For generations, the phrase "time immemorial" has resonated within Indigenous communities and their advocacy, frequently appearing in journalism pertaining to Native affairs. While often serving as a succinct affirmation of Indigenous longevity on ancestral lands, its frequent use has occasionally led to it being perceived as a journalistic cliché. However, a deeper examination reveals that this seemingly simple phrase holds profound significance, directly challenging entrenched Western historical narratives about the peopling of the Americas and asserting Indigenous sovereignty rooted in an ancient, unbroken connection to the land. It represents a potent counter-narrative to colonial frameworks that have long sought to minimize or erase the deep history of Indigenous peoples.

The prevailing Western scientific consensus for decades posited that humans first arrived in North America approximately 12,000 to 13,000 years ago. This widely accepted narrative, known as the "Clovis-first" theory, suggested that early inhabitants migrated from Asia across a land bridge spanning the Bering Strait during the last ice age, subsequently spreading throughout the continent. The theory drew its name from distinctive fluted spearpoints discovered near Clovis, New Mexico, which became the diagnostic marker for the earliest human presence. This model, characterized by its perceived elegance and simplicity, gained canonical status in academic research, classrooms, and popular culture, offering a seemingly tidy explanation for human migration into the Western Hemisphere.

However, this narrative consistently diverged from the oral traditions and historical accounts preserved within Indigenous cultures, which speak of a much deeper, more ancient presence on the continent. Professor Philip J. Deloria, a Yankton Dakota descendant and historian at Harvard University, explains that "time immemorial" encompasses "the deepest possible kind of human memory, beyond recorded history, beyond oral tradition, beyond oral memory, into what we call the deep past." This Indigenous perspective directly confronted the colonial implications of the Clovis-first story, which, whether intentionally or not, often served to undermine the legitimacy of Indigenous land claims by portraying Native peoples as relatively recent arrivals, not fundamentally different from later European colonizers in their migratory patterns. This historical framing implicitly justified settler colonialism by suggesting that Indigenous peoples were merely another wave of migrants, stripping away the unique ancestral connection and inherent rights to the land.

The scientific establishment, in its adherence to the Clovis-first model, often vigorously suppressed or dismissed archaeological evidence that suggested an earlier human presence. This resistance created a significant barrier for researchers whose findings contradicted the prevailing paradigm. Dr. Paulette Steeves, a Cree-Métis archaeology professor at Algoma University and author of The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere, argues that academia actively ignored and marginalized evidence of pre-Clovis human habitation for over a century. Publishing such findings often constituted "career suicide" for archaeologists, leading many discoveries to be characterized as pseudoscience or simply to remain unpublished.

One of the most notable examples of this academic resistance is the Calico Early Man Site in California’s Mojave Desert. In the 1960s, world-renowned archaeologist Louis Leakey, celebrated for his discoveries of early hominids in Africa, uncovered what he interpreted as stone tools and flintknapping debris, dating back potentially tens or even hundreds of thousands of years. Despite Leakey’s immense stature, his findings at Calico were met with widespread skepticism and ridicule, damaging his professional reputation and hindering further investigation into potentially older sites. Critics often argued that the artifacts were geofacts, shaped by natural forces rather than human hands, a dismissal that persisted for decades.

Beyond Calico, numerous other archaeological sites across the Americas presented compelling, albeit contested, evidence of pre-Clovis habitation. The Monte Verde site in Chile, with its well-preserved organic materials, has yielded dates exceeding 14,500 years ago, pushing back the accepted timeline of human arrival in South America and consequently challenging the Beringian migration route as the sole pathway. In North America, sites like Cactus Hill in Virginia, dating back over 15,000 years, and the Gault site in Texas, also showing evidence of pre-Clovis human activity, contributed to a growing body of contradictory evidence. Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania provided artifacts suggesting human occupation up to 16,000 years ago. More recently, discoveries at Chiquihuite Cave in Mexico have indicated human activity potentially as far back as 26,000 to 30,000 years ago, while the Hueyatlaco site, also in Mexico, has controversially suggested dates possibly hundreds of thousands of years old, infuriating proponents of the colonial-minded narrative. The persistent dismissal of these findings, according to Steeves, reveals an "embedded racism" and bias within the scientific community, where robust critiques often precede formal publication of any evidence challenging the established timeline.

