region’s floodplain, perceiving it simply as a ditch. However, his studies in ecology and his Sunday visits to the Santa Cruz River to observe birds and wildflowers sparked a deeper personal connection to the waterway. This evolving relationship inspired him to establish the community initiative "Reconciliation on the Santa Cruz River," which diverged from earlier environmental campaigns by prioritizing a reimagining of human-land relationships over solely focusing on landscape restoration.

The roots of this movement trace back to the 1960s, a period marked by growing awareness of air and water pollution and environmental disasters like oil spills and the widespread use of pesticides, which spurred local environmentalists into action. By this time, unchecked development had led to extensive groundwater and surface water pumping, resulting in rivers and streams drying up for much of the year. While Phoenix, two hours to the north, continued its rapid expansion with new housing developments, local non-profits and community groups in Tucson formed coalitions to advocate for slower growth within the city. Within a decade, Tucson had proactively purchased farmland west of its city limits, removing it from use to alleviate pressure on groundwater pumping. This strategic move paved the way for the consolidation of smaller water systems into Tucson Water, a city-managed entity with a valley-wide infrastructure and a unified approach to water resource management.

Following these foundational steps, the city launched its pioneering "Beat the Peak" campaign in 1977, aiming to raise public awareness about peak water usage and encourage the use of reclaimed wastewater for landscaping. By 1984, Tucson had become one of the first cities in the nation to recycle treated wastewater for irrigating parks and golf courses, demonstrating a commitment to innovative water management. Environmental activists, who had long championed slower development, built a coalition that successfully advocated for the protection of habitats for 44 vulnerable, threatened, and endangered species, the establishment of bond-funded land conservation programs, and a robust system for preserving open spaces and mitigating impacts on vital riparian habitats. These concerted efforts culminated in the Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan, officially adopted by the Pima County Board of Supervisors in October 1998, with the dual objectives of safeguarding endangered species and imposing significant development restrictions. Over time, the plan has expanded its scope to encompass environmental restoration, wildlife crossings, and rainwater harvesting.

The 200-mile-long Santa Cruz River, which flows through Tucson on its journey from northern Mexico, serves as a powerful example of how Tucson residents have pioneered urban conservation. The river’s course through Tucson was profoundly impacted by early 20th-century development, including overgrazing, groundwater depletion, and infrastructure construction, which devastated its riverbed. By the 1950s, the Santa Cruz River segment through Tucson had completely dried up. Decades later, local ecologists, much like their predecessors, recognized the urgent need to advocate for the river and the communities reliant on it. However, Breault and his contemporaries saw no feasible way to restore the trash-laden, drought-ravaged Santa Cruz to conventional scientific or conservationist standards. Their vision was different: reconciliation.

"I see the Santa Cruz as a portal," Breault explained, describing it as a pathway for people to explore authentic relationships they already possess with the natural world. He believes that participatory programs are the most effective means of engaging the public, emphasizing that individuals do not require constant guidance. Breault is convinced that people connect best with nature when they discover their own methods, regardless of how severely the environment has been impacted, utilized, or abused in the past. Even degraded and desiccated ecosystems like the Santa Cruz, he argues, retain the capacity to sustain life and thrive.

In late 2017, a significant development occurred when the endangered Gila topminnow was discovered downstream from the Nogales International Wastewater Treatment Plant. To aid in replenishing the aquifer and its riparian habitat, Tucson Water began diverting up to 10 million liters of recycled water into the river, south of the city center. A collaborative team of scientists from the Arizona Game and Fish Department and the University of Arizona carefully collected over 700 Gila topminnows from upstream and transported them to a release point near downtown Tucson, where the previously polluted and dry riverbed was being revitalized.

This initiative, undertaken in 2020, has led to the river now flowing modestly for approximately one mile near downtown Tucson. While some sections are ephemeral, others are perennial, creating a dynamic and ever-changing riparian landscape. Following heavy monsoon rains, the river flows freely, but even without the monsoon season, the continuous discharge of effluent is sufficient to foster the resurgence of wetlands and marshes. Cottonwood trees, absent for over six decades, are reappearing, the Gila topminnow is successfully reproducing, and approximately 40 other native animal and plant species have returned to the area.

