Born in Oaxaca, Mexico, in 1977, Narsiso Martinez immigrated to the United States at the age of 20, embarking on a journey that would lead him to earn a master of fine arts degree in drawing and painting from California State University, Long Beach. His impactful artwork, recognized both locally and internationally, resides in the esteemed collections of institutions such as the Hammer Museum, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, the University of Arizona Museum of Art, the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon, and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Martinez, who lives and works in Long Beach, California, recently shared insights into his artistic practice with High Country News.

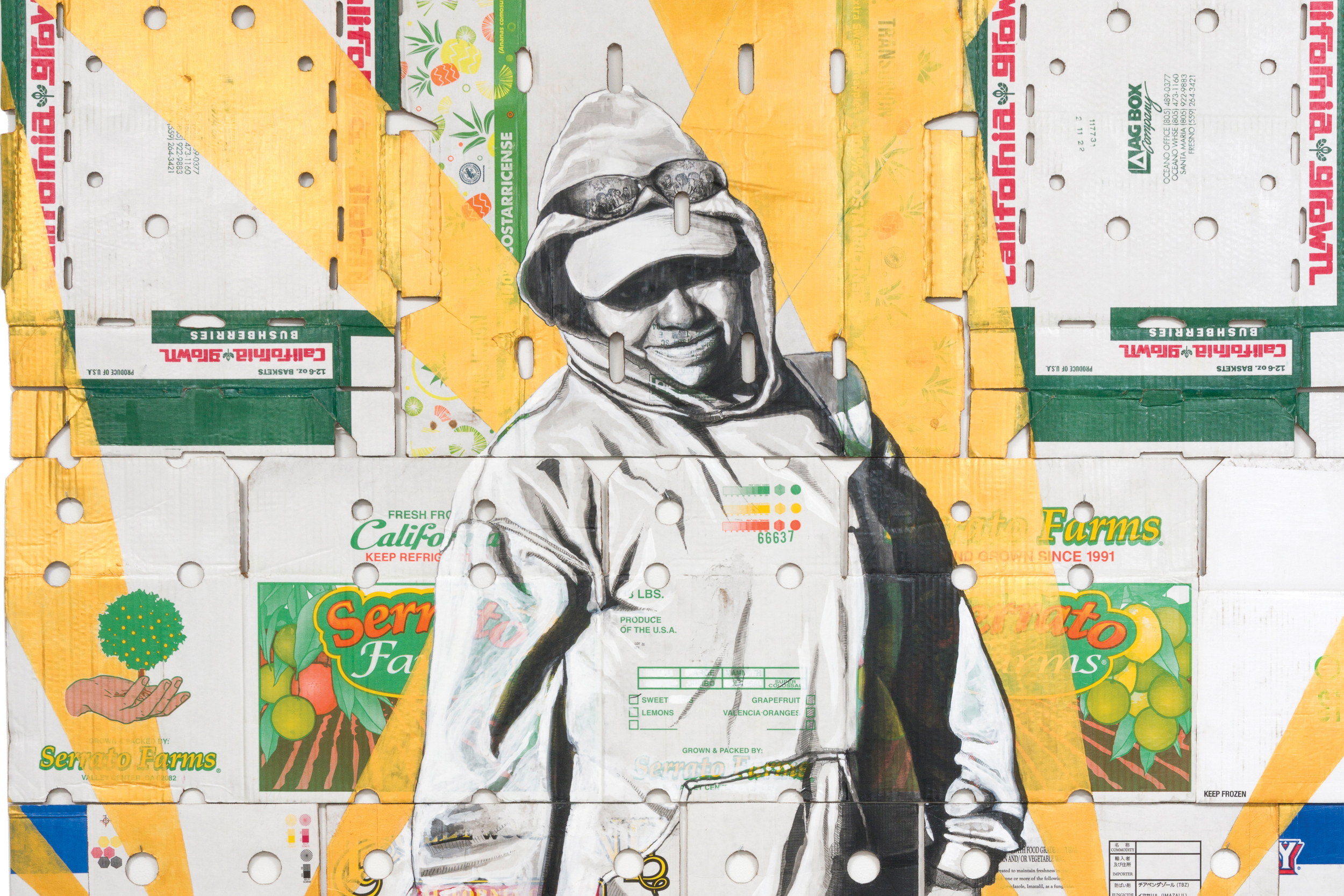

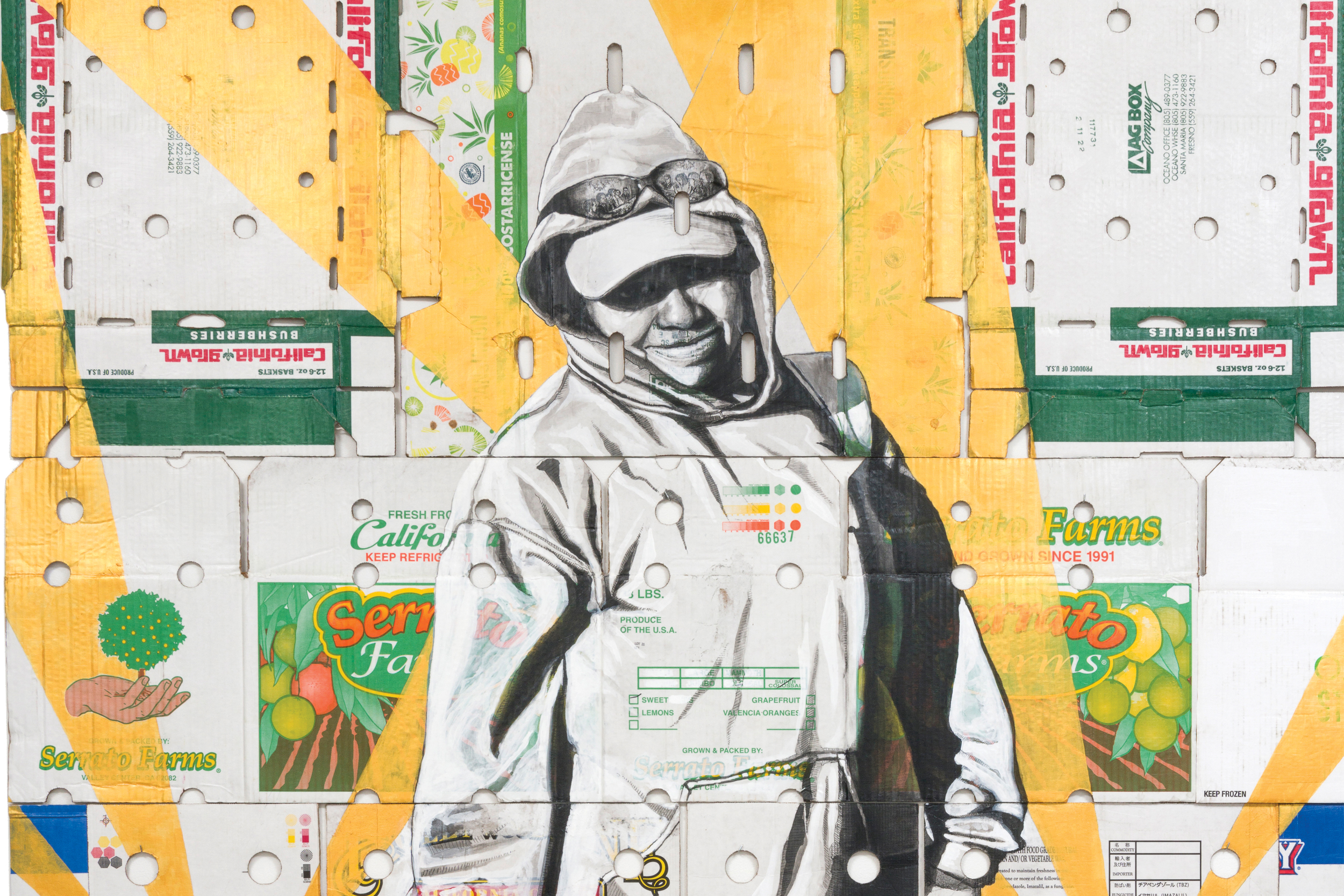

Martinez began incorporating discarded produce packing materials into his art around late 2016 or early 2017, a practice born from a confluence of personal experience and artistic necessity. While pursuing his undergraduate studies and subsequently between undergrad and graduate school, he spent three years working in the agricultural fields of Washington state, living with his sister. During this period, he utilized discarded produce boxes, often sourced from Costco, as a drawing surface for sketches and studies. Initially, he focused on the plain interior of the boxes, overlooking the printed labels and branding.

The pivotal shift occurred in 2015 when he returned to graduate school and found himself unable to continue with oil painting on canvas. A simple act of collecting a banana box from a Costco in Los Angeles and drawing a "banana man" on it sparked a new direction. This personal project, undertaken without a formal assignment, eventually led to a profound realization during a class critique. With the guidance of his peers and faculty committee, it became clear that his art was a vehicle to depict the working class, and more specifically, agribusiness and farmworkers, given the very materials he was using. This marked the genesis of his distinctive artistic approach.

Martinez’s personal history is deeply intertwined with the agricultural labor he portrays. He began working in the fields in 2009, shortly after transferring to Cal State Long Beach. Facing financial challenges with tuition, he joined his family, who were already engaged in farm labor. They provided him with housing and food, allowing him to save his earnings. He continued this demanding work through his undergraduate studies and for three full years, supplementing his income during summer breaks throughout his graduate program, accumulating approximately nine years of hands-on experience in the fields. This commitment involved traveling to Washington state at the end of each school year and returning just before classes resumed, maximizing his time and income.