The tide began to turn with landmark discoveries that received institutional endorsement. In 2021, Science magazine published a report on 20,000-year-old human footprints discovered near White Sands, New Mexico. This unequivocal evidence of human presence during the Last Glacial Maximum marked a significant shift, signaling a broader acceptance within the scientific community that humans inhabited North America long before the Clovis era. The report’s authors explicitly stated, "These findings confirm the presence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum," effectively dismantling the long-held Clovis-first dogma and validating what Indigenous peoples had asserted all along.

Beyond archaeology, other scientific disciplines have also provided compelling support for a much deeper human history in the Americas. Linguists, studying the immense diversity and complexity of Indigenous language families across the continents, estimate that such linguistic differentiation would have required at least 30,000 years, if not more, to develop. Furthermore, DNA researchers have identified genetic links between some Indigenous South American populations and Austronesian peoples, suggesting ancient trans-Pacific migrations that bypass the Bering Strait entirely and point to multiple, earlier waves of arrival.

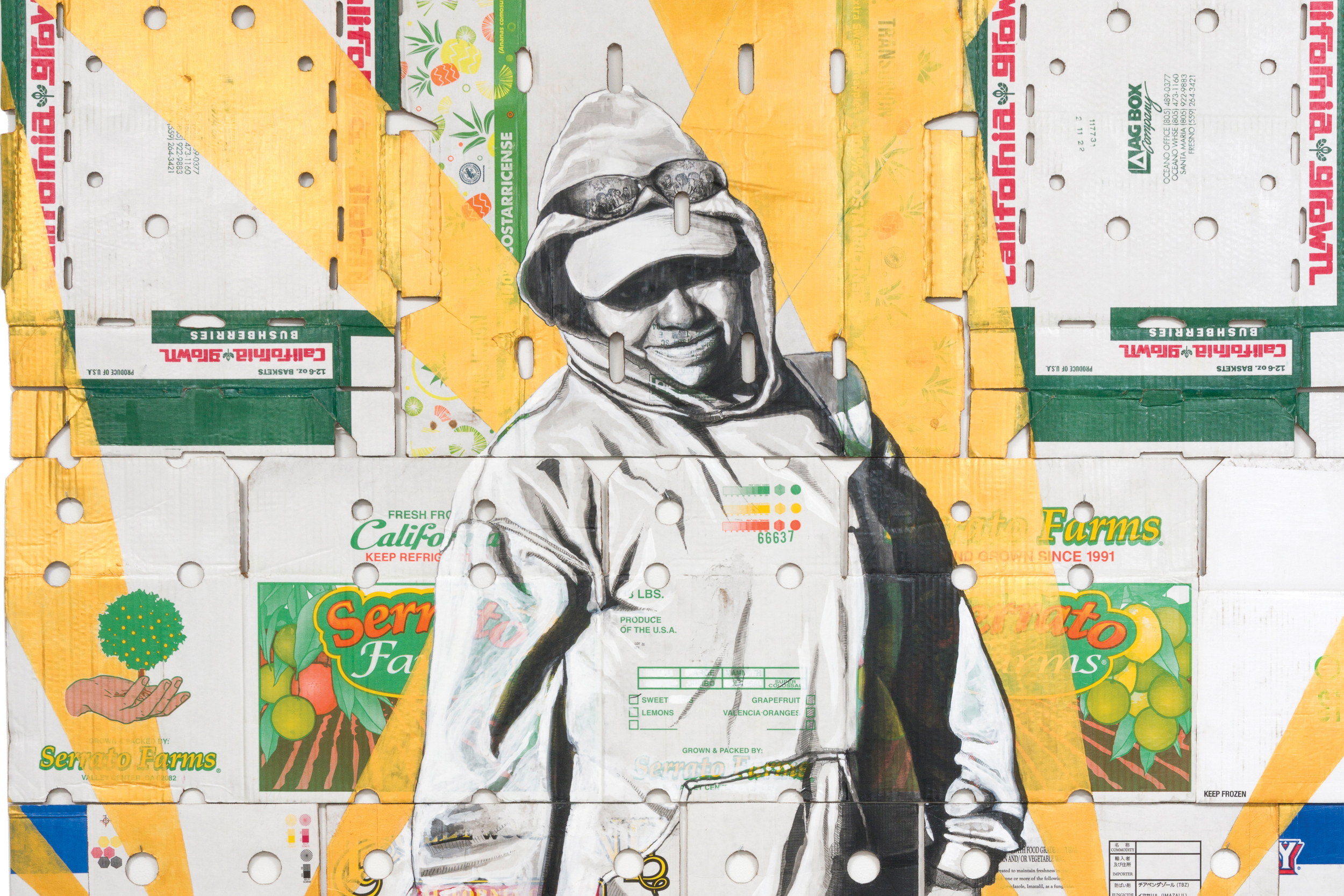

The rich tapestry of Indigenous oral histories, often dismissed by Western science for lacking written records, also finds powerful corroboration in the monumental physical evidence scattered across North America. These oral traditions, meticulously passed down through generations under the guidance of elders and imbued with a profound sense of community responsibility, are