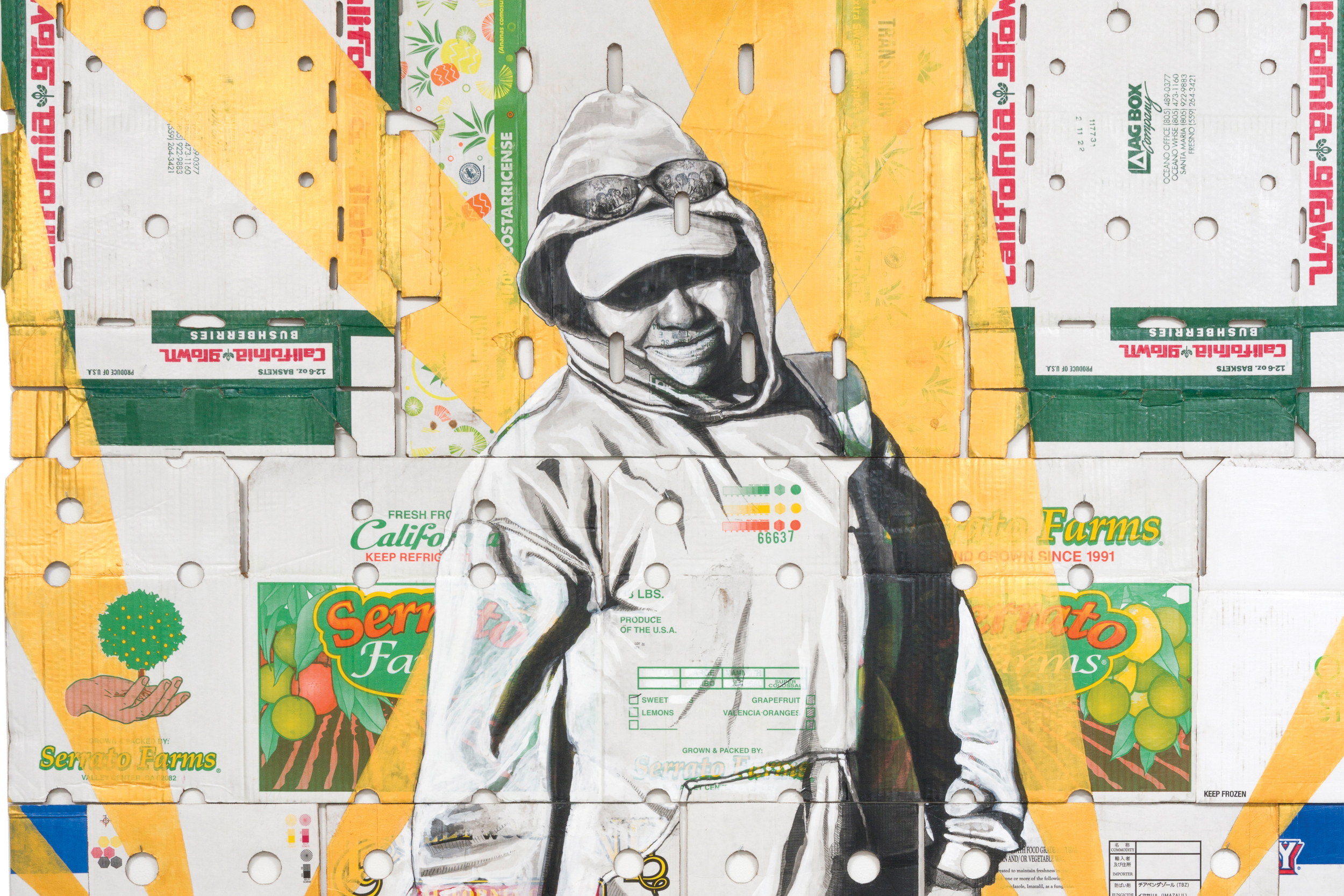

The return of nature has also brought people back to the river, whether participating in organized cleanups, conducting impromptu removals of invasive plants, or simply observing wildlife. "Line up," Breault encouraged, suggesting that individuals should engage in activities that align with their strengths, such as storytelling. He outlined upcoming gatherings planned along the river, ranging from writing workshops and art-making sessions to interpretive nature walks, alongside other events he has heard about. "We don’t have to do everything," he stated, believing that the river itself understands. "We just have to be there together." This collaborative and community-driven approach embodies the spirit of reconciliation ecology, transforming a neglected urban waterway into a vibrant testament to human and ecological coexistence.