His labor in the fields encompassed a variety of crops, beginning with asparagus, a particularly arduous task due to the constant bending and lack of shade. He also harvested cherries, various apple varieties such as Gala, Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, and Fuji, as well as peaches and blueberries. These direct experiences provided him with an intimate understanding of the physical toll and often challenging conditions faced by farmworkers.

The profound impact of these experiences fuels Martinez’s artistic mission. He explains his inherent shyness as a driving force behind his pursuit of art, a medium through which he can express ideas and shed light on overlooked realities. His work aims to raise awareness about the individuals behind food production, highlighting the contributions, presence, and humanity of farmworkers. He observes that farmworkers have historically been marginalized and neglected, both in the United States and globally. His overarching goal is to "dignify farmworkers."

The response from the farmworker community to his art has been deeply moving. Having worked alongside many of them, Martinez developed personal connections. He recalls farmworkers asking when he would draw them, indicating a desire to be seen and acknowledged. He believes that when individuals are taken into account, it fosters a sense of belonging, recognition of their contributions, and a feeling of being part of a community, akin to the pride he felt upon receiving his first identification card. He has organized exhibitions specifically for farmworkers, eliciting an overwhelming and emotional response, characterized by shared stories and a profound sense of validation. He hopes his art allows them to see themselves reflected and to understand the vital importance of their labor to the nation’s sustenance.

Martinez’s work directly addresses the power dynamics within the food system. He articulates that when he arrived in the United States with limited education, he observed a system that seemed designed to perpetuate the oppression of farmworkers. He notes the historical reliance on vulnerable communities to perform the essential task of harvesting the food that sustains society. The fact that these individuals, who are so critical to national well-being, have been denied a dignified existence is a source of profound sadness for him. He perceives farmworkers as having been politically exploited as scapegoats throughout history, lamenting that they have rarely experienced a dignified life. He expresses a hope that the public will advocate for legislation that promotes a more equitable and improved life for these essential workers.

A common misconception he aims to correct is the notion that farmworkers are merely laborers devoid of personal lives. He emphasizes that farmworkers are human beings with dreams, aspirations, struggles, and the full spectrum of human emotions—joy, sadness, and everything in between. He believes it is long overdue for this fundamental truth to be recognized.

Reflecting on the political climate, particularly actions targeting agricultural workers, Martinez finds the current situation deeply unjust. He expresses disbelief that individuals performing such vital work are being persecuted, deeming it unacceptable. He draws parallels to the historical United Farm Workers Movement, inspired by leaders like Larry Itliong, Cesar Chavez, and Dolores Huerta, who fought for a more dignified existence for farmworkers. He expresses gratitude for organizations dedicated to supporting farmworkers, educating them on how to protect themselves from deportation and other threats. The unsettling imagery of military presence in agricultural areas further underscores the harsh realities faced by these communities, which he believes are often manipulated for political gain.

The widespread recognition and inclusion of his work in major museum collections have been a significant and pleasant surprise for Martinez. He had not anticipated the extent to which his art, created by an Indigenous immigrant artist, would resonate with such diverse audiences, from fellow farmworkers to academics, researchers, and museum professionals. This broad appreciation underscores the universal human themes his art explores.

His initial impressions of the United States as a young immigrant were marked by culture shock, stemming from the dramatic differences in urban landscapes, transportation systems, and societal norms compared to his rural Oaxacan upbringing. Despite the initial adjustment period, he came to appreciate the diversity of cultures and cuisines available in the U.S. Learning English was a crucial step in navigating this new environment, empowering him to engage with educators who instilled confidence in his pursuit of higher education. This educational path provided him with a broader perspective, enabling him to understand his own cultural heritage and its place within a larger historical context. He recognizes the complex legacy of colonization and the ongoing struggle for equity faced by Indigenous peoples.

Martinez sees a strong connection between his current artistic practice and the rich sociopolitical and labor-focused art traditions of Mexico, particularly the muralist movement. He was profoundly influenced by Mexican muralists like David Alfaro Siqueiros during his studies. The concept of muralism, with its emphasis on collage and the unification of diverse elements on a grand scale, informs his larger works. He finds Siqueiros’s "América Tropicale" mural particularly impactful, resonating with his Zapoteca heritage and the depiction of struggle. He aspires to create art that similarly evokes powerful emotions and stimulates critical thinking in viewers.

Looking ahead, Martinez plans to expand his artistic scope to encompass the experiences of farmworkers globally. He recognizes that the struggle for fair labor practices is not confined to the United States, noting similar challenges in his home country of Oaxaca and in other nations with significant agricultural sectors. His future projects involve visiting and potentially working in orchards and fields in different countries to document and illustrate the shared experiences and common struggles of farmworkers worldwide, exploring the universal factors that perpetuate these challenges. He aims to draw connections between the plight of farmworkers in the U.S. and those in regions like Nicaragua or Colombia, seeking to understand the common threads that bind their experiences.