not mere legends but historical accounts of deep time. They speak of civilizations that flourished long before European contact, their legacies etched into the landscape. The weathered remains of the tamped-earth step-pyramids of Cahokia, near present-day St. Louis, once formed the heart of a vast Mississippian city with an estimated population of tens of thousands, rivaling contemporary European urban centers. Further south, Poverty Point in Louisiana showcases massive earthworks constructed around 1600-1000 BCE, indicating complex societal organization and engineering prowess. In the American Southwest, the Hohokam people developed an intricate network of hundreds of miles of agricultural irrigation canals along Arizona’s Salt River, a system that Popular Archaeology has noted "rivaled the ancient Roman aqueducts." In the Ohio River Valley, the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, a series of geometric earthen constructions aligned with solar and lunar cycles, demonstrate sophisticated astronomical knowledge and societal cooperation over vast distances.

Professor Deloria aptly refers to these as North American Classical civilizations. Yet, settler narratives have routinely omitted or downplayed their significance, denying North America a "classical period" comparable to those in Europe. While European Americans readily lionize Greek and Roman antecedents, similar recognition for Indigenous predecessors has been largely absent from mainstream education and popular imagination. The phrase "time immemorial" thus not only asserts longevity but also underscores the profound sophistication and cultural achievements of these ancient North American societies, demanding their rightful place in global history.

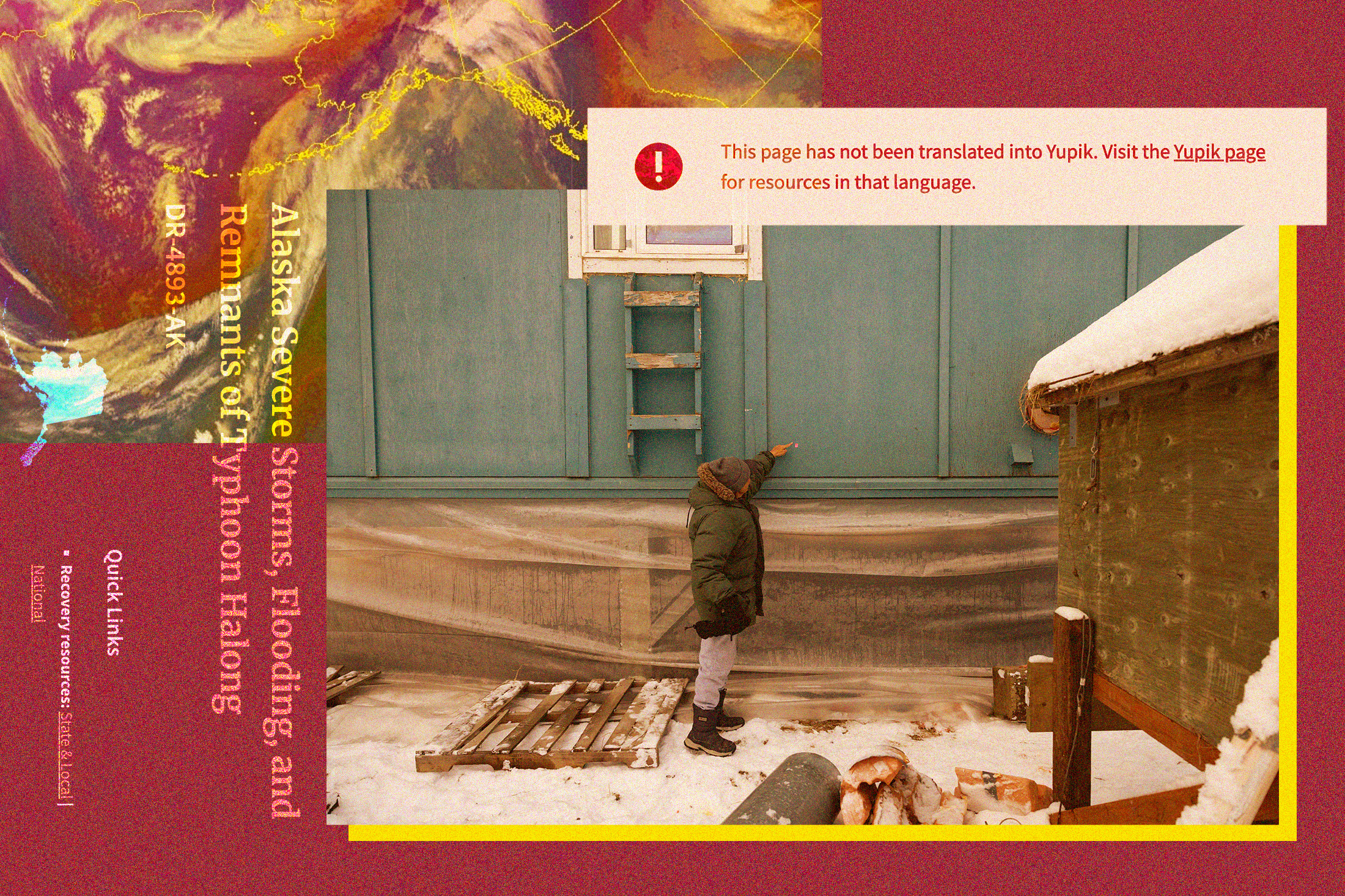

The re-evaluation of these deep time narratives carries profound implications for contemporary Indigenous rights, land claims, and the broader project of decolonization. By challenging the Clovis-first and Bering land bridge theories, the historical foundations of settler-colonialism begin to erode. The idea of a "New World" waiting to be discovered and settled collapses when confronted with evidence of vibrant, ancient civilizations. This historical re-framing directly undermines narratives of white supremacy and American exceptionalism, revealing a continent with a rich, complex past that predates and will outlast colonial constructs. The assertion of "time immemorial" transcends academic debates over precise dates, instead affirming an enduring cultural presence and inherent sovereignty. As Professor Steeves emphasizes, "It’s really important right now to decolonizing settler minds, to decolonizing education, and to decolonizing ourselves." For Indigenous peoples, "time immemorial" is not merely a historical marker; it is a declaration of identity, resilience, and a future deeply connected to an ancestral past that defies colonial attempts at erasure.